India's Union Of States: Asymmetric Federalism

Nikhil Sikka

27 Oct 2021 11:09 AM IST

"Federalism isn't about states' rights. It's about dividing power to better protect individual liberty."

- Elizabeth Price Foley, Professor and Legal Theorist.

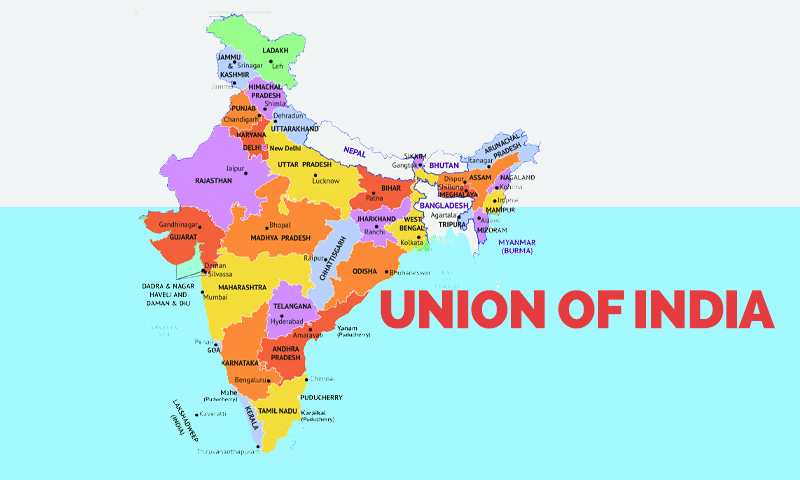

The Constitution of India describes India i.e., Bharat as a Union of States according to Article 1(1). Since its inception, diversity has been an important theme of the Indian constitution and believes in the underlying theme of 'unity' of people. The Drafting Committee of the Indian Constitution, laid emphasis on the term 'Union' as symbolic of the determination of the Assembly to maintain the unity of the country.[1]To further strengthen this unity, federal system of governance was opted by the committee as "Federalism offers a way for diverse communities to come together and derive the strength of unity while retaining their identity".[2] A federal nation is one with a combination of two levels of government i.e. the central and the state government, where there is a substantial division of powers among them and both share equal status in a single political system.

Charles Tarlton was the first one to introduce the concept of 'Asymmetric Federalism' in his article published in the Journal of Politics in 1965. In order to understand this, it is necessary to draw a distinction between de facto and de jure asymmetry. "The first refers to the type of asymmetry that is a feature of all federations to some degree, namely differences between subunits in terms of size and wealth, culture or language, and those differences in autonomy, representation and influence in the wider federation that result from such attribute".[3] Former is the one that existed in all the federations as it refers to the variance in the demographic and geographic sizes of the states and is also known as political asymmetry. The second type, also known as constitutional asymmetry, is evident in the design of the constitution itself as "it refers specifically to differences in the status or legislative and executive powers assigned by the constitution to the different regional unit"[4]. In other words, they made a conscious decision to give special status, powers and autonomy to some states but not extend it to all. Articles 370, 371 and the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act are perfect examples of this. Since the above-mentioned asymmetries exists in India, it is enough to construe that the Union of States in India is a precise demonstration of asymmetric federalism.

The asymmetries in India can be seen in various kinds. Firstly, representation in the Rajya Sabha is based on the population size of the state and not based on equality among them and due to low levels of population some Union Territories have no representation at all. Secondly, the differences in administration of tribal areas, inter-state administration and law and order of certain states. Third, some UT's like Delhi and Pondicherry enjoy special powers over others[5]. Fourthly, the greatest of all the asymmetries is by the provisions of Article 370 that provides J&K to have its own constitution and make its own laws and Article 371 which provide multiple other states such special powers.

Moreover, the difference between the USA (Symmetric Federalism) and Belgium (Asymmetric Federalism) can help us to further understand this asymmetry. There are some common and distinct features in Indian federalism as compared to the USA and Belgium[6]. Although asymmetric in nature, Belgium has maintained equality of powers among the centre and the state and the case is similar with the USA, where the states have equal authority to operate and no state is given special recognition, while in India few states are considered special as compared to others. Despite equal powers Belgium is asymmetric as it has given no power of secession to the states unlike USA. As power division is of essence for federalism, USA's governance system is divided into centre and state government, Belgium has one more level community government which is like the local government (or panchayats) in India. Although this third branch doesn't have official recognition, they get their powers from the constitution itself. USA follows Presidential form of government, where President is the head of the state while in Belgium and India the Prime Minister and its cabinet ministers have the real power as they follow Parliamentary form of government. Moreover, in India a Governor has the akin powers to operate the state as the President has for the country, the constitution takes that power away from the state and gives it to the centre[7] in certain situations leading to unequal power distribution. Hence, India being a democratic and federal country, there are asymmetries in its federalism.

"The significant erosion of the autonomy enshrined in Article 370 since 1953, as well as the rise of a militant separatist movement in the Kashmir Valley in the late 1980s, should give us a pause to question the success of asymmetrical federalism in managing minority nationalist conflict in India".[8] Those in favour of the asymmetry take the moral high ground and argue that individuals are different and have different needs and federalism is about individuals and not about the states. But this is not at all true as it clashes with the essential part of federalism: protection of equality among individuals and would lead to the creation of two classes among the citizens[9]. The functional arguments in its favour are that constitutional symmetry and equal representation as features of federal system are misleading and asymmetry is required to hold together the states as one and for the long-term survival of the federations.[10] Tarlton argued against the presence of such constitutional designs in any federation due to its naturally high variation of interests among federal sub-units, because of the prospect that such designs would surge secession potential.[11] In the words of Rainer Bauboeck the "glue that can maintain federal cohesion in multinational democracies is not a shared national identity, but a shared conception of federal citizenship"[12]. Rather than promoting these differences emphasis should be on a way to give recognition to these asymmetries and work in the direction to get away with it rather creating asymmetrical power structure that further leads to more asymmetries.

"Dr. Ambedkar, one of the principal architects of our Constitution, considered our Constitution to be both unitary as well as federal according to the requirements of time and circumstances."[13] But the federal powers are asymmetric in nature with India being replete with both political and constitutional asymmetries. India, Belgium and Canada are reasonably well-functioning example of such democracies[14] but, they haven't been developing as much as symmetric federal democratic countries like the USA and Australia. For India to make full use of its actual potential, the discriminations must be removed and sorting out the governance system would help as this asymmetry actually leads to division and separation among people. The decision on revocation of Article 370, providing special status to Jammu and Kashmir, has passed the test of judicial review and this could be considered as the first step towards streamlining of the powers of the states and shifting from asymmetric to symmetric federal system of governance in India. But there is a long way to go in order to achieve the symmetries.

The author is a student at Jindal Global Law School.Views are personal.

[1] Hinsa Virodhak Sangh v. Mirzapur Moti Kuresh Jamat and Ors., A.I.R. 2008 S.C. 1892 (India).

[2] Amaresh Bagchi, Rethinking Federalism: Changing Power Relations Between the Center and the States, 33 Oxford Journal 21, 21 (2003).

[3] Louise Tillin, United in Diversity? Asymmetry in Indian Federalism, 37 Oxford Journal 45, 48 (2007).

[4] Rekha Saxena, Is India a Case of Asymmetrical Federalism?, 47 Economic and Political Weekly 70, 71 (2012).

[5] INDIA CONST. art. 240, cl. 2.

[6] Wilfried Swenden, Asymmetric Federalism and Coalition-Making in Belgium, 32 Oxford Journal 67, (2002).

[7] INDIA CONST. art 356.

[8] Tillin, supra note 3, at 47.

[9] Brian Barry, Culture and Equality: An Egalitarian Critique of Multiculturalism 312 (Harvard University Press) (2001).

[10] Tillin, supra note 8, at 50.

[11] Charles Tarlton, Symmetry and Asymmetry as Elements of Federalism: A Theoretical Speculation, 27 Journal of Politics 861, 866(1965).

[12] Tillin, supra note 10, at 50.

[13] State of Rajasthan v. Union of India and Ors., (1977) 3 SCC 592.

[14] Saxena, supra note 4, at 71.