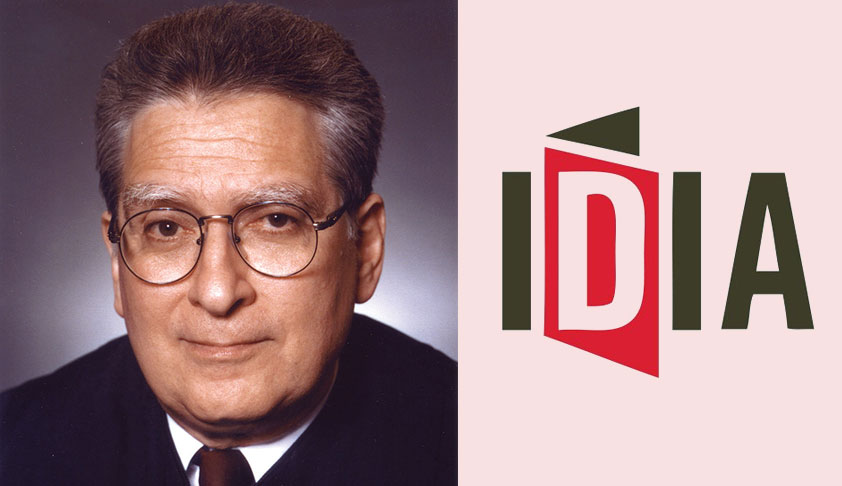

IDAP Interview Series: Interview With Judge Ronald M. Gould

LIVELAW NEWS NETWORK

4 May 2018 12:51 PM IST

Judge Ronald M. Gould, who has served on the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit with distinction since his appointment by President Bill Clinton in 1999. Judge Gould, an alumnus of the University of Michigan Law School, was diagnosed with a progressive form of multiple sclerosis in 1990. While the impact of his disability was initially confined to facing occasional stumbles and numbness in other extremities, his disability has now progressed to a point where he uses a power wheelchair, has no hand mobility and is supported by caregivers around the clock.

As Judge Gould's disability has progressed over the years, so has his perseverance, grit and resolve to not let his disability shape the course of his life. In his long and illustrious career on the bench, Judge Gould has developed a distinct voice as a judge and has adjudicated upon such hot-button disputes as the Trump travel ban.

Judge Gould's deep understanding of the challenges faced by the disabled has also found expression in his progressive verdicts on disability issues, that have helped breathe life into the rights legally guaranteed to the disabled in the United States. For instance, in a 2017 verdict on the rights of deaf inmates to access the services of American Sign Language (ASL) Interpreters, Judge Gould wrote: "To deny a deaf person an ASL interpreter, when ASL is their primary language, is akin to denying a Spanish interpreter to a person who speaks Spanish as their primary language… the County may not turn a blind eye to a deaf ear."

In this interview, among other things, Judge Gould shares with us the reasons why he is a great believer in the value gained by the disabled, of keeping a positive attitude and in focusing on what they can do as opposed to what they cannot. While acknowledging the enormity of the challenges faced by the disabled, he explains how they can be addressed by using proper techniques, methods and technology.

This interview was conducted on March 19th, 2018 by Rahul Bajaj and Maggie Huang. With the assistance of Judge Gould, this interview was also lightly edited for clarity. A recording of this interview can also be accessed in the link below.

Thank you so much for being here with us today Judge Gould, we really appreciate you taking the time to share your insights. First off, would you mind describing to us the precise nature of your disability?

Yes I'd be happy to do that. I have a pretty severe case of multiple sclerosis, which is a progressive disease where the nerves are attacked. There are different types of MS. I have a type called progressive, which can get very serious, and has progressed quite a distance. I use a power wheelchair to get around both my house and in my judicial chambers. I also have no hand mobility for the past several years, although I did have my use of hands when I first went on the bench.

I used to drive the wheelchair myself, but because I don't have hand mobility now, I have 24 hour caregiver help, 7 days a week. I have one sitting here with me today in Chambers.

I was diagnosed with MS in the 1990s, with a very minor disability. For e.g. I had an occasional stumble, I had numbness in other extremities, but that progressed to where I had to use a cane in the mid-1990s. When that progressed, I had to use 2 canes. Then finally starting in 1997, I had to use a power wheelchair. Note that at that time, I could still use my hands, I could control the wheelchair myself, and I was in law practise in my wheelchair. At the time, I had my hearing before the US Senate Judiciary Committee which gave a positive recommendation. Then finally confirmation to be a federal circuit judge in late 1999.

When I started off here in the chambers, I had only a need for occasional caregivers to visit me sometimes during the day, to drive me here in the morning and drive me home in the evening. That progressed as my disability progressed. So I shifted to 24 hour care, and to the idea of a caregiver in my chambers throughout the whole day in case I needed help. And that became what I had to do after my hand stopped working properly. I do have a personal assistant court staff. She helps me with typing emails, writing things, and reading communications, turning pages so I can read memos, or case opinions, etc. The Administrative Office of the US Courts provides me with an assistant to help on work matters because of my disability. But they don't want the person to be providing help on personal matters. So I have a personal caregiver, who for example, can hand me some water as we're talking because I have some problems with my vocal chords. That's the nature of the disability.

Thank you so much for a such detailed description of your disability, and how you work. You've reached what some would argue to be one of the most esteemed positions in the legal community — a judge at the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, before which you clerked on the US Supreme Court. You were in private practise, and even held positions as trustees of colleges and various organisations working on community issues. There are two parts of this question that we have. Firstly, as a starting point, do you mind explaining to our non-legal readers, especially in India, where the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit is in the judicial hierarchy of the US, and where exactly it is?

Yes, I'd be happy to do that. The United States is like India in this respect. It has a federal system. We have several governments – the United States national government, as well as governments in separate states. The US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, is one of the intermediate federal courts of appeals in the United States. The United States Constitution Article III establishes the power of the court, which in that document is the Supreme Court, to handle cases and controversies. Early in the history of the US, laws were passed that let the congress establish what are called 'inferior courts'.

Inferior courts are the district courts that hold trials, and have jurisdiction with several states matters, and also an intermediate court of appeals. So, the Ninth Circuit covers the states of Alaska, Washington, Oregon, California, Arizona, Nevada, Idaho, Montana, Hawaii, and also certain Pacific Island territories like Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands. These states are divided into several districts which roughly correspond with the geographic areas. There is at least one federal district in each state, sometimes more, if they have more than one representative in the U.S. House of Representatives based on population. But, describing the district courts — The intermediary court of appeal is handled by the Circuit Courts of Appeal. And you have 12 circuit courts in different state boundaries, and the District of Columbia Circuit. And we have a Federal Circuit, specialised in appeals on a few subject matters.

The second part of our question is – can you describe to us why you decided to study law first of all, and why you decided to become a judge as opposed to the other paths that were available to you? So can you comment to us on what led to your inclination towards the judiciary?

I did not have an interest in being a lawyer or judge in high school. I'm sure I didn't even really know what lawyers or judges did in those days. I went to college at a business school, the University of Pennsylvania at the Wharton School of Commerce and Finance. In my 4th year there, I decided I wanted to go to graduate school, and started thinking about that. Just by coincidence or happenstance, one of my college roommates was going to apply to law school. His father was a lawyer and had been at University of Michigan Law School, and thought I should consider that. So I decided to consider it. The more I looked at it the more I thought it would be challenging and I would like it. So I applied and they accepted me and I decided to attend.

I took a couple of years off after graduating college for family matters. But then I started law school in the summer of 1970. I'm happy to say I did very well in law school. The academic success opened up other opportunities for me, such as clerking. I clerked for Judge Wade McCree on the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, which was like the Ninth Circuit but covered other states — Michigan, Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee After that I clerked for Justice Potter Stewart of the United States Supreme Court.

I ended up deciding to be a judge when the opportunity arose, which I hadn't really been seeking. I loved practising law. I practised law for 25 years in Seattle. I had good clients, and a supportive law firm. I enjoyed myself. One day when I was taking a deposition in Alaska, a receptionist came into the conference room and said "I have a phone call." I said "I can't take the call, I'm busy I've got a deposition." She said "Well you might want to take this one, it's from the White House." All the other lawyers told me I should take the call. So I took the call and one thing led to another, and finally I was selected to be a federal judge.

Wow thank you, that's sounds like a very exciting day. If we could backtrack a little bit before that call and that day. Could you tell us a little bit about when you first received your diagnosis of MS? Can you share with our readers for background, how this initially impacted your life, and your foreseeable career path?

Yes certainly. I joined my law firm in December 1975. I was practising law at Perkins Coie — an excellent firm in Seattle, and stayed with that firm without exception or departure until I left Perkins Coie to become a judge. I did teach at the University of Washington Law School a bit on an adjunct basis. When the MS rose up, it was like a problem that came up out of the blue. I had some numbness in my fingers, and hands. I went to the hospital and saw a doctor. They weren't sure what it was. They ended up telling me it was most likely MS, but there was potentially a different diagnosis, though they thought that MS was most likely. And it turned out it was.

At first, MS had no impact on my home or work life. It wasn't any problem at all in the start. It was just a little numbness. Then it went from that to having the occasional stumble or trip and fall, because my foot would drag. And I just continued on with work, and my home life.

By about the mid-1990s, about the time I had become President of the Washington State Bar Association, I was walking with two canes. But that didn't stop me from practising, and really shouldn't stop anybody. It had no effect on my personal life that was significant. I traveled with my wife and children doing the kinds of things families do. The first time I noticed an unusual problem was when my wife and kids were with me on vacation. We were touring in Italy in an area that was very hot. And because my MS was what they call heat sensitive, I experienced for the first time in my life, a situation where all of a sudden I had trouble walking, and I had to sit down because I got overheated. So that's the kind of thing that would happen.

On business matters, for my law firm, this was never a problem in the 1990s. I could get around easily — and then zoom around in my wheelchair starting in 1997. And before that I walked around with my cane. There was a problem that I'll mention; there was a business trip that indicated some of the uncertainties of MS. I was in New York on a business trip, I had a trip and fall in my hotel room, but then I was unable to rise to my feet. Luckily I could reach the phone, I called the front desk. They got help to my room, a very strong man lifted me up. I'm sure no one in my law firm, or anyone in my family ever heard of that incident. So, unexpected things could happen, but they're not a reason to change course.

And as for the impact on my practise, I suspect that some of my law firm partners were curious or wondering what was the problem that made me walk with a limp or with a cane. But in fact, no one ever asked me questions. And I did not volunteer that I had MS at that time, because of a concern that it might hurt my career, make it harder for clients to be referred to me and so on. But that's basically the situation in practise.

By that time, the tentative diagnosis of MS had been definitely confirmed by more advanced medical science, such as the use of an MRI. Of course, my wife and my family knew. I think my children knew as well. They knew that I had MS but I still saw no reason to disclose a medical diagnosis to business clients, or even to the partners in my law firm at that time. And because the disability was not affecting my work, I was still handling a lot of client business, and I was still developing new clients, so no questions ever came up with my partners. And I never asked for any accommodations at all. Because none was needed at that time. The only personal accommodation I used was that I made sure I got a disabled parking permit, so I could park near the garage and near the elevator in the garage. It was quite different by the time I became a judge.

We would love to hear about that in response to our next question, but before that, I would like to ask one follow up about something you said in response to these questions. You were slightly hesitant about disclosing your disability because of the thought that it might adversely impact your growth prospects professionally. Do you think that was more a function of an inhibition that you had, or something that could genuinely impact your growth prospects? Do you think this is something that continues to hold? That if you do have a disability, it might impact your growth prospects adversely?

That's an excellent question. I would never know for sure if it would have had an impact. I don't remember the exact year when the Americans With Disabilities Act was passed.

1990

1990 okay. At the time, when I was first diagnosed, it perhaps hadn't yet been passed; but it wasn't yet in the consciousness of me or businesses like my law firm. So once that law was passed, and similar state laws, I think people wouldn't have to worry about the disability, and losing their job. At the time when it first came up for me, I wasn't sure.

A related point, and you'll understand this from your law firm practise, is that in the United States at least, in big law firms, the progress a person would be able to make professionally and financially was dependent in part on attracting new clients, on being able to handle something referred to you from another client or from another lawyer in the firm. So I really wasn't sure even at that stage where I had a good track record, whether disclosing disability would have decreased my ability to develop work, or get work from my partners.

You were in private practise as you mentioned, at the law firm that you joined in 1975, when you were diagnosed with MS, and then after which you became a judge. You already spoke about some of these, but can you tell us what kind of concrete accommodations you required, and more broadly, have you noticed in your career any pertinent differences between being in private practise, and being in the judiciary, as someone with a disability? And have you found one professional path more accessible than the other?

That's a very good question. As I said, I didn't really need much accommodation in law practise, so I can't say for sure how the private firms are dealing with that these days, although I certainly see some cases brought by people with disabilities. And they sometimes are not happy with the ways their employer has accommodated them. So I know there's some of that. On the other hand, as part of the judiciary, I've been very fortunate that the court itself has been supportive of everything I've been trying to do. And I think accommodations are a challenging subject with a progressive disease, because it's not a situation where something is set and fixed, and you can accommodate it, and then you're fine from there, because it can change or get worse.

But still from a point of view from a disabled person, the thing to do is to be positive. So to give an example, I was walking with a cane at the time I was going for my interview with the White House about getting my judgeship. And I slipped and fell right on Pennsylvania Ave, about a block from the White House entrance. And I just had to get up, brush myself off, and keep going. A disabled person should, if they have a problem, react to solve it, and keep going and persevere. Now in terms of actual accommodations I've got in my job – there are so many I'm not sure I can describe them all, but let me tell you what was most important.

From the outset of my court service, it was necessary for me to come from home, from the suburbs of Seattle, down to downtown Seattle where the courthouse is to work. And to do that, I had to come to Chambers in a special travel van that would accommodate a wheelchair. I had a ramp to get in and out.

To get into my building and chambers, it required going through several levels of doors, certain parts of security in the courthouse. What the court did for me which I really appreciated was, they set up all the doors that I had to traverse, like a path from the garage up to my chambers, with little electric motors that would open the door at the press of a button. For me, because I couldn't necessarily reach the buttons on the wall for regular people, they would give me an electronic device on my keychain, I had four buttons on that little keychain. One would open a door to my secure area, a second one would open a door into my chambers itself, a third one inside the chambers into my office, and a 4th one would open doors to other areas in the chambers.

And, that was just to get here, in Seattle. The Ninth Circuit sits in lots of other cities. For the first 6 or 7 years of my judging career, I traveled to hearings in other areas. I had to travel to San Francisco, and to Pasadena which is outside of Los Angeles. And California, Portland. Of course I had to use accommodations. To do that I had to first take my van out to the airport, then use special procedures that the airlines had, to get a disabled person on an airplane. Those weren't too complicated, they just had to go through the right procedure that would lift me out of my wheelchair, and put me in an aisle chair that was used to get me to my seat in the airplane.

And then in the other cities I went to, I had to arrange to rent a van like the kind I used to get from the airport to my hotel. And of course I could use my own van to go somewhere close like Portland, but I couldn't go to hearings in Pasadena, or San Francisco, it was a very long drive which I didn't want to do at the time. So in those cities I would fly there, and then I'd rent a van. And I could get from the airport to the hotel. I used a lot of specialised equipment. Like for example I can't transfer safely from my bed to my wheelchair, so I use a lift. While I could take my lift to support myself in Portland, in Los Angeles and San Francisco, I bought a couple of extra lifts and the court agreed to store them in the courthouses there.

There was a similar situation with the shower chair. I brought extras, which the courthouses stored. So I could travel to another city, use a rented van to get to my hotel, and I could pick up my special equipment there, I could pick them up at the hotel, and be able to get everything done. So that's how I traveled.

The next major accommodation was, that I started to use voice recognition software. I used this not only as a judge in the courthouse, but also at home. I point out a couple of other things that helped me in that respect. [The court] got the most updated version of the software that I use. Secondly, the court also makes sure I.T. people visit my house, and gave me programs to use in my home computer, so I could get documents efficiently sent to me at home, or sent from my home to my office.

Another accommodation is that, my personal caregivers come to my chambers to assist me on personal matters. And another big accommodation, is that the Administrative Office of the US Courts has provided a personal assistant to assist on work matters, but not personal matters. And so that's been a big help.

And of course the I.T. people are invaluable in letting me get my work done because these days, there's a lot of assistive technology available in software, so I would encourage any disabled person to make the most of the assistive technologies available.

So about mid-2007 period, I had to stop traveling for health reasons. All of the hearings and meetings that are not in Seattle are handled by me with video conference. For some meetings, I can do this by phone. But all hearings in court except those in Seattle are done by video conference. And there again, the court has an excellent I.T. staff, and they make sure that these devices will work properly. So when I get to the court room to sit in other cities, I appear there on the video screen that's set up. A couple of screens are set up. One is facing the advocate, just as if I was I was in the courtroom. And the other is facing the two judges I'm sitting with. And I go into my library; we have the device in there. That works extremely well. It would not work well without supportive staff, and the support that the court offers.

That was a very detailed and comprehensive response to thank you for that. Just one follow up – do you think that all these accommodations that have been made available to you are perhaps premised on the idea that, with these accommodations, you can function as effectively as your able-bodied counterpart? Now in India, the problem that we encounter often, is that this is not the premise that informs the way that people with disability in the legal profession are treated. So would you say, it's important for us to move to a place where, rather than this being done out of the goodness of one's heart, it is a matter of entitlement?

My personal view is that the law has a major role to play. The law has a role to play both in legislatures to pass statutes, and in the courts which should interpret those in a fair way. I think every disabled person should have a right to be given reasonable accommodations that permit them to work at the highest level. Of course there's a question of what's reasonable; and that's where the lines will be drawn. That should be a matter of right and not out of the goodness of somebody's heart. In my opinion, we also have the Americans With Disabilities Act on a federal and national basis. We also have counterpart state legislation. Every state, if they want, can give more protection than the federal law gives.

Unfortunately I didn't have time to do some extra homework to find out about India's disability law at present, but I would encourage people like you to do what you can to get the national government to pass laws at the federal level, like the Americans With Disabilities Act. And also because you have a federal system with different states with major areas. In large populations, people should consider working to get laws passed at the state level as well. That would be my thought.

I probably can't think of every single accommodation that's helped me to do what I do, but that probably covers the major ones. And getting the law to establish ground rules for employers, or for federal agencies would be a positive step.

In your contribution to the Pathways to the Bench series, you mentioned that initially you harboured a considerable amount of fear and anxiety about your ability to function effectively despite your disability. A lot of people with disabilities tend to internalize the lowered expectation that the society has from the disabled and tend to act in consonance with such lowered expectations. How did you deal with the feeling of self-doubt, and would you say that it has now completely gone away?

In practise, I didn't have a good deal of self-doubt, because I knew I could keep up with my work demands. And I was getting concerned about how clients perceived the disability. In the case that was mentioned on the Pathways to the Bench series – part of the reason why I was concerned at the one case was that at the time the Assistant General counsel hired me to handle a multi-million dollar litigation, I was walking with a cane. A couple of years later, when I was going to San Francisco for a deposition, at that point I was in a wheelchair. My situation had changed. That particular client put my mind to ease by telling me not to worry, no problem, they didn't hire me to run the 440. The 440 is a foot race, it's about 440 yards, about a quarter mile. It's often referred to in college/ high school athletics.

I've never really had a problem with clients once I was in the wheelchair. Maybe because they didn't want to say anything, to confront me, or they didn't care. I think it's a more common business attitude. The clients aren't going to care if you're getting the work done properly. I did gather a couple situations in my practise that I could not do in a wheelchair. So to give you one example, I was hired to handle a major lawsuit for a company that had a plant in a remote part of the United States, and there were no roads to that place. And, we couldn't get there by boat either. The only way to get there was to fly there in a small aviation aircraft, which would land at a landing strip that they made in that place. I could handle that if I was walking with a cane, but if I was in a power wheelchair at that time I could not have done it. The airplane would not have accommodated this. And I would not have been able to accommodate that work. That kind of situation is rare, where a person with a disability needs to recognise if something would be affected by it. But this should be the test, if a person can't do the work with the accommodation, then they can't do it. But almost everything can be done with proper accommodation.

The other problem I remember from practise — could be described this way. This was not a physical barrier, could be attitudinal. I had a big case where my particular client was a subsidiary corporation of a large international business. A large business had hired me, but I had to work with the local subsidiary which had an office in Seattle. That office was just in a small building that did not have elevators. In fact, the president of the company had an office up on the second floor which you could only get up to by walking up a narrow staircase. So I was able to do that when I first met the client. But throughout I started using my power wheelchair, I could not have gotten up to visit that person there.

The president of that company kindly agreed to meet me at my office, after I couldn't climb the steps at his. But the fact is that most company presidents aren't going to go to the lawyers' office. They're going to expect the lawyer goes to their office so they don't lose time. So once I was in a wheelchair, I'm sure I would not have landed that client to represent. But despite those limitations, those two that come to my mind, I'm very confident that situations like that are actually very rare, and that they will come up rarely in private practise. Most businesses can be visited by people in wheelchairs, and most clients can be visited without flying to remote landing strips. So I think people in wheelchairs, or people who are deaf, or who are blind, or have other disabilities, should just figure out what accommodation will let them do the work, then get the accommodations, and get the work. That's my thought.

Your disability began taking root at a time when you were an accomplished legal professional and not in the infancy of your career. In this sense, it was perhaps easier for those around you to accept your disability, given that you had already demonstrated your competence. Would you say that it would be much harder for a younger legal professional with a disability to gain acceptance, and, if so, how can they ensure that their disability does not become their defining attribute?

That's a good question. I don't doubt that I was fortunate to have established myself before my disability became so pronounced and obvious. It would be a bit more challenging for someone in a wheelchair or other disability to establish themselves starting from having a disability. But it can be done. When in law practice, I was still walking with two canes. In the mid-1990s, I got to be president of the Bar Association. I did some of my best and most important cases then. I was able to do my work well, with the exception of the two examples I gave you – being able to navigate a remote landing strip with a power wheelchair and, second, having a client who at the outset would not have wanted to come to Seattle to meet me, if I couldn't get to his office. Beginning lawyers with disabilities can do their job excellently, in terms of obtaining victories in court and getting more clients. I speak from experience, as I have hired disabled law clerks. They did a good job in law school before I hired them and have done a good job after leaving me. One of my former disabled law clerks is a private lawyer at a firm. He has been part of several multi-million dollar recoveries in litigation and became a manager at his firm. Another is an Assistant United States Attorney which is a very difficult job to get and perform. He does it excellently. Another disabled law clerk that I had worked at my former law firm for a while and then decided that she had made enough money and went to India. She is of Indian heritage and started an initiative called the Orphanage Project there.

You mentioned in the ABA interview that your client had no difficulty accepting the fact that you had a disability, as they said that they had not hired you to run a race. While this is very heartening, unfortunately, not all clients and employers think this way. If they had instead told you that they were skeptical about how you would go to court or cope up with the fast-paced manner in which a litigator has to operate, how would you have responded?

I can imagine that as being a possibility. If such a statement of skepticism had been made, I would have said that there is no basis for their concern. I was in a position to work in a fast-paced manner. My wheelchair didn't stop me from reading cases, from writing, from doing hard thinking about their cases. I would have further pointed out that in practise, for private firms, and it's true for government too, results are what count. I could get the results that they wanted. That's what I think I would have said, something like that.

A lot of employers agree with the need to embrace the diversity that a disabled professional brings to the table in the abstract, but fail to stay true to that principle in concrete circumstances. For instance, when tight timelines have to be met and key deliverables have to be produced, employers tend to choose able-bodied employees over their disabled counterparts as they can do the job quicker. There is, therefore, a fundamental disconnect between what I would characterize as the Friday evening view of accessibility versus the Monday morning view of accessibility. What steps can be taken to ensure that accessibility and reasonable accommodation do not get sacrificed at the altar of efficiency and productivity?

I think that's a tough question because maybe some employers think that way. It may not be the exact answer to give, but I'd say, in general, employers and clients have a right to expect work to be done at a pace commensurate with their needs. For instance, if a law firm expects a partner/associate to draft a reply to a motion for a temporary restraining order filed on a Friday and slated to come up to be decided on Monday, the lawyer should be able to do the job. However, that doesn't stop disabled lawyers from explaining how, with reasonable and proper accommodation, they can get the job done. If India doesn't have a law requiring that, you should get it passed at the national level. Further, you should try to get separate states to protect everyone in that state by enacting their own laws. In the US, the Americans with Disabilities Act and some other federal laws give rights to the disabled. However, nothing precludes the states from passing their own laws with higher or comparable standards. While I am not well versed in Indian politics, culture or law, my general understanding is that you have a federal system.

Follow-up: We do have a disability rights law, called the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, passed in 2016. However, the difficulty with using the law in such circumstances often is that you come across as being confrontational and standoffish if you use the law in such negotiations. As a result, it is received wisdom that one should try finding solutions outside the legal system.

I think that's a fair question. For instance, our ADA has been enacted for a very long time. Still there are employers who don't live up to their obligations on their job and don't make the accommodation that they should make which results in litigation. That's what the independent courts are for. The reality is that the challenges that the disabled face can be best met when there is a high level of public understanding and public education about what the disabled can do with proper and reasonable accommodation. The law can play an important role in setting expectations of people including employers, city planners, etc. about reasonable accommodation.

In a number of interviews, you have said that most people have to deal with significant problems in life – the only difference in your situation is that your challenges are more visible than those of others. Some argue that this narrative is flawed for two reasons. First, it makes light of the significant impediments that one has to face on account of a limiting disability by situating them on the same footing as the impediments routinely faced by the able-bodied. Second, since a large portion of the challenges that the able-bodied face are of a transient and reversible nature, inasmuch as they can be addressed with the right amount of effort, they are not an appropriate comparator for the challenges that the disabled face. This is because a disability is a permanent and irreversible condition. How would you respond to these two arguments?

I'd be happy to respond. First of all, you may have misunderstood the import of my comments in my ABA interview. It is true that the disabled face a lot of problems, and I am not in any way suggesting equivalence of problems between the problems faced by someone with a severe disability on the one hand and the life problems faced by the able-bodied on the other. To illustrate, someone who can't see, hear or walk obviously has a much tougher set of problems to face than the average able-bodied person who can do all that but has to face life problems. Despite that point which I think is a truism, I think it is a very valuable technique for the disabled to keep in mind that all people have problems which, though not visible, can be very disabling. As an example, we adjudicate upon social security cases. The litigants who appear before us sometimes have a disability flowing from a visible impairment but, other times, it is just as real in impact even when it arises from other mental limitations. This covers such extreme things like mental illness or, in the less extreme, something like personality disorders. For instance, if a person can talk and walk intelligently but has an unmanageable anger problem, they are not qualified to work in a position where they have to interact with the public. Others have a problem where they can't interact with a supervisor, so they can't hold a job. So it would be fruitful for the disabled to remember that, while they have an extremely severe disability, everyone else, including those helping them, can have several problems at a given point in time. Having said that, I am of course not negating the problems that those with severe disabilities have to face or making light of their impediments.

Now to your second point, while a disability is not a changeable condition, but, nonetheless, to my mind, it is not the case that it can't be accommodated with proper techniques, methods and technology. Again, I am not equating the problems (faced by these two classes of people), but I am instead giving my viewpoint and perspective that can help the disabled person recognize that other people have problems, too. For instance, if I start thinking that my hands don't work and I can't walk and I have such huge problems, that will not help me get work done.

In an interview with the American Bar Association, when asked whether any of your work 'advances the rights of persons with disabilities', you stated that your job was to 'apply the law evenly to all those who appear before you' and that you wouldn't award bonus points – or penalise – anyone with a disability. However, some activists have suggested there ought to be more "equitable" applications of law and policy, to correct for historic and systemic injustices. In light of this, what do you think is the role of law in creating a more inclusive and accessible society?

I think I can give you a very specific answer to that. First of all, I am not in a position to comment on how reasonable accommodation should be construed in a statute. Our judicial ethics rules prohibit that. I gave this comment (that you alluded to) in my ABA interview. I still think that's true and that's my philosophy. I have written some opinions on the rights of disabled people. They include a number of statements that address your comments. Two of them dealt with people in wheelchairs. One case dealt with the duty of a shopping centre to make accommodations for those in wheelchairs. Another dealt with the duty of San Francisco to make streets accessible by having curb cuts and making accessible public parks, recreation centres like swimming pools, etc. Another case that I ruled on in this area, not involving the wheelchair-bound, involved the rights of the deaf, in that it dealt with the duty of a county that had a deaf person arrested and in jail who used American Sign Language to provide him an interpreter, for personal interaction and interaction with the guards. When you arrested someone deaf, you couldn't just talk to them or communicate in writing, this opinion said. You had to have an ASL interpreter.

Some of our past interviewees have suggested that attitudinal barriers are by far one of the largest barriers, beyond infrastructural and legal challenges. These barriers can broadly be divided into two heads: the barriers that one faces in developing the right attitude and the barriers that flow from the way in which the society views the disabled. Can you briefly comment on how each of these barriers can be addressed and how you have tackled them in your own career?I'll give you my sense of this with the caveat that I am not an expert on psychology or societal barriers. As must be clear by now, I am a huge believer in the disabled keeping a positive attitude about what they can do and in focusing on what they can do as opposed to what they cannot. I greatly believe in the value gained by this and I try to keep this in mind every day. A person should be willing to accept that if accommodation permits self-help, that is the best way to go.

As to society: I have least expertise in this area. I think that would, in the end, flow from how the disabled treat themselves. For instance, Beethoven composed part of his music while deaf. Some athletes have physical problems, not just fictional characters like Forrest Gump, but actual athletes, too. Further, Stephen Hawking did so much in physics while in his wheelchair. You read about these kinds of things in the newspaper every day. You must have in your cricket teams, as we have in our football teams, athletes facing these kinds of challenges. So, in sum, the disabled should have a positive attitude. If the law permits, they should demand reasonable accommodation. They can find ways to use their mind to adapt and move forward. If they have that attitude and the ability to communicate their needs, people are likely to be supportive.

In his interview to us, Judge David Tatel, who serves on the DC Circuit and is blind, said that he is in a very unique position for a lawyer with a disability, in that he has access to many law clerks and allied resources. In the same way, the key difference between someone in your position and a younger legal professional would perhaps be that your reputation, experience and resources have greatly rendered nugatory any negative impact from having a disability. If you were a younger disabled professional and told by an employer that they are simply unable to accommodate you as this would require investment of more resources and time as compared to what they would have to invest in your able-bodied counterparts, how would you constructively engage with them?

First of all, I agree with Judge Tatel that as a federal judge, I have wonderful resources to assist me. My four law clerks, secretary/judicial assistant and separate personal assistant, who all help to accommodate my needs attributable to my disability. And those are paid for by the government. So I have a large support system. I also have a personal caregiver, who is giving me water from time to time as we talk today. However, if I were younger and starting out, what I would recommend is that I should just try to explain to people how I could get the job done with reasonable accommodation and be specific about what the accommodation is. If my disability had been so severe in the beginning as it is now, I am not sure if I could have persuaded everyone, but I'd have tried to persuade everybody I met. I had practiced for a very long when my MS began taking root. But those who have disabilities can also excel when they start in practice with the disability. For instance, I had a law clerk who was totally blind but I hired her as she did well in law school and has done well since. One of the other judges (on the Ninth Circuit) told me that my prior blind clerk came back (to our Court) and appeared in a subsequent matter and argued a case. According to this judge, she was the best advocate who argued that day. Usually, five to seven cases are argued on a given morning. While working for me, she took full advantage of the assistive technology that was provided to her. These days, everything that is in hard copy can be scanned and, once it is scanned, a blind person can read it. She told the court what she wanted and that enabled her to work at the intense pace required. If I asked her about something, she could always find it and point me to where it was in the brief.

Since your appointment to the bench by President Clinton in 1999, you have served with distinction for almost two decades. In India, courts have espoused the view that someone who is blind cannot be a judge whereas someone with a locomotor disability can. Do you think that such a classification between disabilities inter se has any rational basis, and that it is fair to assume that people with some kinds of disabilities can thrive in the legal profession whereas those with others cannot?

My personal view is that there is no sound reason as to why a blind person cannot be a judge whereas someone with a mobility problem can be. In my 19 years on the bench, we have had blind advocates who have appeared before me more than once. There were those who couldn't stand and had to speak from a wheelchair. We would lower our microphones so that they could speak and we could hear. I don't think there's a limit to what a person with any kind of disability can do to be able to practise successfully, to even be a judge at the highest levels of your court systems.

As someone who developed a disability later in life, would you have any advice to others who may experience something similar? Also, how important, do you think, is it, based on your experience, to have a supportive network of family and friends to come to terms with one's disability?

My advice for the person who has a disability would be to focus on what they can achieve and what they can do and not dwell unduly on their physical limits because they can adapt to their disability. They can use adaptive software and other tools to function to the maximum extent possible. It is very important to have a supportive personal network of family and friends with whom they can speak freely; they are the most important people. They have the disabled person's best interests in mind. I'd not have achieved as much as I have, without the support of my spouse and caregivers who have worked with me for more than a decade. My wife does a million things for me every day from making meals to ordering new shirts when old ones are getting frayed, so the disabled really need their family to assist them. They can purchase assistance with an agency. But they really need family and friends to speak to.

Thank you, that is a very thoughtful, and perhaps the best possible note for us to end this wide-ranging conversation on.

Well I've enjoyed talking with you, and I hope that what I've said is of some help to the important work that you're doing.

Without a doubt Judge Gould! We've taken almost two hours of your precious time, and we're very grateful to you for all the actionable and concrete insights. You've answered all our questions very squarely and in a very concrete way. Is there anything else you'd like to share that we might have missed out on?

No, I want to thank you for your comprehensive set of questions, which challenged me and gave me an opportunity which I appreciated to rethink some of these issues, and I wish you well. Hang in there, get your accommodations, and set the world on fire!

This Interview was first Published Here