Recognition Of Person As 'Tribal' After Transfer Of Land To Non-Tribal Won't Entitle Him To Seek Restoration: Bombay High Court Full Bench

Amisha Shrivastava

19 May 2023 7:15 PM IST

Next Story

19 May 2023 7:15 PM IST

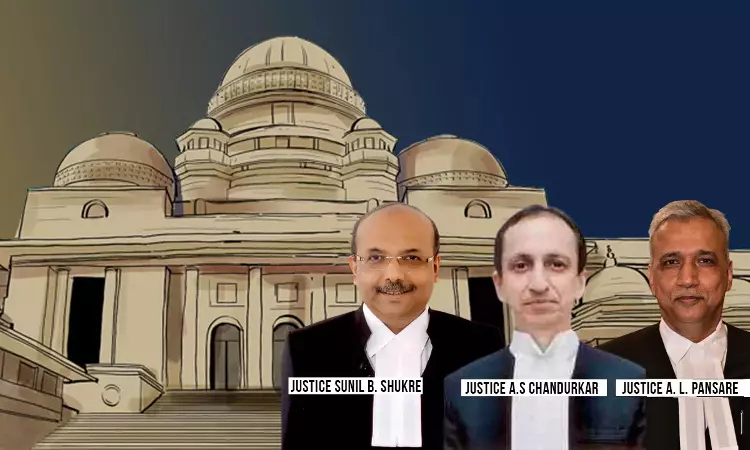

The Bombay High Court recently held that recognition of a person as Tribal after the date he transfers his land to a non-tribal would not entitle the transferrer to restoration of the land under the Maharashtra Restoration of Lands to Scheduled Tribes Act, 1974.A full bench comprising of Justice Sunil B Shukre, Justice AS Chandurkar, and Justice Anil L Pansare sitting at Nagpur...