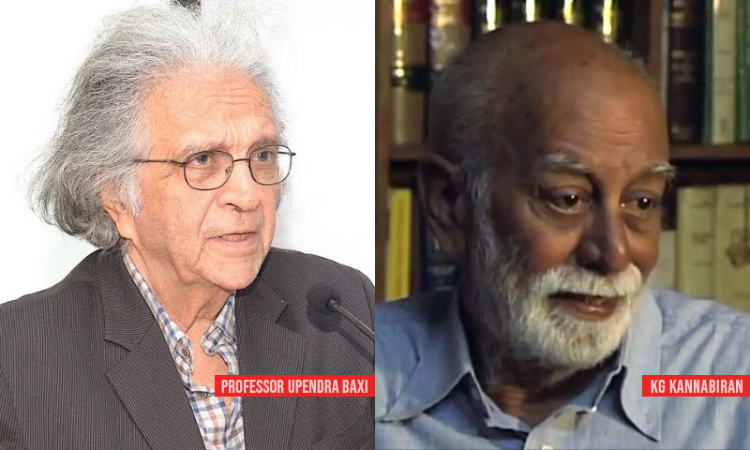

'The Wages Of Struggle : Putting Impunity First' - Dr Upendra Baxi's Talk On Kannabiran Memorial Lectures

LIVELAW NEWS NETWORK

14 Feb 2021 4:26 PM IST

1. Impunity, Democide, Constitutionalism

I wish I had met with KG Kannabiran (fondly known to his family and friends as Kanna) more often than I did, so that I could have learnt and unlearned a lot. I have indeed met more with Vasanth Kannabiran and of course Kalpana Kannabiran in their many professional and activist avatars. Reading Vasanth's memoirs also introduced me to many insecurities and anxieties, which Kanna braved as the head of an adoring family during some difficult moments.[1]

But this invitation by Kalpana to say a few words by way of affectionate memorial to Kanna is also a way of being with him. We have all known a lot more from this lecture series about his many-sided contribution to law and life through addresses by various distinguished colleagues and friends. Kanna has left a wide human right footprint which should become our 'footsteps into future' (here to borrow Rajni Kothari's luminous title of a book that is ever socially relevant).

I originally thought I would address the theme of law and justice in Kanna's thought and action. But one can do this as a matter of high theory or speak to his praxes as illustrating possible approaches to justice. Jurisprudentially speaking, Kanna's notion of 'impunity' is a Hohfeldian jural relation; as such it is strictly a logical relation which implies power in X to place Y into a disability in that relation.[2] I don't know whether Kanna was fond of Hohfeld; I am, even excessively so. While this is not the place to discuss Hohfeldian analysis of impunity, I must say its negative connotation does not always hold in law. In any event, I have chosen Kanna's praxes over theory in this conversation, but it would be fair overall to say that he was a Gandhian but a constitutionalist socialist – a thinker and a doer who de-romanticized practices of violent social action at all sites of power and counter power, but fully believed in the agenda of democratic and pluralist constitutionally desired social order. He had a distinct sense of contradictions of that order but he viewed these positively as making social change possible, rather than a tableau of impossibilities.

I think that I have said it all that needs to be said (if it were humanly possible), in the company of Justice Zak Yacoob of the South African Constitutional Court, in a blurb to his great book The Wages of Impunity.[3] My blurb described Kanna as a 'veteran human rights hero' with a 'relentless integrity in the pursuit of the democratic rights of the disenfranchised'. I further said that 'No one concerned with the future of human rights in India can ignore his eminent voice…'. His voice is even more important worldwide today, because he exemplifies relentless integrity—both as a human rights defender and for the rights-structures as well.

The title of Kanna's book remains somewhat puzzling because impunity-wielding masters of total power have shown a great deal of resilience and remain unfazed and unscathed by claims either of human rights or justice. Even so, such a claim to impunity, whether by state or non-state actors, must be resisted with an agenda of human rights specially 'in a world where all governments are bent upon reducing Hitler and Mussolini to small time operators' (p.12). It is this epidemic of impunity, this performative power, which mocks at both law and justice, that should occupy the foreground of juristic thought and constitutional social action. He firmly believed that impunity even in fighting non-state actors 'is never an answer' and acts of the 'abandonment of governance and civilized conduct on the part of the state' (p.12) ought to be considered a crime against humanity.

Kanna does not deploy the term 'democide' but this what he really means; Professor R. J. Rummel, described this very pithily in the book entitled Death by Government. He lists at least six categories of democide. Lethal sovereignty arises, aside from international war or warlike activities: if it is [i] the intentional killing of an unarmed or disarmed person by government agents acting in their authoritative capacity and pursuant to government policy or high command'; [ii] the 'result of such authoritative government actions carried out with reckless and wanton disregard for the lives of those affected…'; [iii] where 'government promoted or turned a blind eye to these deaths even though they were murders carried out "unofficially" or by private groups…'; [iv] if 'high government officials purposely allowed conditions to continue that were causing mass deaths and issued no public warning', [v] all 'extra-judicial or summary executions… '; and [vi] even 'judicial executions.'[4]

Kanna would have certainy agreed with the observation that growing impunity, like its Siamese twin systematic governance corruption, is a widespread global problem. He would also have endorsed the observation that: 'Impunity is the torturer's most relished tool…. the dictator's greatest and most potent weapon… the victim's ultimate injury.' And, it is 'the international community's most conspicuous failure. Impunity continues to be one of the most prevalent causes of human rights violations in the world...'. In a sense impunity is akin to terror as it 'knows no territorial bounds and speaks no specific language. It is not unique to any religion or race, and is not limited to any particular geographical region. Impunity remains a worldwide problem.'[5]

I have titled this address as putting impunity first. A distinguished political philosopher Judith Shklar has maintained that we should put 'cruelty first' because 'liberalism of fear is a 'mentality […] that regards cruelty as the summum malum, the most evil of all evils' [6] I think Kanna would have no difficulty here—if we were to concede the ranking of among the 'evils of evils'—because impunity is a mother of cruelty.[7]

2. Constitutional Nihilisms and Dismemberment

The global contexts of today have not much use for integrity in either sense and can be best described accurately in terms of constitutional nihilism and constitutional dismemberment. Both these notions relate to constitutional change, but the latter more specifically to the process and power of constitutional amendment, and both these relate in turn to nihilism.

There are many varieties of nihilisms but I prefer, with much narrative risk, to eclectically adapt here Nietzsche's exposition of nihilism as entailing the 'devaluation of the uppermost values' ('passive nihilism') and their replacement by new ones ('active nihilism'.) By values he meant not something that we ought to desire, but strictly the 'constructs of domination'; Martin Heidegger explains this value as 'the increase or decrease of these centres of domination'. Exactly what kind of nihilism is at play and at war when all political parties and even citizens movements today champion the cause of saving the Constitution? No one, of course, can disagree with the idea of saving the Constitution; the difficulty arises when we enquire what in the constitution is endangered and what is to be saved.

For the Supreme Court of India what needs to be saved is the basic structure of the Constitution which has essential features. The basic structure comprises the interpretive power to say what the essential features are, as superadded or subtracted by the court. For the votaries of parliamentary sovereignty, if there is a basic structure it is the constituent power of Parliament to legislate both the changes in and of the Constitution. For Kanna, what was s needed to be always redeemed were the practices and structures of social justice and the democratic virtues of non-violent social disobedience and struggle against injustice. But then others believe in practices of 'active nihilism' wherein the basic values are recast.. This what some call the 'majoritarian' struggle now on in India to remake it into a Bharatiya constitution foregrounding the Hindu values and vision. The question is whether the Supreme Court will give up the co-constituent power it has retroactively and pro-actively assumed over the Constitution.

Kanna did not have before him Professor Albert Richard's subtle and supple distinction between constitutional dismemberment and constitutional amendment. The former goes beyond the correction or elaboration of the existing constitution; it rather 'seeks to deliberately to disassemble one or more of a constitution's elemental parts'; it 'alters a fundamental right, a load-bearing structure, or a core feature of the identity of a constitution. It is a constitutional change understood by political actors and the people to be inconsistent with the constitution at the time the change is made'. Put differently, 'the purpose and effect of a constitutional dismemberment are the same: to unmake a constitution.' Further, constitutional dismemberment can occur by judicial interpretation.[8]

Why may not one offer the traditional view of Carl Schmitt or Hans Kelsen? As is well known the former afforded a distinction between commissariat constitutionalism (adding to it to make such changes as are generally consistent with its basic structure and essential features, to use here the concepts of the Supreme Court of India) or replacing the old constitution by a new one (expressing the will of the People). On the other hand, to deploy a difficult notion of Kelsen, a change sought to be effected by the change in the Grundnorm of such a proportion as to entail a new basis for the Constitution which has to be by and large effective in order to be valid. Whether the new constitutional order is just or unjust, good or bad is a matter of how it all appears to the subsequent act of demosprudential judgment.

Dismemberment as a descriptive concept….s 'a self-conscious effort perceived as the unmaking of the constitution with recourse to the rules of constitutional alteration', but a 'substantive change' which is 'incompatible with the constitution's existing framework and purpose'. Yet, such a change 'introduces a transformative change to the constitution, but it does not produce a new constitution.'[9] Dismemberment is 'constitutionally continuous transformation that can occur suddenly in a big bang moment of constitution-unmaking or gradually by erosion or accretion …' It 'can occur with the effect of either enhancing or deteriorating liberal democracy'. These changes are 'often described as amendments' but 'they are amendments in name alone…best understood as dismemberments.'[10]

What this approach does is to avoid the amorphous nature of 'We, the People' and their real or imputed will. It also offers us dismemberment as a descriptive rather than normative/evaluative process, which involves the use of amending powers as ushering in some changes in the Constitution, some far reaching as to be changes of the Constitution, in the 'constitutional rights, structure, and identity'.[11] It lies far beyond the scope of the present conversation to explore and critique this theme further,[12] but we may say that Kanna took a very practical path and emerged as a strong defender of human rights and a champion for accountability of the power of the few to injure and damage the life and well-being of millions. He described the trends towards democratic recession in India and took a strong exception to what we may now recognize as early forms of constitutional dismemberment. His was an explicitly normative view of the processes of dismemberment as far as these effected the integrity of rights-structures.

3. Professional and Passional Activism: A Lawyer's Struggle

Not all activism is the same, though there may be similarity of outcomes. This is not the place to outline a general theory of activism,[13] but it must be said that we stand in some mortal danger of misunderstanding Kanna's life and message when we forget the differences among types of activism. Archetypal are two kinds of basic discourses: the discourse of passional activism and discourse of professional activism; and the discourses of Astroturf and grassroots activism. The latter occurs often as a spontaneous and often leaderless social movement. Kanna's was no remote activism; in fact, he did not believe in Astroturf activism; his was grassroots activism. Grounded and situational activism that was tempered by ways of being at the state level Bar; his was also a professional activism that sought to deliver legal services to just causes. Legal profession, at least in the common law orbit, teaches us that recourse to law and courts does not always lead to the success of a just case and cause; often just causes are lost causes. But, rightly, Kanna believed that what mattered was not winning or losing; what mattered after all are deposits of justice that a lawyer inputs and residues of justice that remain in, and for, the future judicial discourse. In a way, legal professional experience is a continuous education in the virtues and values of learning and unlearning, and conversion of present despair into a future triumph.

'Professional activism' is grounded in the time of dedication to the arts and crafts of one's chosen learned profession, which is both learned( in terms of skills and competence) and highly competitive. Kanna's enclave, within legal practice, was mainly criminal, labour, and constitutional law. Many lectures in this series pay, rightly, a high tribute to his eminence in these fields. He also was in constant demand by the State for his skills at mediation with Naxalite leaders or groups, which reached new heights with each incident.

At the risk of digression, I mustt look at, with you, my first foray into describing legal consciousness. At a meeting of Indian Law Teachers Association at Hyderabad I addressed the theme of 'What the Convicts of Rajahmundry Prison Can Teach Us'. That paper focused on devastating cyclone which occurred in the then State of Andhra Pradesh and the prison break in Rajahmundry prison that occurred within that setting.[14] I there contested legal consciousness in two forms: everyday legal consciousness (ELC) and professional legal consciousness(PLC), which I also dubbed 'All India Reporter Legal consciousness.' The latter form arose out of a study of reported cases, and remained s particularly the estate of law teachers who spoke after every other legal decision-maker had spoken, thus accepting the lowest position in the hierarchy of legal knowledge. In contrast, the professional lawyer developed an interactive understanding of ELC and PLC; AIR consciousness emerged truly in a Benthamite conception which guided us to the central fact that law is settled, or made constantly, by 'judges in company' (the judicial actor in conversation with lawyers in the instant case and generally).

Kanna as I imagined him in action, saw in a judge or a bench an invitation to reshape the law; this came almost naturally to him as he believed in a conception of PLC that included both the task of expounding the law as it is and what it ought to be. His notion of the judicial role was thus many layered and deeply and socially embedded and culturally sedimented. He appreciated the value of order in social and individual life but developed conceptions of order that were neither authoritarian or disciplinarian. He did not wish law to be an instrument of autocratic order but a vehicle for a just constitutional order. And he believed that lawyers and justices in promoting conceptions of just life under the constitution are best fitted to sculpt conceptions of order that best promote freedom of all (which I have called state free spaces as compared with state filled spaces); constitutional pluralism, being always reasonable pluralism, was inherent, for Kanna, to the very idea of constitutionalism. Put another way, lawyers and justices may not only be the shoulders of the state (and the 'free market') but the soldiers of the Constitution (this last phrase was invented by Dr Chhatrapati Singh during our first UGC sponsored Law Curricular Development meeting – in 1993-4).

I must add that legal professional intervention can also arise from citizen's petitions, which Lotika Sarkar and I were privileged to initiate as 'social action litigation' (SAL). We discovered that representing the disenfranchised requires a partnership with all learned professions. Engagement with medical profession proved critical in pursuing the constitutional goal of gender justice in Agra Home case particularly in HIV cases. Other matters that I pursued showed how in the Bhopal litigation, one required help from medical and other scientists; and the public initiatives of the Medico-Legal Friends Circle were extremely valuable. In the Tehri Dam petitions, I was helped both by institute of earthquake engineering and in Kesari Dal petitions by the National Institute of Nutrition. The labours of the National Institute of Design were decisive for us in the petition regarding 'accidents' systemically caused by earlier thresher designs, which deprived farmers of limbs and even life. Environmental law and jurisprudence owes its wildfire development to the engagement of well- qualified technical experts in various fields of science and technology.

I learnt early about the value of multi-disciplinary partnership between the scientific estate and attainment of human rights and social justice. Finding the experimentation insufficient, I suggested, beyond the ad hoc panels, variety of ways in which the Supreme Court can institutionalize this partnership; sadly, the suggestions have still to be followed! Kanna's activism, on the other hand, displays the remarkable strengths of unidisciplinary initiatives using the tools and the crafts of existing law for actively promoting human rights and justice.

Kanna was not, for the lack of a better word, a career activist, one who leads the life of a professional activist, and operates the investor confidence in the markets of human rights.[15] Nor was his an academic activism which romanticized the ways of changing the local or global worlds by dint of teaching, research, and communication. He pursued an eminent career at the Bar and the best way is to recall him as an exemplar of how to use legal competence, skill, and performative power to influence directions of planned amelioration of social injustice. I always follow Kanna in primarily empasisizing legal activism at the service of, and in search of, justice.

It is in the sense of lawyerly professional activism that Kanna was concerned with what he saw as institutional decline and decay in maintaining the integrity of institutions of democracy and to arrest institutional degradation of democracy. Democide functioned here to signify the slow but sure death degradation of democratic institutions.

But he was also concerned with the slow and steady institutional erosion of Indian constitutionalism. In his time, there was little discourse about 'democratic recession' or the three waves of democratization in the world. But India had a brief spell of savage repression and denial of basic human rights during the internal emergency of 1975 —76 . This trend has not just resulted the idea of 'committed judiciary' but also led overall, Kanna says valiantly, to a 'moth eaten' system being 'destroyed both from within and by the government'[16] and the present system of appointments to the judiciary … whose only merit would be access to the ruling power structures'[17]. It is, perhaps, more true than in the past to recall his acute remark that 'the mere presence of a nominally functioning institution does not by itself enhance its democratic content' and it needs to be related to, and 'rooted in the life of a community and has to be related' to 'its need'[18]. But how far does the acquisition and conduct of political power correspond to, in real life, to the 'life of the community', is a question that remains subject to empirical validation in every generation. Kanna is quite right in emphasizing the mere existence of institutions from those functioning organically with the people.

But his observation, however, raises a more fundamental question as to what needs to be done when constitutional morality (which he applauds) is deeply at deep variance with extra-constitutional public morality. I have analysed this conflict elsewhere;[19] all that I need to say here is that the adjudicative demosprudential leadership of the nation is often not readily accepted by the 'community' extolling hierarchical domination, and justifications of graded equality and violent social exclusion often parade as a democratic virtue.

Undoubtedly, there is globally a 'democratic recession' identified as 'a class of regimes' that have 'experienced significant erosion in electoral fairness, political pluralism, and civic space for opposition and dissent, typically as a result of abusive executives intent upon concentrating their personal power and entrenching ruling-party hegemony'.[20] Democratic recession has been also marked by a 'trend of declining freedom in a number of countries and regions since 2005'.[21] Yet, it has also been noted that democracy 'may be receding somewhat in practice, but it is still globally ascendant in peoples' values and aspirations'.[22] Kanna (naturally unfamiliar with this later discourse, and its empirics) had unerringly identified executive despotism and governance impunity as root causes of incipient democratic recession in India.

As a professional activist, he for example, articulates concerns with this recession both with the decay in the Bar and Bench. Kanna observes that 'we find increasing signs of a totalitarian system of governance' even as early as the 'second decade of the Constitution'. He echoes the then emergent ideological critique of the Supreme Court's 'blocking of even minimal reform measures introduced by the government without which the country could not be peacefully governed'. He has in view some early controversial decisions which elevated the right to property over 'land reforms'. Kanna finds it deeply ironical that 'while the right to property was registering victories in the courts, restraints on personal liberty had the approval of the court'.[23]

Kanna simultaneously notes that 'the legal talent that was available to these holders of unearned property was phenomenal. They even 'managed to get Dr. Ambedkar, who had authored and steered the Fundamental Rights chapter of the Constitution, to appear for one of the zamindars of Bihar'. He further observes that 'the drafting of the Constitution produced a crop of lawyers who halted or stalled the progress of the country towards its constitutional goal right from the beginning. No litigation over estates or private property provided as much wealth to lawyers as the Constitution of this democratic republic'[24]. This is a grave indictment of the first decades of the apex court justices and lawyers. Professional Bar from early days emerged as a seller's market. The legal profession as a class emerged as a champion of civil liberties but it has also simultaneously served the interests of those that had rights leaving the dispossessed (the so- called 'weaker sections of society') forever rightless. Even the Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and other backward classes continue to inhabit the vast continent of unmet legal needs, though some senior counsel have emerged to offer free legal representation (especially after the Emergency of 1975-76); this marks radicalization of at least some sections of legal profession.

Kanna has a word, too, about the steel frame of Indian bureaucracy which Rajiv Gandhi described poignantly as 'the fence which ate the crop'. Kanna writes less colourfully, but with equal accuracy, that the 'administrative system as a whole' was not 'geared to perform the fundamental obligations of the State set out in the Directives chapter of the Constitution'.[25] Yet other different interpretations at least of the judicial approach have been plausibly urged.

4. CJA vs CJS

Criminal law and justice was a passion with Kanna for many reasons. He thought that it was on this terrain that the battles for human rights are best waged because the might of the state here confronts the suspect and the accused. And here, too, the concern for the small person, who has no access to social networks, and is disadvantaged, disenfranchised, and depressed ought to manifest itself. There is of course the fundamental right against self-incrimination, the right to a legal practitioner of one's own choice, even the right to life and liberty, sonorous directive principles ensuring access to justice, and the Supreme Court enunciations now of a right of access to judicial infrastructure, and yet the law as it operates fails to respect this normative discursivity. There is no gainsaying that criminal law as it operates offers us vividly two 'systems' of administration of justice; the one for the economically better off with access to the privileged networks of power and influence and the other for the constitutional have-nots. And Kanna spent a luminous lifetime struggling against this institutional bias in the Indian legal order that led Justice Krishna Iyer to inimitably say that as far as the impoverished masses of India what we have is not administration of criminal justice but criminal administration of justice.

Howsoever unpleasant it may be to the comfortable middle classes, even they ought to face this reality of the duality in criminal justice administration. The duality is endlessly reproduced. First, the Constitution of India enacts this duality in terms of 'preventive detention' and criminal law 'system'. Second, the duality of using the norms of criminal law against political adversaries and dissenters has steadily displaced the notion that that it is in a well-ordered society of decent peoples (to pinch here a favourite expression of John Rawls); criminal law is only used for the collective security of the population as a whole and not for party political strife or electoral gain. Third, the inveterate duality of differential application of law—impunity for the incumbents and continuous harassment of the adversaries is not any of the aims of criminal justice yet practised by all political regimes since the independence. Fourth, multiple legal regimes today work on the principle of reversing the onus of proof on the accused rather than presumption of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Fifth, despite valorous pronouncements from high judicial pulpit, bail remains an exception and jail the norm; prolonged incarceration during investigation, and as accused awaiting trial, or as convict appealing against the first judicial finding of guilt, are considered 'normal' aspects of criminal law, whereas it would be highly scandalous in a decent legal ordering. Sixth, there is no of compensation for wrongful detention or conviction (and as Innocence Projects have shown globally) rendering adjudicative and executive acts of compensation both ad hoc and arbitrary. Seventh, is the lack and unevenness of legal practitioners of one's choosing; since the Advocates Act casts no duty on lawyers to fulfil the unmet legal needs for representation while assuring lawyers right to practice (as an aspect of Article 19 fundamental right to choose trade, profession, or business), legal services are an incident of the seller's market; and it would forever take long to provide sufficient legal services by way of statutory legal aid programmes. And eighth, there is no provision in law providing for counsel presence during investigation on an a priori assumption that this will 'hamper' expeditious and effective investigation—an aspiration though well formulated in words, still rarely realized in action.

All this not too say that police do not perform a valuable social security service; they do and in a number of ways. Nor to say that the levels of public confidence in police has ebbed; as the constant demand for a CBI or SIT (special instigating teams) show. As a matter of social practice, police efficiency and ability to do a reasonably expeditious job seems trusted at least by those who have some property (which Justice Krishna Iyer called 'propertaryiat'): and there exist any number of cases where even the proletariat trusts professional policing. However, spectacular and poignant cases of enhanced interrogation exist, custodial torture abounds, encounter killings become routine policing techniques of crime control, and impunity grows apace. And everyone agrees that Indian society needs both democratic and efficient policing. The Indian political class as a whole continues to prefer to control policing for partisan purposes, rather than to meet social needs or expectations. I have been saying it since the seventies e but only Kanna, amongst us all, has seen the law as a decisive battleground for accountability: justice, for him, is always putting impunity first.[26]

Surely, what is needed is the conversion of the present non-system into a system; or to convert the ACJ into CJS.[27] We have a right to a CJS , if only to minimize the penal process itself from being a whole series of evils (as Jeremy Bentham said (as said acutely in 1840), resulting from the original and pervasive evil of infraction of liberty.[28] Kanna would have agreed; treatment or punishment should avoid all preventable harms and surplus and preventable suffering (extra-legal or illegal deprivations of human liberty) at all costs. This is a message of justice we need for each generation and for all institutions, networks, and assemblages of state law.[29]

This message today remains sharpened by the anti-impunity discourse, especially in the spheres of human rights,[30] transitional justice,[31] and border crimes.[32] Kanna would have been delighted to know, and further develop, this discourse—especially the concept of 'impunity gap'[33] had he been with us in the global today. But we owe it to the memory and inheritance of Kanna to recall his putting 'impunity' first, among a handful of modern Third World legal thinkers, as a marker of a just and humane society.

First Lecture by Justice B Sudershan Reddy, former Supreme Court Judge -Death Of Democratic Institutions: The Inevitable Logic of Neo-Liberal Political Economy & Abandonment of Directive Principles of State Policy.

Fifth lecture by Justice K Chandru : Need For More Kannabirans Felt Now With Ever Increasing Human Rights Violations : Justice K Chandru

Sixth lecture by Advocate BB Mohan : Criminal Law and Human Rights: 'Distinctive Discrimination' and Article 21 Rights to Fair Trial

Seventh lecture by Advocate V Raghu : The Constitution and Scheduled Tribes in Composite State of AP

Eighth lecture by Justice J Chelameswar, former Supreme Court judge : Periodic Audit Of Performance Of Individual Judges & Judiciary Needed To Maintain Standards : Justice Chelameswar

Ninth lecture by Senior Adv Dr Colin Gonsalves : Two Supreme Court Judgments Killed The Working Class & Converted India Into A Country Of Slaves: Colin Gonsalves In KG Kannabiran Lecture

Tenth Lecture by Advocate Henri Tiphagne : Defending Human Rights, Challenging State Impunity : Henri Tiphagne's Talk At Kannabiran Lecture

ENDNOTES

[1] Kannabiran, Vasanth. 2020. Taken at the Flood: A Memoir of Political Life, New Delhi: Women Unlimited.

[2] The concept of jural relations is found first in Friedrich Karl von Savigny, Jural Relations, or, The Roman Law of Persons as Subjects of Jural Relations: Being a Translation of the Second Book of Friedrich Karl von Savigny's System of Modern Roman Law, sec. 60 (London, Wildy and Sons, 1884. W.H. Rattigan, t rans.) But it found its first exposition in Wesley Newcombe Hohfeld, 'Some Fundamental Legal Conceptions as Applied in Judicial Reasoning', Yale Law Journal 23:1, 16- 58 (November 1913). See also, Matthew H. Kramer, 'Rights Without Trimmings' in Matthew H. Kramer, N. E. Simmonds and Hillel Steiner, A Debate over Rights: Philosophical Enquiries, 7-112 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), Laura K. Donohue, 'Correlation and Constitutional Rights', (2020) Georgetown Law Faculty Publications and Other Works. 2303. Available at https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/2303.

[3] Kannabiran, K.G. 2003. The Wages of Impunity: Power, Justice, and Human Rights. Delhi: Orient Longman. This book hereafter will simply as Wages and page numbers in parentheses refer to this book. I however rely for page numbers in the scanned copy that Kalpana and Ramya have graciously provided me for personal use.

[4] See, Rummel, R.J. 1994 Death by Government: Genocide and Mass Murder in the Twentieth Century, (NJ: Transaction Press, 1994; Rummel, R.J. 1994. Power Kills. Democracy as a Method of Nonviolence. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Press; Saucier, Gerard and Laura Akers, 2018. 'Democidal Thinking: Patterns in the Mindset Behind Organized Mass Killing', Genocide Studies and Prevention 12, 1: 80-97; Kannabiran, Wages, Chapter 2.

[5] Penrose, Mary Margaret. 1992. 'Impunity—Inertia, Inaction, and Invalidity: A Literature Review', Boston University International Law Journal, 269.

[6] See Shklar, Judith N. 2006. 'Putting Cruelty First', Democratiya, 4, Spring, 81–94. For a critique , see , Fives Allyn, 'The unnoticed monism of Judith Shklar's liberalism of fear', Journal of Philosophy and Social Criticism, ,(2019): https://doi.org/10.1177/0191453719849717.

[7] The United Nations Convention on torture for example speaks of Torture, and other Inhuman, Cruel, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, which came into force on 26 June, 1987). Ratified now by a very large majority of United Nations member states, India counts among a handful of countries ( including China and Pakistan) who have yet to do so.

[8] Albert, Richard. 2018. 'Constitutional Amendment and Dismemberment', Yale Journal of International Law. 43:1-84, at 4.

[9] Id., at 14.

[10] Id., at 3.

[11] Id., 3-50.

[12] See Baxi, Upendra, in Comparative Constitutionalism and Constitutional Identity (Jacobsohn Festschrift forthcoming, 2021); Yaniiv Roznai ed.

[13] See, for a preliminary attempt, Baxi, Upendra, The Future of Human Rights, Chapters 3 and 7. 3rd edition (Delhi, Oxford University Press, 2013; the 4th edition now in press, forthcoming 2021). Hereafter Future.

[14] Keynote Address, December 1 ,1977; my stencilled paper (it is difficult to read all of it in the original, which Professor Tulsian read and heavily marked, and then passed on to his student Ms. Ayushi Gupta ( then a graduate student in the law faculty , Delhi University). She re-sent the text to me from Oklahoma, USA, where she did her LLM. She re-introduced me to him as her guru (Swami Shyam, whom I knew as Shyam Sunder Tulsian) and it was a festival of memory for us when we met in my house at Delhi. I am grateful to Professor Kalpana Kannabiran who arranged for a retyping of the paper which will shortly appear in academia.com.

[15] Baxi, Future, Chapter 7.

[16] Kannabiran, Wages, p. 207.

[17] Id at 206.

[18] Id.

[19] Baxi, Upendra. 2019. 'Whither Constitutional Morality? Some Thoughts on Justice Dipak Misra's Enunciations', 263-277 in Krishna Deva Rao, S, ed. Reclaiming Justice, Rights, and Dignity: Essays in Honour of Justices Dipak Misra. Delhi: Thompson Reuter. See also, Khurshid, Salman, 2020. 'Constitutional Morality and the Judges of the Supreme Court' in Salman Khurshid, Siddharth Luthra, Lokendra Malik, Shruti Bedi, eds Judicial Review: Processes, Powers, and Problems: Essays in Honour of Professor Upendra Baxi, 384-410. Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

[20] Diamond Larry. 2015. 'Facing up to Democratic Recession' in Diamond, Larry and Marc F. Plattner, ed Democracy in Decline. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 88-118, 106. See also, Noam Chomsky, 2008. Failed States: The Abuse of Power and the Assault On Democracy. New York: Metropolitan Books.

[21] See, Diamond, supra note 15, at 107.

[22] Id. at 116.

[23] Kannabiran, Wages, pp. 45-46.

[24]. Id at 48.

[25] Id.

[26] Some of these suggestions are discussed in detail in the forthcoming article entitled: see, Baxi, Upendra, 2020. 'Human Rights in the Administration of Criminal Justice: The Concept of Fair Trial', Journal of the Human Rights Commission of India, 1-22 (December).

[27] This has been the central message of the above- mentioned paper.

[28] See, Baxi, Upendra (ed). Bentham's Theory of Legislation Delhi: LexisNexis (11th Edn, reprinted 2012). See also, 'An Introduction to Jeremy Bentham's Theory of Punishment, UCL Bentham Project, Journal of Bentham Studies, vol. 5 (2002) at discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1323717/1/005 Draper 2002.pdf.

[29] And also the non-state systems handling of disputes where violent social exclusion prevails as a norm for social deviance transgressing community customs. I have been a lifelong student of Indian legal pluralism: see my most recent publication, Baxi, Upendra. 2020. '"A Community of Judges?": Some Reflections on Reading Kalindi Kokal, State Law, Dispute Processing, and Legal Pluralism Unspoken Dialogues from Rural India', South Asia Research l. 4: 3.

[30] See, Engle, Karen et. al. Note 31, infra.[31] See; Paige, Arthur. 2009. 'How Transitions Reshaped Human Rights: A Conceptual History of Transitional Justice', Hum. Rts. Q.4: 321: 323-324; Benomar, Jamal. 1993. 'Confronting the Past: Justice After Transitions', Journal of Democracy 4: 3-14; Engle, Karen (ed). 2016. Anti-Impunity and the Human Rights Agenda. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[32] Mann, Itamar. The New Impunity: Border Violence As Crime', https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3619726 University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Law, Forthcoming.

[33] Duffy, Helen. 1999. 'Toward Eradicating Impunity: The Establishment of an International Criminal Court', 26 Soc. Just. 115, 116.