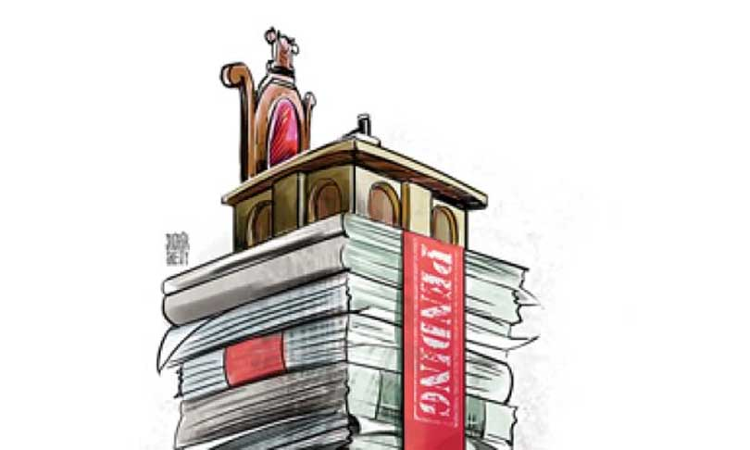

Judicial Delays: Will the Supreme Court's 'postscript' In Facebook Judgment Rock The Boat?

Sidharth Sharma

16 July 2021 7:59 AM IST

Enough has been said and written about the 'reforms' needed to solve the problem of huge pendency of cases that faces our judiciary at all levels. What remains elusive is implementation. The problem of pendency continues, and its enormity is increasing by the day. Even in the absence of the big-ticket reforms and despite all the constraints of manpower and infrastructure, can the system do better? this is a question that both, the members of the bar and the bench ought to ponder over.

That this aspect is troubling the judges of the highest court is evident from an unusual, but not surprising, 'postscript' that a 3-Judge bench of the Supreme Court wrote to its recent judgment in AjitMohan v. Legislative Assembly, Delhi ('Facebook case'). The postscript is thought-provoking and has come as a breeze of fresh air, for it seeks to bring focus over those aspects of the justice delivery process which do not get the attention as much as they should. It also seeks to change the routine which, it appears, we all have got too comfortable with and have come to accept as the 'normal'.

A Double Whammy

Even a delayed process can be predictable. However, our justice delivery system at present suffers from a double whammy: of delay and unpredictability. And it is not about unpredictability (or uncertainty) of the final outcome. That is bound to be there in any judicial process. As they say, justice discriminates according to merit and does not guarantee equality of outcomes. But then procedurally, the system can be – must be – certain and predictable.

This problem exists at all levels of the judicial hierarchy. Let's take the Supreme Court for example.

Given the current load of pending cases and the number of judges in the Supreme Court, let's say one should not expect the final hearing of a newly admitted appeal for the next three years. But can the system predict, with a fair degree of certainty, that after three years, the case will be listed for hearing? And after it is listed on a particular day, the case will actually be heard on that very day? As things stand today, one can't say.

It is like standing in a long queue waiting for your turn. The wait can be annoying, but it is still okay if one knows with a fair degree of certainty when one's turn would come. But imagine if you join the queue which is not only slow moving but also unpredictable. That can be frustrating.

The Supreme Court does not have a calendar for final hearing of matters. As a result, lawyers too can't have a calendar of their own and stick to it. The 'case status' on the Court's website may show a likely date of listing but that is computer generated and has no certainty attached to it. So overall, things are always in the zone of being tentative and hence, uncertain. This has given rise to a vicious circle.

Lawyers, since they are not certain if and when their matters will be listed and heard, make requests for passover and adjournment. Judges grant those requests and switch to the next matter, as there are always plenty of other matters on the list.

The Imponderables

When a matter appears on the list for final hearing, and the lawyers and the client get together for a conference to brief the lead counsel, the usual questions are: "will it reach?", "will they hear it?"

In summary, the final hearing of a matter in the Supreme Court may go though one or more or all of these imponderables before the matter is finally heard and decided:

- There is no certainty when your matter will be listed for final hearing, or how much of a prior notice, with certainty, one would get about the listing.

- When the matter does get listed, but if the lead counsel is not available on the date of listing, the matter may be 'mentioned' or a letter for adjournment may be circulated.

- Even if you and your lead counsel are ready with the matter, there is no guarantee that it will be heard that day: your matter may not 'reach' because the matter or matters ahead of yours don't finish. There is no time limit specified for oral submissions. Oral hearing of matters may be spread over days, weeks or even months. With a big gap in days of hearing, often one will have to recapitulate and repeat what was argued previously.

- If your matter is low on the Board, still you can't leave the courtroom thinking that the matter will reach only later in the day. The Board may suddenly 'collapse' and your matter can be called out. So you remain on tenterhooks.

- Even if your matter is high on the board and reaches, the other side may take an adjournment or passover. In most cases, the request would be granted. Your preparation for the day goes down the drain. The client bears the cost and can only hope for a better luck the next time – and it may not always be the very next day – when the matter gets listed.

- Just a day before the date of hearing, you may be notified that the Bench is not sitting the next day or it is only sitting in the first half, and in the second half the judges are sitting in a different 'combination'.

- When the matter reaches, one of the judges might recuse or the matter may be directed to be listed before another Bench.

- In some cases, when your luck is really bad, even after the matter is heard, you may not get a judgment. If one of the justices on the Bench retires before pronouncement of the judgment (yes, it has happened), then the matter will have to be reheard. When, one can't say. You basically start all over again.

In all this, there is a criminal waste of time and resources. And it is mostly the clients who suffer and so does the respect for the judicial process, though nobody says it openly. For individual clients, the litigation proves prohibitively costly. While corporates may be able to bear the cost of an unproductive day in court, that's not something desirable. Even for a financially well heeled client, it is very frustrating to be told, after the case is listed and resources are deployed in preparation for the hearing, that the "matter did not reach" or was "mentioned" and "adjourned".

This uncertainty and unpredictability of the process also creates procedural asymmetry and even otherwise valid and well-intentioned decisions come in for criticism. For example, when the Supreme Court recently took up the matter of bail in the case of a journalist and passed an order that was laudable from the standpoint of personal liberty and role of the constitutional courts in protecting it, the move was criticized for being preferential in listing and hearing the matter. Similarly, if hearing in a big dispute involving corporates gets completed and decided swiftly, it is criticized whereas the swift disposal should be welcomed. What is happening currently is that judges try their best to accommodate final hearing of important matters. But since the process is ad hoc, it leaves itself open to criticism.

Disciplining The Process

The postscript in Facebook case refers to the problem of lengthy oral arguments, preceded or followed by equally lengthy written submissions, notes and (in)convenience compilations filed liberally.

Fixing a time limit for oral arguments is indisputably imperative but it may not work unless greater importance is attached to drafting and sanctity of written words. The oral submission-centric adjudication process has led to drafting becoming the least important part of the whole process. Since there is not much rigour applied to drafting and there is no word limit to how much one can write, brevity becomes a casualty. It is considered safe to write more instead of less. And once filed, these lengthy appeals and petitions are seldom read fully by anybody. The current system attaches little or zero premium to a concise and crisp drafting (the importance of which the postscript emphasizes), and consequently there is little motivation or incentive for lawyers to work towards that.

It is amazing how we lawyers can draft up to 26 'grounds' (A to Z), and sometimes even more, in a special leave petition (SLP). SLPs are meant to be based on grounds of very serious errors of law. If there are 26 errors in the impugned order, and hence as many grounds to challenge it, then such matters should be archived as case studies – either for those many serious errors in the impugned order or for the ingenuity of the lawyer who drafted the petition!

A restricted time limit for oral submissions will also require a rigorous pre-hearing reading of the brief and written submissions by the judges. Only then can they keep the oral submissions on a tight leash. The US Supreme Court requires parties to file a 'Merits Brief' which has a word limit. That sets the boundary for the oral hearing.

Why parties cannot exchange and file in advance, the case laws, notes of arguments and List of Dates that they seek to rely upon during the oral hearing? Also, it is difficult to understand why 10-20 matters are listed on a final hearing day? On a normal day there is just about five hours available for a Supreme Court bench to hear matters. In that timeframe, not more than two to three final hearing matters can be fully heard. It is practically impossible for the judges, with their enormous workload, to read and prepare themselves fully for more matters. The oral hearings are then bound to take longer and may even be necessary.

It is remarkable how the Supreme Court keeps the process going. Despite all the cynicism and criticism, it continues to be the last and in many cases, the only hope for justice. It is for the sake of this faith and hope that there is a serious and obvious need to make the justice delivery process better. For that, no large-scale 'reform' or huge 'budgets' are required. What is required is discipline from all the participants – the Bench, the Bar and the litigants. And the discipline has to be uniformly enforced. Any relaxation should be allowed only in very exceptional circumstances that should be well-defined.

The problem is that the degree of discipline demanded by the Court differs from Bench to Bench. So, you have benches which are considered 'strict' and others which are seen as 'liberal'. This creates a moral hazard and also procedural arbitrage depending on which Bench your matter is listed before. Recently, the Bench of Justices D.Y. Chandrachud and M.R. Shah expressed anguish over the adjournment-seeking practice of lawyers, and how final hearing matters, after they are put on the back-burner due to adjournments, remain pending. Their anguish is legitimate. That approach has to be applied across all benches, to all cases and to all lawyers – even if that entails rocking the boat. Will it be done?

One may dismiss it by saying that we can't compare ourselves with the United States, but it is worth reading the 'Guide for Counsel in Cases to be Argued' available on the website of the Supreme Court of the United States. It shows the sanctity and discipline that is attached to proceedings before the highest court in the land.

One hopes that the postscript in the Facebook case would prompt a change at our highest court, to start with. That will then gradually have a trickle-down effect on the courts below. This change will not solve the problem of pendency and the wait for final disposal might even become longer. But it will definitely bring in the much-needed predictability and certainty to the judicial process. The double whammy should end.

(The writer is a Delhi-based lawyer and an advocate-on-record at the Supreme Court. Views are personal).