In July 2011, a panel of Justice B. Sudarshan Reddy (who was slated to retire from office that week) and Justice S.S. Nijjar declared the establishment of Salwa Judum unconstitutional and ordered that it be disbanded immediately. It also directed an immediate end to the deployment of the SPOs in counter-insurgency operations. The state and central governments were censured for their conduct from the time of the filing of the PIL in 2005.The state government was criticized for making misleading statements about its progress in complying with the court's directions. The Supreme Court expressed its 'deepest dismay' with the central government for abdicating its constitutional responsibility by arguing that law and order was a 'state subject' and that it had no role in determining how SPOs would be recruited, trained or deployed.

The Supreme Court concluded its decision with a number of orders to the government of Chhattisgarh and the central government. All efforts were to be made to recall firearms provided to SPOs. Former SPOs were to be protected from revenge attacks by Naxalites. In future, SPOs could only be appointed to assist in disaster relief efforts and to regulate traffic, not to combat insurgents. The state government was ordered not only to prevent the operation of Salwa Judum, but also to promptly and diligently prosecute its past criminal activities.

This was a courageous decision. Prime Minister Manmohan Singh had in 2006 described Naxalism as the 'single biggest internal security challenge' that India had ever faced. As some of the other chapters in this book demonstrate, Indian courts – much like their counterparts in other regions of the world – are often reticent when confronted with questions of national security. The court did not mince its words, and neither did the news headlines of the time: 'SC terms arming Salwa Judum "unconstitutional"', 'Salwa Judum is illegal, says Supreme Court', 'Salwa Judum is illegal, scrap it, says SC'. With a BJP government in the state and the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government in Delhi, posturing over what the judgement represented and who was to be held politically accountable began immediately.

Equally significant as the court's decision, however, was its diagnosis of the socio-economic causes behind the state of affairs in Chhattisgarh. The first twenty-two paragraphs of its judgement condemned the policies of the state, which privileged the interests of the extractive mining industry over those of the Adivasis. This sense of disenchantment against the state fuelled social unrest and established an environment in which Naxalism was able to thrive. For the court, this case was symbolic of 'a yawning gap between the promise of principled exercise of power in a constitutional democracy, and the reality of the situation in Chhattisgarh' caused by '[p]redatory forms of capitalism'.

These observations – seen as going beyond the institutional competence of the Supreme Court – were not well received. An Economic Times editorial criticized the court for passing 'facile judgement on economic paradigms and development strategies' and offering 'legitimacy to populist rants' on neo-liberalism. In an indirect reference to the court's judgement, Arun Jaitley (who would later become union finance minister) noted that it was not for the court to debate the merits of economic liberalization – the 'Supreme Court of India cannot have an economic philosophy'.

Shortly after the court's decision, the UPA government at the centre as well as the BJP-led state government in Chhattisgarh began exploring options to overturn the decision. The central government's primary concern was the knock-on effect that the decision would have on SPOs appointed in other states. Although Chhattisgarh was the only state represented at the hearing, there were passages from the decision that could be read as applying to SPOs across the country. More than 50,000 SPOs were employed in various states aside from Chhattisgarh at the time – with over 30,000 in Jammu and Kashmir alone, and the balance spread across Odisha, Jharkhand, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

When asked about how it would respond to the decision, the minister of state for home affairs first noted in the Rajya Sabha that the central government was discussing the matter in consultation with the law ministry. Following a few rounds of discussion with Attorney General Goolam Vahanvati, the plan that was originally envisaged was to file a petition seeking a review of the court's decision. However, thereafter the central government instead chose to file an application seeking a clarification on the scope of the decision. That application proved successful, with the Supreme Court clarifying that its decision was restricted to Chhattisgarh. The damage limitation exercise was complete, and the central government no longer needed to be concerned about the tentacles of the decision extending to other states with SPOs.

The state government's initial thinking was also to file a review petition seeking the court's reconsideration of the decision. Moreover, a temporary 'stay' on the enforcement of the decision would, for the government, assuage the concerns associated with disbanding Salwa Judum and discharging the SPOs immediately – 'we will be spared the need to immediately give the marching order to SPOs', one senior official noted. Gradually, however, its strategy grew more sophisticated. Rather than proceeding with challenging and reviewing the Supreme Court's decision, the state government chose to accept and sidestep it instead.

The Chhattisgarh government filed an affidavit claiming that it had disbanded Salwa Judum and no longer used SPOs in counter-insurgency operations. Strictly speaking, this was true – or at least clever enough to avoid the charge of open defiance of the court's decision. However, it was highly misleading. Shortly after the judgement, a law was enacted establishing a Chhattisgarh Auxiliary Armed Police Force, to 'aid and assist the security forces' in maintaining order and combating Naxal violence. This sounded strikingly similar to what the SPOs did before the Supreme Court's decision. The SPOs were appointed as members of this new force with effect from the date of the court's decision. This meant that the SPOs effectively retained their jobs following the decision. The state government's public justification for this new force was that its members were better paid, better trained and better equipped than SPOs – all of which was true, but which ignored the spirit of the court's concern with establishing a parallel force to undertake combat operations otherwise assigned to paramilitary forces. As Nandini Sundar said in an interview, 'The state government simply renamed the SPOs as Armed Auxiliary Forces with effect from the date of the judgement and gave them better guns.'

Nandini Sundar, Ramchandra Guha and E A S Sarma were alive to the state government's attempt to sidestep the decision. They filed contempt petitions in the Supreme Court, claiming the state government had complied with the decision only in name. This set off a cat-and-mouse game in which while the contempt petition awaited a full hearing, Salwa Judum regularly changed form over the years. The various avatars assumed by Salwa Judum since the Supreme Court's decision included the Jan Jagran Abhiyan, Vikas Sangharsh Samiti, Samajik Ekta Manch and Nagrik Ekta Manch. All the while, the Supreme Court failed to implement the spirit of its decision, while the state government continued to proclaim formal compliance.

It is hard to diagnose the reasons for the colossal failure to meaningfully implement the Supreme Court's decision. Some scholars have criticized the court for framing its decision too narrowly, by focusing too much on the education, training and remuneration of SPOs rather than the inherent unconstitutionality of establishing an armed civilian movement. This criticism is somewhat harsh, as there was enough in the court's decision to suggest that its apprehensions were categorical rather than narrow. Take, for example, paragraph 75, where the court ordered the state government to take 'all appropriate measures to prevent the operation of any group . . . that in any manner or form seek to take law into private hands'. The court's greater failing, however, was to allow the contempt petitions to linger on even as Salwa Judum took on different avatars.

The state government, on the other hand, executed perfectly the strategy of minimalistic, formal compliance with the court's decision whilst acting against its substantive content. Civil society, and in particular the mainstream media, did not provide it anywhere near the kind of coverage that the most politically salient cases of the time – such as the 2G spectrum case and the Bhullar death penalty case – received. More than ten years, seventy hearings and one significant decision later, the court struggled to keep pace with the shifting manifestations of Salwa Judum.

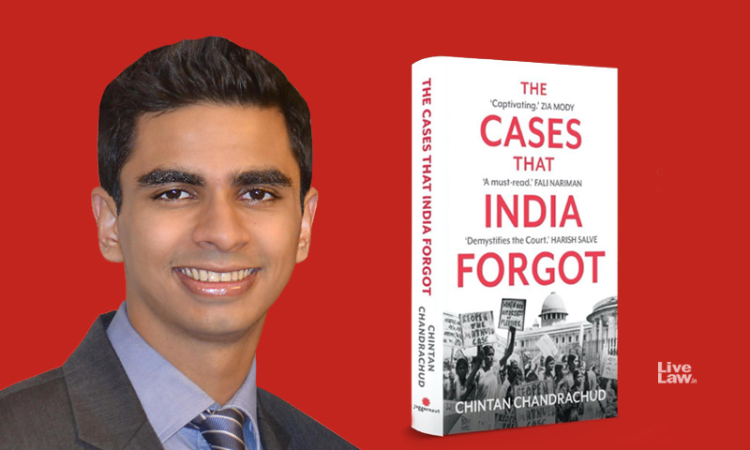

(This is an extract from "The Cases that India Forgot" by Chintan Chandrachud. The extract has been published with the permission of the author.)

Views Are Personal Only.