Ex-CJI Gogoi's Rajya Sabha Nomination Disturbs Public Faith In Judiciary

Manu Sebastian

17 March 2020 9:20 AM IST

"One cannot expect justice from those who, on the verge of retirement, throng the corridors of power looking for post retiral sinecures", Justice Deepak Gupta in Rojer Mathew Case (CB)

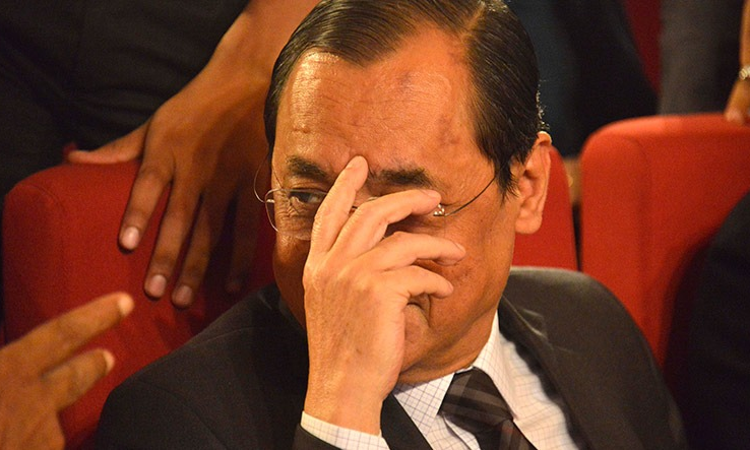

In a move that raises fresh questions about the debilitating nature of judicial independence, the Central Government on Monday nominated former Chief Justice of India Ranjan Gogoi - arguably the most controversial CJI of recent times - as a member of the Rajya Sabha within four months of his retirement on November 17 last year.

This is not the first time that a former CJI is becoming a member of Rajya Sabha, as ex-CJI Justice Ranganath Mishra was elected to the Upper House on Congress ticket in 1998 seven years after his retirement. Justice Baharul Islam had resigned as a Supreme Court judge in 1983 to contest elections to Rajya Sabha on Congress ticket, and became an RS member that year itself.

But the Centre nominating a former CJI as an RS member under Article 80(3) of the Constitution, soon after his retirement, is unprecedented.

The pitfalls of immediate post-retirement appointments given to judges are easily conceivable and widely discussed. Former Union Minister and Senior Advocate Arun Jaitley once bluntly stated that "pre-retirement judgments are influenced by a desire for a post-retirement job".

"My suggestion is that for two years after retirement, there should be a gap (before the appointment), because otherwise, the government can directly or indirectly influence the courts and the dream to have an independent, impartial and fair judiciary in the country would never actualise," Jaitley had said in the capacity of Leader of Opposition of Rajya Sabha in 2012.

Immediate Post-Retirement Appointment of Judges : Mutual Bonhomie between Executive And Judiciary?

But this word of caution, also echoed by several former CJIs like Justices R M Lodha, T S Thakur, Kapadia etc., has never been heeded to in actual practice, as can be seen from several appointments such as that of Justice R K Agrawal as NCDRC President and Justice A K Goel as NGT Chairperson . However in these cases, there was at least a defense of statutory mandate as the relevant laws required these posts to be occupied by retired judges (though this defense is no satisfactory explanation for granting immediate post-retirement benefit). What makes the appointment of Justice Gogoi so brazen is that there is no such statutory compulsion or expediency which necessitates his nomination to the Rajya Sabha within a short-span of his retirement.

CJI Gogoi : A Term Of Misses And Omissions

It is here the controversial tenure of CJI Gogoi comes to focus, during which the Apex Court, through its actions and inactions, protected and furthered the interests of the Executive on several instances. The nearly infructuous verdict in the CBI-Alok Verma case; the shaky clean chit given to Centre in the Rafale scam; the indefinite delaying of the hearing in the case challenging electoral bonds scheme; the steely reluctance shown in interrogating the government in the Kashmir habeas matters; the Ayodhya verdict with its highly questionable legal soundness - in these cases, the Supreme Court seemed to be in sync with the agenda of the State. Justice Gogoi played a major role in engineering the Assam-NRC fiasco, and he felt no conflict of interest in judicially overseeing the process, despite being personally invested in the matter. Even as the head of the SC Collegium, Justice Gogoi gave out the impression of playing to the tunes of the Centre, as indicated by the manner in which Justice Kureshi's transfer and elevation was handled.

During the term of CJI Gogoi, we saw the Supreme Court looking the other way when citizens complained of violation of basic rights. We saw the executive getting away with its actions unquestioned on several instances (more detailed in this article "CJI Gogoi - A Term of Misses and Omissions"). Justice Gogoi demitted office as the pale shadow of the man who participated in the unprecedented judges' press conference of January 2018, and who enthralled everyone in his famous Goenka memorial lecture with his exhortations to protect constitutional rights.

Press Conference, Goenka Lecture, Sealed Covers, Collegium Decisions And More.

An inescapable irony in this development is that Justice Gogoi had headed the Constitution Bench which delivered the judgment in the Rojer Mathew case, where the Court expressed concerns about the impact of post-retirement appointments on judicial independence. The Court in this case struck down the provision in Tribunal Rules which enabled re-appointment of Tribunal Members after retirement by observing that "the provision for reappointment would undermine the independence of the member who would presumably be constrained to decide matters in a manner that would ensure their reappointment".

Justice Gogoi observed in the judgment that "the discretion accorded to the Central or State Government to reappoint members after retirement from one Tribunal to another discourages public faith in justice dispensation system which is akin to loss of one of the key limbs of the sovereign" and added that it "increases interference by the Executive jeopardising the independence of judiciary".

Though these observations were made in the context of appointment of members of Tribunals, as a principle concerning judicial independence, they are relevant with respect to Constitutional Courts as well.

Also relevant are some observations made by Justice Deepak Gupta in his concurring judgment in the said case :

"There may be some posts which require retired judges to be appointed such as Lokpal, Lokayukta, Chairpersons of the Human Rights Commission, Chairman of the Law Commission of India, etc. But this should not become a matter of routine especially when the appointments are being made by the executive. If the administration makes appointments and judges, serving or newly retired judges, are under consideration for such posts then the independence of the judiciary is likely to be compromised. The public of this country still reposes great faith in the judiciary. That faith will be eroded in case it is felt that the appointments are made for extraneous reasons. Most judges live up to the expectations of the high standards of integrity and propriety expected from them but we cannot shut our eyes to the harsh reality that there are a few black sheep. One cannot expect justice from those who, on the verge of retirement, throng the corridors of power looking for post retiral sinecures"

In these circumstances, one cannot be faulted for wondering if the Rajya Sabha nomination is a 'quid pro quo' of sorts.

Questions about suitability

Apart from institutional concerns about judicial independence, the present appointment also raises questions regarding the suitability of the individual to the post.

It is well-etched in public memory that Justice Gogoi was alleged of sexually harassing a staff of SC, and that he had used the powers of his office to stall and bulldoze a proper probe into the matter.

Before the woman came out in public with sexual harassment allegations, she was terminated from service on flimsy grounds, in a manner so disproportionate and unjust.

Why Dismissal Of SC Staff Who Alleged Sexual Harassment By CJI Is Disproportionate?

Her husband and family members had also to face vindictive actions in the form of suspension from service and criminal cases.

When the woman's allegations were reported by media in April, the first response of Justice Gogoi was to convene an urgent sitting on a Saturday and launch ad hominem attacks on the accuser, in her absence. CJI Gogoi characterized the allegation as an attempt to "deactivate judiciary", and complained about being served a raw deal after several years of selfless service to judiciary.

"More after 20 years of selfless service. It is unbelievable ...With a bank balance of 6,80,000 that is in my bank account. This is my total asset. When I started as a judge, I had much hope. On the verge of retirement I have 6 lakhs. This is the reward CJI gets after 20 years , a bank balance of 680,000", he exclaimed during that extraordinary proceeding, which was curiously titled "In Re : Matter of Great Public Importance Touching Upon The Independence Of Judiciary Mentioned By Shri Tushar Mehta, Solicitor General of India" .

The zealous defence advanced for Justice Gogoi by the top law officers of the Centre - the Attorney General and the Solicitor General- should have been sufficient indication for observers regarding the mutual bonhomie between the judiciary and the executive.

Then emerged a host of counter-allegations against the woman that her complaint was a part of "larger conspiracy" against the CJI hatched by a gang of "fixers and disgruntled SC employees". A special bench of the SC constituted a one-member commission of former SC judge Justice A K Patnaik to probe the allegations of larger conspiracy, after holding day to day hearing on urgent basis.

Meanwhile, the in-house panel of the SC, which conducted probe without any adherence to norms of transparency, absolved Justice Gogoi of the charges, for reasons we would never know. The woman had decided not to participate in the proceedings, questioning the procedure adopted by it.

What is surprising is a subsequent development, which happened after the retirement of Justice Gogoi. In a move that gives post-facto credibility to her complaint, and demolishes the base of "larger conspiracy" allegations made against her, the woman who raised the sexual harassment allegations was reinstated into SC service. Though Justice Patnaik commission submitted its report before SC in September last year, its contents are not made public, and no action has ensued on the same. The present passivity shown by the Court in this "Matter of Great Public Importance Touching Upon The Independence Of Judiciary" is highly surprising. These circumstances certainly shake the clean chit given to Justice Gogoi in the case.

The larger question of morality here is should a person with such a cloud over character be appointed to an eminent post in the House of Elders? Even though Article 80(3) does not make an express mention of 'good character' as a condition for nomination, it will be against the principles of constitutional morality and doctrine of constitutional implications to argue that such a requirement is not needed.

When former CJI P Sathasivam was appointed as Governor of Kerala in 2014 soon after his retirement, it had raised several eyebrows. But the degree of brazenness in Justice Gogoi's appointment surpasses all previous cases. To say the least, the swift jump from one branch to another does not look graceful.

Before parting, it is pertinent to refer to an observation made by SC in the 'master of roster case' :

"The faith of the people is the bed-rock on which the edifice of judicial review and efficacy of the adjudication are founded. Erosion of credibility of the judiciary, in the public mind, for whatever reasons, is greatest threat to the independence of the judiciary".