- Home

- /

- Book Reviews

- /

- From Doon to Tihar: Notes from...

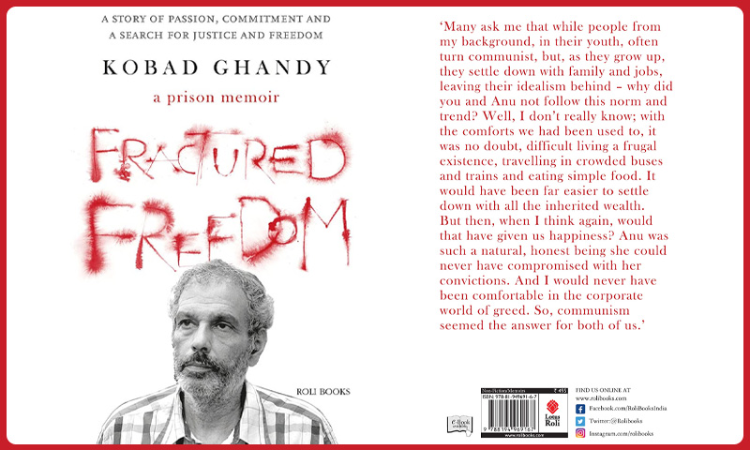

From Doon to Tihar: Notes from Fractured Freedom

Shaileshwar Yadav

29 Aug 2021 10:54 AM IST

On 17 September 2009, a senior citizen of nearly 62 years with multiple health issues was dragged inside an SUV at a busy bus stop in Delhi. The 'abduction' or an arrest, as Kobad Ghandy writes in his prison memoir – Fractured Freedom was done by none other than the Andhra Pradesh Intelligence Bureau. Little Kobad knew that this arrest on his journey from Mumbai to Delhi for...

Next Story