The Satanic Verses – A 36 Year Ban In India Based On A Notification Nowhere To Be Found

Katyayani Suhrud

8 Jan 2025 4:34 PM IST

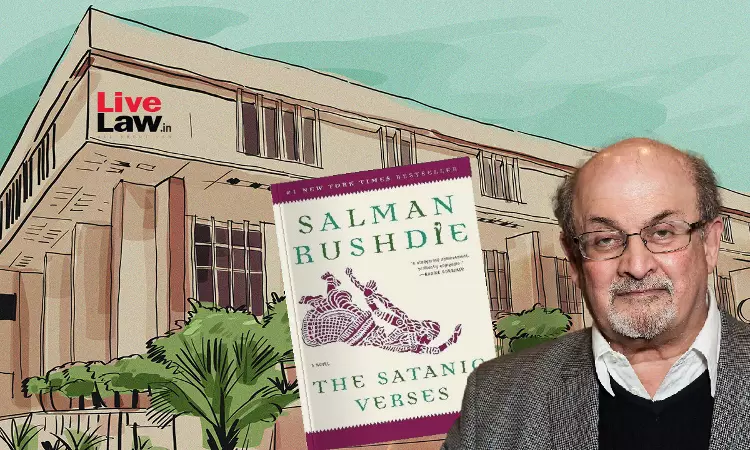

On October 5, 1988, vide Custom Notification no. 405/12/88-CUSIII, the import of The Satanic Verses, a novel by the author Salman Rushdie, was banned[1]. To give a brief background, Rushdie then was and continues to be one of the most celebrated authors of the 20th and 21st centuries. The Satanic Verses was his fourth novel, published seven years after his epic Midnight's Children. It was perceived as a book about Islam, derogatory and blasphemous towards the Prophet. It is pertinent to point out that nearly every person, head of State or organisation that condemned the book and its author admitted to never having read it. In many parts of the Islamic and the supposedly secular world, the book was burned, banned, and Rushdie's effigies set on fire by people who had not thought it necessary to read what they were burning[2]. Iran's Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa against Rushdie, who was forced to go underground for a decade because of the threats to his life that followed. The Satanic Verses changed the course of Rushdie's life and the course of how the value of freedom of speech and expression was treated around the world.

One of the first countries to ban the book was the country of his birth and of his novels – India. The Rajiv Gandhi government imposed, of all things, a customs ban on the import of the book. Noting this oddity, in an article titled “My Book Speaks for Itself”[3], Rushdie wrote in February, 1989, “Many people around the world will find it strange that it is the Finance Ministry that gets to decide what Indian readers may or may not read.” The Indian state thus took recourse to a customs technicality which was not the real issue, instead of banning the book for the reasons that it actually feared, which echoed what the colonial government had done with M.K. Gandhi's Hind Swaraj in Gujarati. The ban on The Satanic Verses was a ban on its import, imposed through Section 11 of the Indian Customs Act, 1962, which deals with the power to prohibit import or export of goods under heads like maintaining the security of India, maintaining public order and standards of decency or morality, preventing dissemination of documents which may affect national prestige or friendly relations with a foreign State, etc., but it was commonly understood to be a ban on the book in general – on its possession, publication and distribution.

36 years and 1 month later, the ban was lifted on November 5, 2024 by an order of the Delhi High Court[4]. The three page order gives a singular reason for lifting the ban – the notification banning the book was nowhere to be found, and would thus be presumed not to exist. If it is presumed that no such notification exists, the court cannot examine its validity and the Writ Petition came to be disposed of.

Two things about the manner in which the ban was lifted stand out: One, it took 31 years for the ban to be challenged in a court of law. This was not a ban on a relatively unknown book, written by an author of little consequence. It would not be an exaggeration to say that what happened to The Satanic Verses has happened to very few books in the last century. The controversy surrounding it and Rushdie, and the recent nearly successful attempt on Rushdie's life may well place The Satanic Verses in the same category as the likes of Lady Chatterley's Lover[5]. The furore surrounding it was loud, violent, omnipresent, and unlawful. Additionally, this was a ban in a country like India, which has a long and (mostly) victorious history of challenging bans on creative freedom in court. The ban attracted a lot of attention, with the author writing an open letter to then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, telling him that this was no way for a free society to behave[6]. Leading newspapers like the Indian Express and the Hindu derided it, fundamentalist leaders lauded it – all this to say that taking notice of the ban was inescapable for large swathes of India. And yet, nobody came to court for 31 years.

It is all the more surprising because Indian courts have, by and large, stood for freedom and against censorship. To give a few well known examples, Jaswant Singh's book on Jinnah[7], more than one Anand Patwardhan film[8], and most recently the Netflix film Maharaj[9] – have all been supported by various courts. This history gives us more reason to believe that if we approach a court challenging a ban, the resultant judgment is likely to be one for freedom. Given this hope-inducing record, why it took one of us three decades to knock on a court's door is a mystery.

Two, the manner in which the ban came to be lifted sounds like it was a scene taken out of one of Rushdie's novels – absurd, hard to believe, tragicomic, and yet a reaffirming of one's faith in the courts of this country. The banning of this book invoked one of the grand narratives of the modern world – freedom. The ban was about freedom to write, freedom to read, freedom to choose what is/is not offensive, all of which can be broadly categorised as freedom of thought, speech and expression. Therefore, when a ban which carries the weight of this lost freedom is brought to court, it is reasonable to assume that the judgment, whether pronounced for or against freedom, will at least, at the very minimum, be about (if not primarily then tangentially), that freedom. Instead, what we have is a three page order, which in its seven paragraphs does not feel the need to even mention the word freedom, much less deal with it extensively.

The ban on The Satanic Verses was lifted on the basis of legal first principle – A document which is relied upon must be produced. It is a principle so fundamental that no lawyer would think of making an argument without material to substantiate it. Notions of proof, of proving something beyond reasonable doubt, and of the onus of proof form the bedrock of the legal system. Courts aren't the place to make educated guesses or rely on public memory to state that a ban does indeed exist. It is the notification which should have been published in the official gazette which matters, legally. Hardly anyone who has followed this ban would have thought that the argument would begin and end with the customs notification, without venturing into the murkier space of offensiveness, outrage, religion, public morality, and freedom.

It would have been understandable to assume that if and when this ban was challenged, it would culminate in a thumping Supreme Court judgment with lengthy discussions on the need to protect freedom or the reasons to curtail it, with substantial media attention throughout the proceedings. The short, technical, thoroughly legal, almost stealthy lifting of this controversial ban is a pleasant surprise. Equally silently, Rushdie's book has returned to Indian bookshops after 36 years, giving it at long last what he calls the ordinary life of a book. Rushdie wrote through one of his characters in his 2005 novel Shalimar the Clown, “Freedom is not a tea party, India. Freedom is a war.” However, this long awaited freedom may well have been a tea party. The Delhi High Court found a wonderfully technical ground, in a way that only a legal mind can, to free both writer and readers from a ban without going to war. It is very welcome.

However, Indian courts in the past have had debates on where the line for when freedom ends and reasonable restrictions begin should be drawn, and whether it should be drawn at all. It is good for any free society to understand anew its ideas of freedom every now and then by allowing vociferous debate and conversation to take place, of the kind we saw in K.S Puttaswamy v. Union of India[10]. It contributes to the health of that freedom and brings ideas, both celebrated and taboo to the surface. But for bureaucratic ineptitude that did not let the challenge to the ban move beyond the customs notification, the ban on The Satanic Verses would have been an opportunity for civil society and courts to come together to deliberate on what it means to be free. While the order of the Delhi High Court is a victory for freedom no doubt, it is not a victory because freedom was victorious. It is a victory because a piece of paper could not be found. Uddyam Mukherjee, the lawyer for the petitioner who challenged the ban said, “We can't call it a freedom of expression judgment. The judgment stemmed from the bureaucracy's inefficiency in producing the document.”[11] That, for the debate that was possible and could not happen, is an opportunity lost.

Indian courts have often made the most of this opportunity. In S. Tamilselvan v. The Govt. of Tamil Nadu[12], then Chief Justice of the Madras High Court Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul wrote, “If you do not like a book, simply close it. The answer is not its ban… Art is often provocative and is meant not for everyone, nor does it compel the whole society to see it. The choice is left with the viewer. Merely because a group of people feel agitated about it cannot give them a license to vent their views in a hostile manner, and the State cannot plead its inability to handle the problem of a hostile audience…Let the author be resurrected to what he is best at. Write.”

Similar conversations have been had in Ranjit Udeshi v. State of Maharashtra[13], Baragur Ramachandrappa v. State of Karnataka[14], and N. Radhakrishnan v. Union of India[15] to name a few. Even when judgments have limited freedom in the name of public decency, religious sentiments, public order and morality, they have by and large engaged with the idea of freedom. “…the Supreme Courts – and all courts – must continue to be the guardian of the right to express, to speak, to think.”[16].

Where we choose to draw the line that limits freedom and whether we choose to draw it at all is a classical question with no definite answer. Being able to challenge and misplace this line is an inalienable right of any creative expression. In order for novelists to write, every once in a while a time comes when judgments too must be written to sustain and bolster this freedom. The Satanic Verses is back where it belongs – on a shelf of a bookshop. As the last sentence of his novel Victory City, Rushdie writes, “Words are the only victors.”

Author is a lawyer practicing in the Supreme Court of India. Views Are Personal.

Thapliyal, N. (2024). Delhi High Court Says Notification Banning Import of Salman Rushdie's 'The Satanic Verses' Doesn't Exist As Authorities Fail To Trace It. Live Law. https://www.livelaw.in/high-court/delhi-high-court/delhi-high-court-salman-rushdie-book-the-satanic-verses-ban-import-274509 ↑

Wright, R. (2022). Ayatollah Khomeini Never Read Salman Rushdie's Book. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/ayatollah-khomeini-never-read-salman-rushdies-book ↑

Rushdie, S. (1989). My Book Speaks For Itself. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1989/02/17/opinion/my-book-speaks-for-itself.html ↑

Thapliyal, N. (2024). Delhi High Court Says Notification Banning Import of Salman Rushdie's 'The Satanic Verses' Doesn't Exist As Authorities Fail To Trace It. Live Law. https://www.livelaw.in/high-court/delhi-high-court/delhi-high-court-salman-rushdie-book-the-satanic-verses-ban-import-274509 ↑

Kenny, N. (2024). 'It's rather different from selling an ordinary book': How Lady Chatterley's Lover was banned - and became a bestseller. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20241031-how-lady-chatterleys-lover-was-banned-and-became-a-bestseller#:~:text=In History looks at the,writing considered indecent and immoral. ↑

Rushdie, S. (1989). My Book Speaks For Itself. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1989/02/17/opinion/my-book-speaks-for-itself.html ↑

Dasgupta, M. (2009). Gujarat Ban on Jaswant book struck down. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/news/Gujarat-ban-on-Jaswant-book-struck-down/article16879233.ece ↑

Chakraborty, A. (2020). India's Leading Documentary Filmmaker Has a Warning. The New York Times Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/01/magazine/india-documentary-anand-patwardhan.html ↑

PTI. (2024). Gujarat HC lifts stay on release of 'Maharaj', debut film of Aamir Khan's son. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/entertainment/movies/gujarat-hc-lifts-stay-on-release-of-maharaj-debut-film-of-aamir-khans-son/article68316320.ece ↑

(2017) 10 SCC 1 ↑

Kim.V & Pragati.K.B. (2024). The Saviour of 'Satanic Verses' in India: Bureaucratic Ineptitude. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/11/08/world/asia/india-salman-rushdie-satanic-verses-book-ban.html ↑

2016 3 L.W. ↑

1964 SCC Online SC 52 ↑

(2007) 5 SCC 11 ↑

(2018) 9 SCC 725 ↑

Tripathi, S. (2024). “Appealing to prurient interests”: Book bans, the courts, the mob. Supreme Court. Observer. https://www.scobserver.in/75-years-of-sc/appealing-to-prurient-interests-book-bans-the-courts-the-mob/ ↑