The Jadhav Case & Jurisdiction Of The International Court Of Justice

Vijay Purohit

29 May 2017 1:24 PM IST

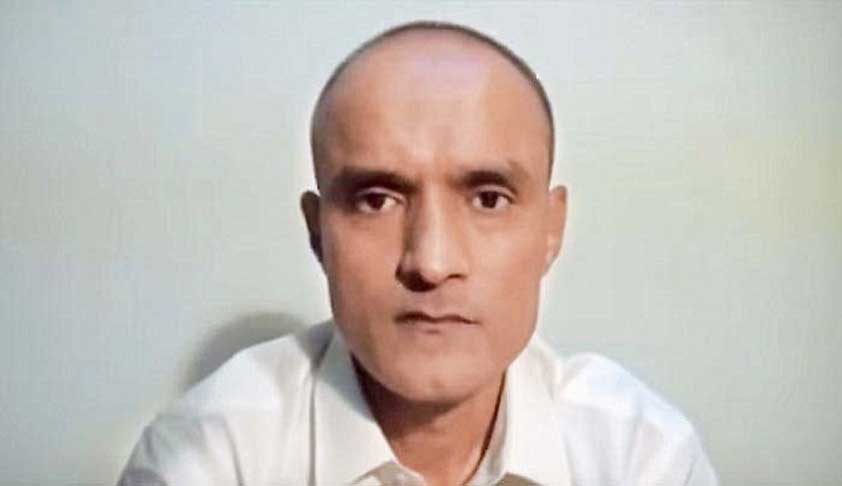

The recent case of Kulbhushan Jadhav has got a lot of people talking about International Law and the International Court of Justice (“ICJ” or the “World Court”). While a majority of the views expressed in this regard are essentially based on the media reports on the case, there are a lot of genuine questions & queries on the functioning of the court. The issue that has gained a lot of coverage is, Pakistan’s plea of the ICJ not having jurisdiction to entertain India’s application. It was widely believed (in hindsight of course) that the plea of jurisdiction taken by Pakistan was weak.

This article aims at having a bird’s eye view on the jurisdiction of the Court. Those of us who were inclined towards mooting during our law school days, particularly in the realm of international law, are somewhat aware about the existing legal fiction in this domain. We, at the Gujarat National Law University (GNLU) were extremely fortunate to have been taught by Late Prof. Dr. V. S Mani, who was considered as one of the finest authorities on the subject and his innumerable writings on various aspects of International Law form an integral part of the existing literature on the subject. Dr. Mani also represented & assisted state parties before the ICJ on multiple occasions.

The ICJ as we see today, was preceded by the Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ), under the regime of the League of Nations. With the formation of the United Nations in 1945, the ICJ came to be formed as the judicial organ of the UN. The Court is governed by the Statute of the ICJ (“the Statute”) and the rules framed thereunder. Naturally, the member states of the UN are automatic parties to the Statute. Subject to certain conditions, States who are not party to the UN Charter may also become parties to the Statute(Article 93(2) of the UN Charter). Under exceptional circumstances, the Court may be accessible to States who are not a party to the Statute, as decided in the Security Council Resolution 9(1946) of 15 October 1946. The judgments of the PCIJ & ICJ, called the Reports, serve as one of the sources of law for the Court to decide cases. Let us independently & succinctly examine the existing provisions & precedents pertaining to the jurisdiction of the Court.

Article 36 of the Statute

Article 36 of the Statute (Chapter-II, Competence of the Court), lays down the jurisdiction of the Court as under:

- The jurisdiction of the Court comprises all cases which the parties refer to it and all matters specially provided for in the Charter of the United Nations or in treaties and conventions in force.

- The states parties to the present Statute may at any time declare that they recognize as compulsory ipso facto and without special agreement, in relation to any other state accepting the same obligation, the jurisdiction of the Court in all legal disputes concerning:

- the interpretation of a treaty;

- any question of international law;

- the existence of any fact which, if established, would constitute a breach of an international obligation;

- the nature or extent of the reparation to be made for the breach of an international obligation.

- The declarations referred to above may be made unconditionally or on condition of reciprocity on the part of several or certain states, or for a certain time.

- Such declarations shall be deposited with the Secretary-General of the United Nations, who shall transmit copies thereof to the parties to the Statute and to the Registrar of the Court.

- Declarations made under Article 36 of the Statute of the Permanent Court of International Justice and which are still in force shall be deemed, as between the parties to the present Statute, to be acceptances of the compulsory jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice

- In the event of a dispute as to whether the Court has jurisdiction, the matter shall be settled by the decision of the Court.

Article 36(2) above, provides for the compulsory jurisdiction of the Court, which means that a State that has recognized the compulsory jurisdiction of the Court has in principle, the right to bring any one or more other State which has accepted the same obligation before the Court by filing an application instituting proceedings with the Court, and, conversely, it has undertaken to appear before the Court should proceedings be instituted against it by one or more such other States. India and Pakistan both, have by way of respective declarations, recognized the compulsory jurisdiction of the Court (India recognized the compulsory jurisdiction of the Court by declaration dated 18 September 1974 and Pakistan vide declarations dated 12 September 1960 & 29 March 2017). It is however interesting to note that parties recognize compulsory jurisdiction of the Court with reservations. Therefore, Article 36(2) is also popularly termed as “Optional Clause” conferring jurisdiction on the Court.

However, the Optional Clause does not stand by itself. It is an integral part of the Statute and adherence to the Optional Clause means adherence to the whole of the Statute. It does not appear to be open to states in their unilateral declarations to make their acceptance of jurisdiction conditional upon non-application of constitutional provisions of the Court's Statute. The Court is required, both by Article 92 of the Charter and Article I of the Statute, to function in accordance with the Statute. For instance, the declarations signed by India & Pakistan respectively, list a number of exceptions, which are excluded from the ambit of compulsory jurisdiction that both the countries have conferred on the ICJ.

Another important facet of jurisdiction of the Court is the “reciprocity” principle with respect to the reservations made by state parties. This principle is well established in the jurisprudence of the Court. In the Republic of Nicaragua v. the United States of America (“Nicaragua Case”) [Case Concerning Military and Paramilitary Activities in and Against Nicaragua, 1986 ICJ 1], the World Court observed that:

The notion of reciprocity is concerned with the scope and substance of the commitments entered into, including reservations, and not with the formal conditions of their creation, duration or extinction. It appears clearly that reciprocity cannot be invoked in order to excuse departure from the terms of a State’s own declaration whatever its scope, limitations or conditions,

In the United Kingdom vs. Norway (“Fisheries Case”), the Court held that any reservation made by parties qua the question of determination of dispute to be falling within the municipal jurisdiction contrary to any express provision of the Statute has to be declared invalid.

The vigor of Article 36(2) therefore, is not really reflective of the term “compulsory jurisdiction”.

Judge Hudson remarks:

The term "compulsory jurisdiction" employed in the Statute is in some degree misleading. It means merely that a State which has accepted it is subject to the jurisdiction of the Court without the necessity of giving its consent in the particular case. In such a situation the Court .will be competent to give a judgment whether the respondent "is present or absent", and the judgment will be binding on all States parties to the case. The term carries no implication as to the enforcement of judgment.

The Jadhav Case: Prima Facie Jurisdiction

As far as the Jadhav Case is concerned, the ICJ held that it has prima facie jurisdiction as per Article I of the Optional Protocol to the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations. The Court also observed that the relief claim by India has a link to the rights enshrined in Article 36(1) of the Vienna Convention. Therefore, on the basis of a prima facie case made out by India vis-à-vis jurisdiction & substantial rights which were likely to get prejudiced if the interim measures were not to be granted, the Court passed an order granting interim measures in favor of India. Pakistan on the other hand contended that the in view of the reservations in the declaration made by both India & Pakistan as also the Agreement on Consular Relations on 21 May 2008 between India & Pakistan (“Agreement of 2008”), the Court is bereft of jurisdiction.

While the court did observe that it has prima facie jurisdiction for the purposes of granting interim measures, it is an issue which could still be contested when the case is argued on merits.

Pakistan has argued, and can further argue that in view of the reservations made by India with respect to disputes between two members of the Commonwealth as also Pakistan’s own declaration qua its internal security are valid reservations within the meaning of Article 36(2) so as to oust the jurisdiction of the Court.

While on a prima facie basis, the Court has held that the bilateral agreement between India & Pakistan would not limit its jurisdiction, its jurisdiction in substance, i.e., its competence to adjudicate on the substantial dispute at hand between the parties is something which it will need to examine in view of the decided cases.

Probable arguments on preliminary objections & merits of the case

India can potentially develop the argument that the bilateral agreement between India and Pakistan entered into in 2008 as well as the reservations contained in the declarations made by Indian & Pakistan respectively, which the Court has not considered as impediments while deciding prima facie jurisdiction, cannot be construed to be valid reservations within the meaning of Article 36 and further, in light of the Fisheries Case, cannot oust the jurisdiction of the ICJ. In any event it is a question which is the Court itself is competent to decide under Article 36(6).

As far as the Agreement of 2008 is concerned, India has recourse to the principle laid down in the Corfu Channel Case, where the Court observed that:

Furthermore, there is nothing to prevent the acceptance of jurisdiction, as in the present case, from being effected by two separate and successive acts, instead of jointly and beforehand by special agreement. As the Permanent Court of International Justice has said in its Judgment No. 12 of April 26th, 1928, page 23: "The acceptance by a State of the Court's Jurisdiction in a particular case is· not, under the Statute, subordinated to the observance of certain forms, such as, for instance, the previous conclusion of a special agreement. "

Of course the provision that the Court should decline jurisdiction in matters which are solely within the domestic jurisdiction of states, does not prevent the expansion of the sphere of international regulation and 'corresponding contraction of the sphere of the exclusive jurisdiction of states. As the Permanent Court of International Justice said in a Classical statement in the Tunis-Morocco Nationality Decrees case: "The question whether a certain matter is or is not solely within the jurisdiction of a State.is an essentially relative question;·it depends upon the development of international relations."

Existence of a dispute

Another point that was argued and is likely to be argued further in the Jadhav Case is that of existence of a dispute.

In the Chorzow Factory Case, the PCIJ observed that:

It would no doubt be desirable that a state should not proceed to take as serious a step as summoning another state to appear before the Court without having previously, within reasonable limits, endeavored to make it quite clear that a difference of views is in question which has not been capable of being otherwise overcome. But, in view of the wording of the article, the Court considers that it cannot require that the dispute should have manifested itself in a formal way; according to the Court's view, it should be sufficient if the two governments have in fact shown themselves as having opposite views.

Pakistan has contended that it had written to India in relation to the question of granting consular access to Jadhav & the fact of his arrest. India, on the other hand has disputed Pakistan’s assertions and has taken a specific plea that Pakistan has denied consular access to Jadhav. This means that there obviously exists a difference of opinion in so far as the two State Parties are concerned. Therefore, as rightly observed by the Court in its Order dated 18 May 2017 in the Jadhav case, the fact that there is a difference of opinion between the two State Parties, the Court has prima facie jurisdiction. On the basis of the existing jurisprudence on (a) the jurisdiction of the Court and (b) the nature of valid reservations that state parties can have while accepting compulsory jurisdiction of the Court, India might have a good case in establishing substantial jurisdiction of court, like it has while seeking interim measures.

On a different note, while the court granting interim measures is definitely a welcome move as far as India is concerned, what needs to be seen is Pakistan’s commitment in enforcing the interim measures as well as the judgment of the ICJ, which will be pronounced after hearing both the parties on merits. Pakistan has already moved the Court, post passing of the interim measures, to expedite the hearing of the case. At a political & diplomatic level, India has certainly scored an initial victory over Pakistan in successfully assailing Pakistan’s actions of non-adherence to international conventions. The road however, is a long one and India needs to devise its strategy carefully to convince the World Court on the merits of the case.

Vijay Purohit is a Senior Associate in MZM Legal (Mumbai).

[The opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of LiveLaw and LiveLaw does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same]