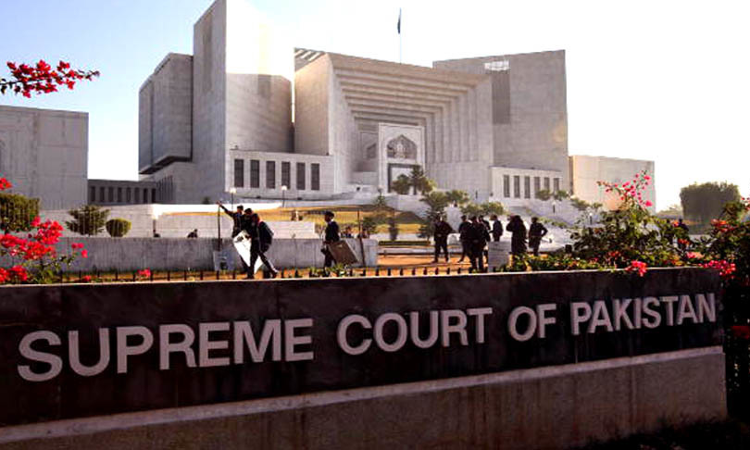

Supreme Court Of Pakistan Cites Indian Supreme Court's Judgment On Avoiding Gender Stereotypes

Gursimran Kaur Bakshi

29 March 2025 9:15 PM IST

Next Story

29 March 2025 9:15 PM IST

In a significant judgment for gender equality and continued recognition of women's legal rights, the Supreme Court of Pakistan overturned the judgment of a Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Service Tribunal, Peshawar, which held that "a married daughter becomes a liability of her husband" and therefore, not eligible for compassionate appointment of the deceased son/daughter quota. It held that the...