Supreme Court Delivers Split Verdict On Police Officers' Convictions In Decades-Old Custodial Death Case

Amisha Shrivastava

26 Sept 2024 9:57 AM IST

Next Story

26 Sept 2024 9:57 AM IST

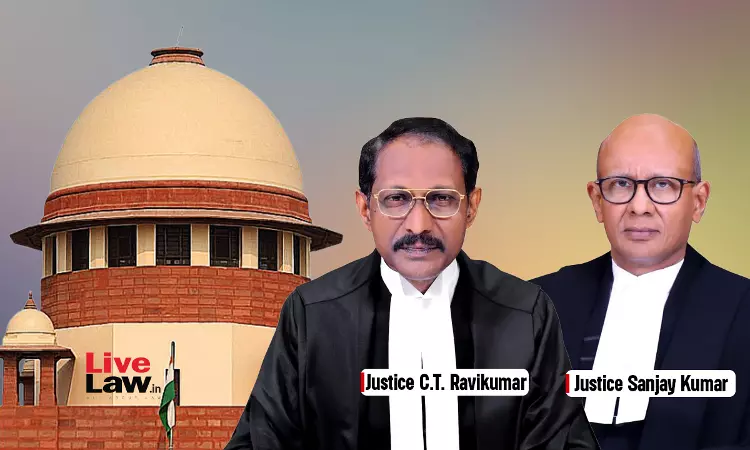

The Supreme Court has delivered a split verdict in an appeal by police officers convicted of culpable homicide not amounting to murder and other offences in a decades-old custodial death case for alleged torture and death of a man in police custody in December 1995.A bench of Justice CT Ravikumar and Justice Sanjay Kumar delivered a split verdict, particularly on the issue of conviction of...