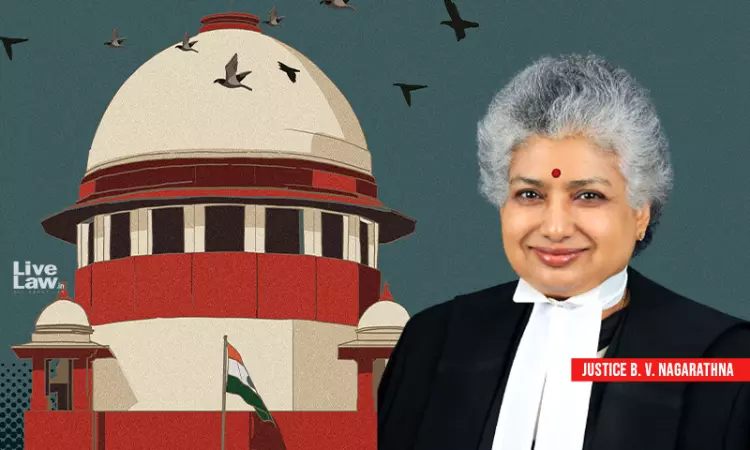

Royalty Is Tax, States Have No Right To Tax Mineral Rights : Justice Nagarathna's Dissent

Gursimran Kaur Bakshi

27 July 2024 11:19 AM IST

Next Story

27 July 2024 11:19 AM IST

The Supreme Court nine-judge bench headed by Chief Justice of India, Dr D.Y. Chandrachud and comprising Justices Hrishikesh Roy, Abhay Oka, BV Nagarathna, JB Pardiwala, Manoj Misra, Ujjal Bhuyan, SC Sharma and AG Masih, by 8:1, held that royalty charged by the Union Government under the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act, 1957 (MMDR Act) is not tax.The majority has held:...