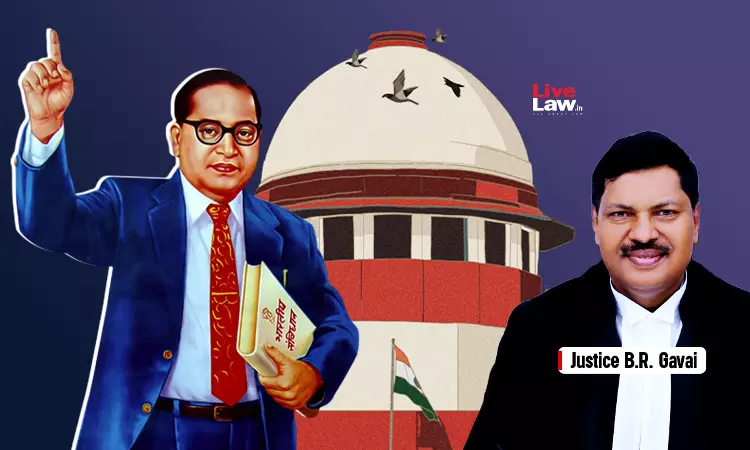

Exploring Dr. Ambedkar's Influence On Justice Gavai's Judgment In Caste Sub-Classification Case

Amisha Shrivastava

3 Aug 2024 10:05 AM IST

Next Story

3 Aug 2024 10:05 AM IST

In his judgment allowing sub-classification within Scheduled Castes (SCs), Justice BR Gavai of the Supreme Court drew extensively on the views of Dr. BR Ambedkar to address concerns and validate the decision. The judgment extensively references Ambedkar's thoughts on social justice, equality, and the upliftment of disadvantaged groups, using them as a foundation to support...