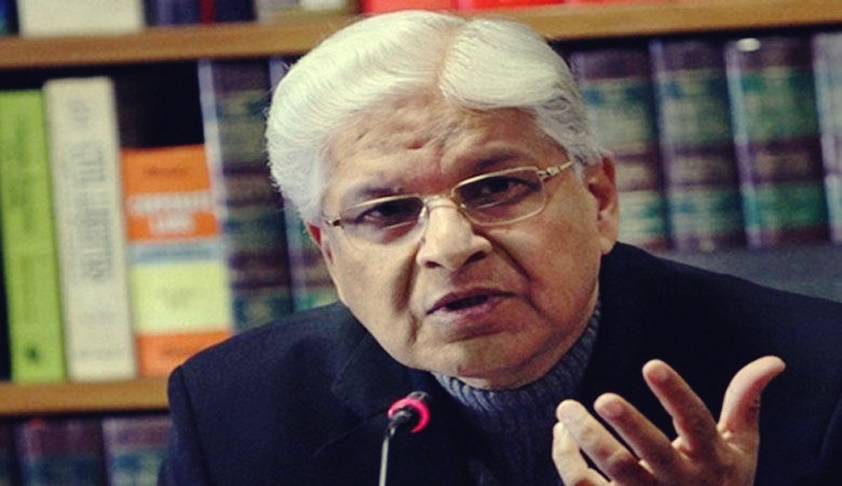

Security Concerns Are Often Cited To Defeat Minimum Humanitarian Morality: Dr. Ashwani Kumar, Former Law Minister Of India

Apoorva Mandhani

17 Nov 2017 10:09 AM IST

Dr. Ashwani Kumar seems to have done it all! He is an eminent legal counsel, political activist, author, policy-maker, a Union cabinet minister, and recipient of Japanese civilian honour ‘Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun’. While his achievements are many, it is his selfless battle for ratification of the United Nations Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment that has inspired many. Besides, he is espousing the case of dignity of old citizens in a PIL filed before the Supreme Court and is also arguing on behalf of the Rohingyas in the apex court.

In this interview, Dr. Kumar has an exclusive chat with LiveLaw over India's reluctance to enact an anti-torture law, which has been in the pipeline for decades.

LiveLaw: Dr. Kumar, you have been an ardent crusader for an anti-torture legislation. What inspired you to take up this specific cause and fight for it with all guns blazing? Further, the Law Commission of India recently recommended the implementation of the United Nations Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment. What do you think has stopped the government from ratifying it till now?

Dr. Kumar: As a politician from Punjab, I had the occasion to witness the plight of helpless people who were routinely detained and tortured in police custody often on the basis of suspicion and frivolous complaints, sometimes motivated by personal enmity and political vendetta. The scenario was particularly distressing during the days of terrorism when a senior police official candidly confessed that the only means available to the police to arrive at the truth and to identify the criminal was through third degree interrogation methods. Often, grave physical injury and unbearable mental trauma was the resultant consequence, not only for the person detained, but also for the near and dear ones of the detained and the tortured person. The situation continues to subsist and on one of my visits as a minister to Gurdaspur in Punjab, I came across a case where one young son of an old farmer was reportedly shot dead in an encounter by the police and the other was detained and being tortured in police custody. I was informed that if I did not intervene, the detained young man who was being beaten mercilessly would lose a limb, and possibly, his life. On inquiring from the senior police official concerned, I was told that the man was indeed being interrogated and I could assume the nature of interrogation, knowing the ground reality, in at least certain areas of the state. I understand that the young man was subsequently let off since no evidence was available against him. Such instances occur routinely in various states and physical and mental torture of same kind is an integral part of all custodial interrogation in our country.

In 2010, when I was member of the Rajya Sabha, a Select Committee of Parliament, under my chairmanship, was constituted to finalize a standalone anti-torture legislation which had so far defied political consensus since 1997, when India first signed the UN Convention against Torture. In the absence of political consensus, we were not able to pass suitable domestic legislation, which is a prerequisite for India to ratify the UN Convention. With the active support and comprehensive deliberations by members of the Select Committee representing all major political parties, we were able to finalize a comprehensive Anti-Torture Bill, 2010. The Select Committee’s recommended legislation was required to be placed in parliament, but was not done. I had requested the BJP government, in office since 2014, through several communications to pass the requisite legislation, so that India can ratify the UN Convention and avoid constant criticism in the international community for not showing regard for human rights of those in custody. The Union Government has avoided doing the same and has stated that there seems no need for a standalone anti-torture legislation.

Indian judiciary has a stellar record to be proud of as far as advancement of human rights are concerned. Several Supreme Court judgments have held that torture destroys human dignity, which is at the pinnacle in the hierarchy of human rights. Since I am personally committed to the preservation of human dignity in all its manifestations, I chose as a public interest petitioner to knock at the doors of the Supreme Court which is the ultimate custodian of the constitutional conscience.

I am delighted that the Law Commission has reaffirmed its consistent view in favour of a standalone legislation.

LiveLaw: The Government has, time and again, relied on the existing legal provisions as a defence for not enacting a fresh law for the purpose of preventing and punishing torture. Is this claim justified?

Dr. Kumar: The existing legal provisions in the Indian Penal Code are certainly not adequate to meet the tests of the UN Convention for a standalone legislation and this is the reason why we have failed to live up to the expectations of the international community and have failed to ratify the UN Convention and to show our commitment for the preservation of fundamental human freedom. I sincerely hope that the Law Commission's recommendation for a standalone legislation will be accepted and a purposive legal framework consistent with UN Convention Against Torture will be established to meet our constitutional and international treaty obligations.

LiveLaw: There have been claims that the anti-torture law has not been enacted in view of apprehensions from the security establishments, which feel that such a law will work against them. This is because techniques, which may qualify as inflicting torture, are regularly used during interrogations. What do you think about such assertions? There have also been apprehensions that such a law would force the administration to "act soft" on terrorist groups, especially in view of the country's strong stand against terrorism. Do you think such claims are justified?

Dr. Kumar: Security concerns are repeatedly projected to defeat even the minimum humanitarian morality. This approach is clearly impermissible in a country irrevocably committed to the advancement of fundamental human freedoms in an age of rights. I have no doubt that consistent with the Supreme Court's repeated affirmation of human dignity being the core human right, such arguments will not prevail.

It is possible to deal firmly with terrorists while remaining firm in our commitment to ensuring minimum human rights of all persons. The various UN declarations/resolutions including the Geneva Conventions are predicated on the premise that basic human rights including the right not to have one’s dignity infracted by torture, are to be guaranteed to all.

There are some gaps in the LCI draft and hopefully these will be addressed by the appropriate authorities.

LiveLaw: What are your thoughts on the draft Prevention of Torture Bill proposed by the Law Commission? The Prevention of Torture Bill, 2010, was severely condemned for the definition of 'torture' adopted by it. Do you think the definition recommended by the LCI Bill is acceptable? Also, what are your views on the explicit exclusion of ‘mere mental agony or tension arising due to coercion’ from the definition?

Dr. Kumar: We had given our utmost consideration to the definition of ‘torture’ in the 2016 Bill and to the best of my recollection, the 2010 Bill was generally welcomed by stakeholders. We had studied the laws in various countries and the inclusive definition of ‘torture’ in the 2010 Bill was drawn from the Philippines Law. A bare perusal of the hearings of the Select Committee that proposed the 2010 anti-torture Bill and the memoranda perused by us would demonstrate that the most serious consideration was given by parliamentarians acting across party lines, to the various aspects of the anti-torture Bill. A large number of experts, including jurists, were examined by the committees and their views recorded. I think that mental agony and tension through coercion are clearly a kind of torture, which most people cannot bear without serious consequences to their health.

LiveLaw: The 2010 Bill was also criticised for proposing dilution of the existing laws by imposing a time limit of six months and requiring prior government sanction for trying those accused of torture. This provision has been retained by the draft Bill proposed by the LCI. Do you think such requirement is justified? While the select committee had recommended a minimum punishment of 3 years and a minimum fine of Rs 1 lakh to be imposed on the person found guilty of torture, the draft LCI Bill does not impose any such conditions. Is it fair to say that this dimension needs to be remedied before the Bill sees the light of the day?

Dr. Kumar: A realistic time limit for prior sanction by the government will make the law efficacious and prevent frivolous prosecution of innocent officials. I believe that it is absolutely imperative to prescribe minimum punishment and fine so that those inclined to take the law into their own hands in torturing persons in custody are made aware that the punitive consequences of their action will be purposive and grave. I believe that this provision in the 2010 Bill should be retained in law.

LiveLaw: The LCI Bill also requires the act of torture to have the purpose of extorting a confession or any information that may lead to the detection of an offence. Activists had thwarted a similar provision in the previous Bill, asserting that an act of torture must be punishable, irrespective of the reasons behind it. Do you think this provision might need a relook?

Dr. Kumar: In reply to this question, I am clearly of the opinion that the purpose and definition of torture proposed in the 2010 Bill ought to be retained and the relevant provision in the LCI Bill along with some of its other provisions need a relook. The fundamental point is to have a purposive and comprehensive anti-torture legislation which will be effective in addressing the issue of custodial torture. I do hope that the Bill will be revised in the context of its objectives and to deal effectively with all aspects of custodial torture including prosecution of delinquent public servants, including police authorities, mode and manner of lodging of complaints against custodial violence and torture, ensuring fair and impartial investigation, interim compensation, rehabilitation of victims and witnesses, speedy trial, protection of victims, grievance redressal mechanisms, education and sensitisation of police. We have waited far too long for such a law and it is only reasonable to expect that a country whose philosophical and civilization ethos is anchored in an unswerving commitment to human dignity will not be denied a fair and just legislation to secure its people against custodial torture.