Rebuilding Kerala Post-Floods : Law & Policy Perspective

Alphonsa Jojan, Jasun Chelat, Neha Kurian and Shyama Kuriakose

28 Dec 2018 1:46 PM IST

Introduction

The floods which ravaged Kerala in July-August this year was its worst natural disaster of the century. The deluge claimed 483 human lives, lives of innumerable other living beings and caused damage of over Rs. 20,000 crore.

The state witnessed the worst drought of the century in 2017 which led to severe water crisis, and a furious cyclone Ockhi in 2017 which adversely affected he coastal stretch of the state and the fishing communities, in particular. This is not to speak of the intermittent landslides and sea fury which recur in monsoons every year.

These natural disasters highlight the need to have a robust and comprehensive law and policy on disaster management and environment protection. The unique geo-physical characteristic of the state is the natural infrastructure that enables protection from natural disasters, especially in the face of the very real impacts of climate change. Kerala’s DisasterManagement Policyframed in 2010, unfortunately fails to make any reference to the role of ecosystems in providing ecological services like disaster prevention and risk mitigation, even though the Kerala State Disaster Management Plan of 2016 does talk about specific ecosystems in the event of a natural disaster. As the Post Disaster Needs Assessment (PDNA) Report of the 2018 Kerala floods acknowledges, large scale environmental degradation increased the devastating impacts of the floods.Further, the UN’s Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, 2015-2030 recommends the protection and conservation of ecosystem functions as one of the foremost ways to build resilience for preventing and mitigating disasters. This shows that environmental conservation plays a large part in disaster management and it is high time that the legislators, the bureaucracy and the citizens of Kerala consider this aspect in order to build and increase resilience in the face of impending natural disasters.

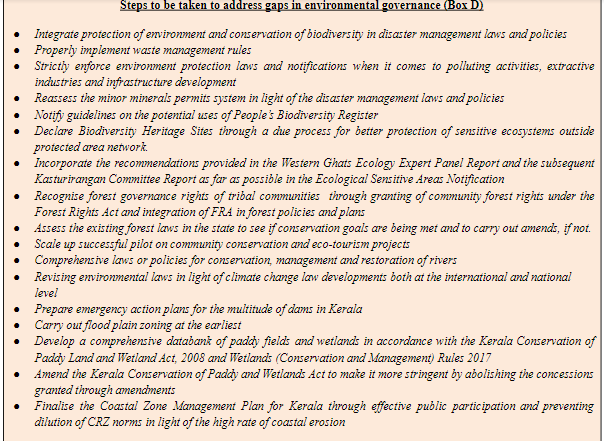

In the first part of this article, we map some key laws and policies related to environmental protection, substantive provisions of which, need to be critically reviewed, modified and integrated with disaster management and mitigation laws and policies while rebuilding a resilient Kerala to face future natural disasters. In the second part, we attempt to map the existing institutions and requirements for public participation in policy and law making and avenues for funding since it is these systemic aspects which enable ground-level implementation of laws and policies.

2. Recalibrating existing law and policy regime surrounding conservation in Kerala

While engaging in a ‘build back better’ Kerala, there is a need to look at the existing legal and policy framework on environment protection and analyse their status and understand whether it is adequate to meet the challenges mentioned above. Kerala, with its distinct geographical and ecological features, is governed by various inter-sectoral legislations and policies concerned with protection of environment and ecosystems. We are looking at them from four aspects: main laws on general environment protection covering whole of Kerala; those aimed at protection of the Western Ghats, highlands and forest diversity; those relating to rivers and their ecosystems; and finally those governing conservation of wetlands and coastal and marine diversity.

2.1. General environmental protection

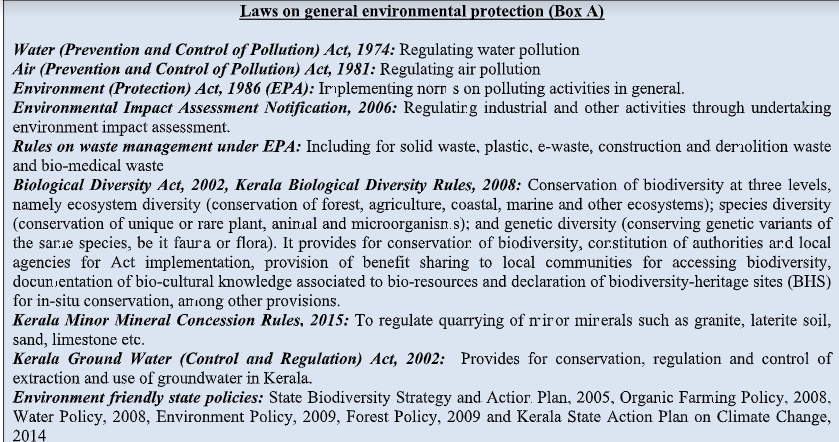

Despite the presence of so many important central and state legislations and policies given in box A, there is a lot more that needs to be done to meet the challenges at hand. Further, these laws also suffer from huge gaps in their implementation.

Take the instance of water pollution which is rampant in Kerala. Although Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act is one of the oldest environmental laws of the country, it is not adequately regulating water pollution. Natural buffer zones of many water bodies are facing major challenges and threats due to pollution from errant industries, and poor citing guidelines enforcement by Kerala State Pollution Control Board (KSPCB). Similarly, potable water sources especially groundwater is being depleted as well as polluted at a rapid rate. Adding to the woes, is the ineffective implementation of waste management rules leading to dumping of plastic and other non- biodegradable waste in water bodies. .

Besides pollution, another main issue in Kerala is unsustainable extraction of minor minerals such as granite, sand, etc. Arguably, the lack of stringent regulation under the Kerala Minor Mineral Concession Rules, 2015, non-adherence of Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Notification, 2006 and laxity in enforcing citing guidelines under the pollution control laws are reasons behind the unsustainable exploitation. Concerned by the impact of mining on ecologically fragile regions, the Supreme Court in Deepak Kumar v. State of Haryana & others, in 2012, held that all mines irrespective of their area need to be considered for environmental clearance; this was later reiterated by the Kerala High Court in various decisions in Kerala’s context. However, the number of mines- both legal and illegal in Kerala has continued to rise exponentially in recent years, in spite of the judiciary’s interventions, primarily due to the Kerala government’s mineral concession systems. Stress on ecologically fragile land especially on hill slopes has increased further as a result, and was identified as a major reason for landslides during the flood. Thus the present system of granting mining permits really needs a reassessment in line with the Kerala State Disaster Management Plan, 2016.

More recent legislations like the Biological Diversity Act, 2002 (BDA) covers a very wide ambit and is very important for a state like Kerala rich with endemic species of flora and fauna which are threatened by many activities including natural disasters. And yet, its implementation leaves a lot to be desired. In the post flood scenario, data enumeration and assessment with respect to bio-resources through mechanisms such as the People’s Biodiversity Registers (PBR) would have been very useful so as to understand the priority areas wherein conservation is required. Information gathered in People’s Biodiversity Registers prepared by BMCs can also help with the post natural disaster assessment process, since baseline data on available biodiversity is already available from the PBR. However there is no clarity as to how these registers shall be protected or utilized for these purposes. Further, though Biodiversity Heritage Sites (BHS) offer a strong legal protection to locally important ecosystems from encroachment and land conversion, no BHS have yet been declared in the state despite deliberations and consultations from 2010.

While the Kerala State Action Plan on Climate Change (KSAPCC), 2014 has identified a few sectors in the state which require specific actions with respect to climate change, there are a few gaps identified as well through a study titled ‘Climate Resilient Kerala’ done jointly by Thanal, Climate Action Network South Asia (CANSA), UNICEF and Phia Foundation. According to this study, the gaps include revising all existing laws on environmental governance in line with the latest climate change developments both at the international and national level. Most importantly, these laws need to be updated keeping in mind ecological conservation and community resilience.

2.2. Laws and policies protecting Western Ghats, highlands and forest diversity

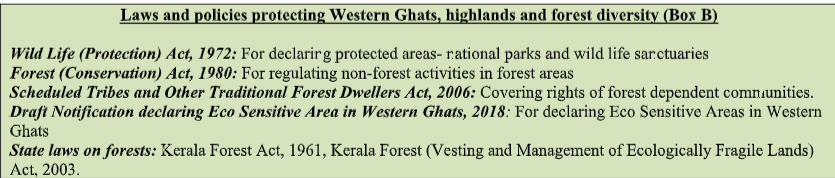

The forest and hills of Kerala including those forming part of the Western Ghats are primarily governed by a mix of central and state legislations. One of the most significant initiatives to conserve the Western Ghats region came about in 2011 as a result of the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel Report or the Gadgil Report; this was followed by the Kasturirangan Committee Report in 2012. The Gadgil Report recommended declaration of the entire Western Ghats as an Eco Sensitive Area (ESA) and provided differing degrees of restrictions on land use on the basis of varying ecological sensitivity of the specific area. The Kasturirangan Committee report was brought later which suggested less stringent restrictions on activities and reduction of areas falling within the Western Ghats ESA.

Taking cue from the recommendations of the Kasturirangan Committee Report, the Ministry of Forests and Environment (MoEFCC) directed the state governments to declare their ESAs through a draft notification on ESAs in the Western Ghats under the Environment Protection Act. The fourth draft notification on ESA for Western Ghats issued by the MoEFCC on 3rd October 2018, states that the boundary and village level details for Kerala, are available on the website of the Kerala State Biodiversity Board (KSBB). In light of impending natural disasters and the recent floods, the National Green Tribunal has stepped in and directed that the extent of areas recommended as ESAs under Kasturirangan Report should not be reduced any further. Kerala ought to now reconsider the recommendations of both the Gadgil Report and the Kasturirangan Report, and take stringent measures to prevent encroachment and regulate environmentally destructive activities including mining and infrastructure development in ecologically fragile areas. Along with reconsideration of the ESAs in the Western Ghats, Kerala should also consider the extent and implementation of the forest and wildlife laws, especially through the declaration of protected areas. The PDNA Report specifically confirmed that the environmental damage within protected areas declared under the Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972 (WLPA) in the state has been the least in comparison to other areas.

The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers Act, 2006 also known as Forest Rights Act (FRA) becomes especially important as it respects the rights of forest dwelling tribal communities who not just depend on the resources derived from these forests but also hold traditional ecological knowledge about the land they inhabit. In the event of a natural disaster, the ancient wisdom of these communities to cope with the situation needs to be recognised and translated into actionable plans. Thus, it is important that their rights over forest resources are recognized, in order to bring about conservation in a more holistic fashion. There are legislations in Kerala regulating forests, forest produce, tree felling and rights for forest dwellers but one thing in common amongst all of them is that the state has control over natural resources. Be it the case of the Forest Conservation Act, 1980, the Kerala Forest Act, 1961 or the Kerala Forest (Vesting and Management of Ecologically Fragile Lands) Act, 2003 and several other legislations on forest resources, it is not clear from any empirical evidence whether the conservation goals have been met through state control or not.

2.3. Laws related to protection of rivers and their ecosystems

Kerala has 44 rivers which play a crucial role in providing drinking water, irrigation, electricity and other ecological services such as prevention of flooding. Many of our rivers are dammed, polluted and degraded, yet there is no comprehensive law or policy towards their conservation or overall management. Some of the few law and policy initiatives such as Pampa River Basin Authority Act and the Centrally Sanctioned Scheme of National River Conservation Plan supporting ‘Pampa Action Plan’ are specific to conservation of Pampa River and are poorly implemented. Yet another legislation, titled the Kerala Protection of River Banks and Regulation of Removal of Sand Act, 2001 is meant to only regulate dredging of river sand from river banks and river beds. It is clear that there is a real dearth of laws governing river conservation. Even though the National Altlas on Wetland Inventory for State of Kerala has identified rivers and streams as major type of wetlands, Wetland (Conservation and Management) Rules 2017 has explicitly excluded river channels from the definition of wetlands.

There is also no concrete law or policy on flood plain mapping. The only framework which comes close is the requirement for Emergency Action Plans under the Dam Rehabilitation and Improvement Project, a scheme implemented by the Central Water Commission (CWC), for the dams built on these rivers. Focused on emergency situations, the guidelines instruct the identification of likely catastrophic floods in the event of failure of the dam, along with the probable areas, inundation maps, population, structures and installations likely to be adversely affected due to flood water release. However the Comptroller and Auditor General audit in 2017 showed that in the case of Kerala, none of the dams had emergency action plans in place. In addition, as with the Disaster Management Policy, even the Emergency Action Plan primarily focuses on dealing with the situation post occurrence rather than ensuring better upkeep of the river basin in its entirety. The CWC as early as 1975 had proposed a legislation for flood plain zoning including maintaining restrictions on land use, however the same never came into being. As of now the only restrictions on infrastructure development are the local Building Rules which is more of a permissive legislation, irrespective of where the relevant development is being done. The recently proposed draft River Basin Management Bill, 2018 aims at evolving integrated water resource management principles for inter-state river basins. This may have implications for Kerala also.

2.4. Laws governing conservation of protection of wetlands, coastal and marine diversity

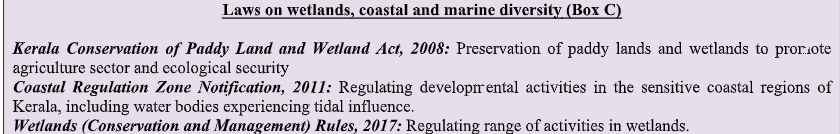

Besides, the 44 rivers, Kerala is also endowed with a coastal stretch of 580 kms and numerous coastal wetlands including lagoons, mangroves, sandy beaches. The coastal stretch is primarily regulated by the Wetland (Conservation and Management Rules), 2017, Kerala Conservation of Paddy Land and Wetland Act, 2008 and the Coastal Zone Regulation Notification, 2011 (CRZ Notification).

The Kerala Conservation of Paddy Land and Wetland Act, 2008 has been heavily debated in the aftermath of the floods. In addition to the shoddy enforcement of the Act, it suffers dilutions due to various amendments. A recent amendment in 2018 has allowed the government to grant exemption from the requirements under the legislation if the conversion of paddy fields and wetlands is for public purpose. An earlier amendment in 2015 permitted regularization by the district administration of unauthorized reclamation, prior to 12th August 2008 by payment of a nominal fee of Rs. 500 supported by certain documentary evidence. The need of the hour is to make the legislation more stringent instead of retaining the diluted provisions of the legislation. Further, in spite of so much time having passed after its enactment, the state still does not have a comprehensive databank of paddy fields and wetlands. In addition to this state law, there are also the Wetlands (Conservation and Management) Rules, 2017 introduced by the central government according to which every state is supposed to come out with an identified list of wetlands. This exercise is also yet to be completed.

With the long coastline of Kerala, the CRZ Notification, 2011 gains significance. However, it is unfortunate that even today the Coastal Zone Management Plans (CZMP) which determine the classification of coastal stretches, are yet to be published after taking into consideration the local communities’ concerns. Even worse is Kerala’s suggestion to the CRZ Notification reviewing committee headed by Shailesh Nayak to reduce the extent of no-development zone in rural areas (CRZ-III) and to provide special concessions for tourism. These recommendations need to be retracted and reframed so as to ensure that no constructions are encouraged in vulnerable areas for any purposes including housing and tourism.

While effective implementation of many of these enactments have been affected by systemic issues with the regulatory authorities themselves, a serious review of these enactments in light of the floods and potential climate disasters is necessary if we are to rebuild a Kerala which is more resilient.

3. Increasing public participation and decentralised governance in Rebuilding Kerala

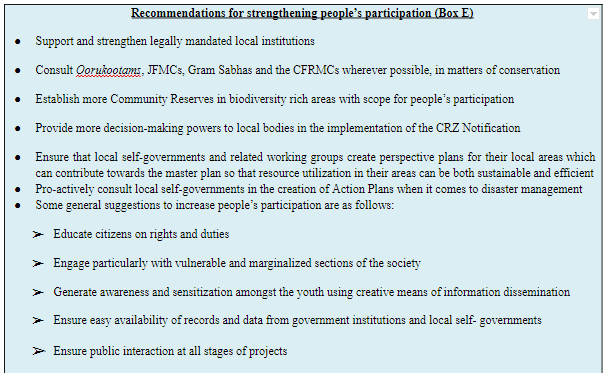

3.1. Role of legally mandated local level agencies

Kerala has always led the way in addressing many concerns of inequality, illiteracy, etc., through active decentralised institutions. Strengthened by the 73rd and the 74th amendment to the Constitution recognising the third tier to governance, i.e., local self governments (LSGs), the state’s Panchayati Raj system is hailed as one amongst the most successful and effective models in India. The local self-government bodies are efficiently planning and implementing various developmental and welfare schemes and regulating various key environmental activities including waste management.

We need to sustainably and continuously support and build capacities of LSGs and other legally mandated local bodies while undertaking rebuilding activities. Besides, the LSGs, statutory bodies such as Biodiversity Management Committee (BMC) constituted by the LSGs under the BDA should be encouraged. Kerala government has already designated BMCs as Environmental Watch Groups at the gram panchayat level to deal with environmental issues at the panchayat level. The government should provide enough capacity to BMCs to discharge their responsibilities concerning environmental protection.

Similarly, in forest areas, Oorukootams or hamlet level committees, Joint Forest Management Committees, Gram Sabhas (wherever formed) and the Community Forest Resource Management Committees (CFRMC) constituted under FRA should be consulted and empowered to undertake similar activities. The indigenous and traditional ecological knowledge become especially relevant while implementing the management plan prepared by CFRMCs, for rebuilding forest ecosystems. Further, there are traditional community managed areas near protected areas such as Wildlife Sanctuaries and National Parks, which may be declared as “Community Reserve” under the WLPA to be managed and protected by local communities. In Kerala, currently, there is only one such Community Reserve, the Kadalundi-Vallikunnu Community Reserve while there is certainly scope to declare more such areas, given the state’s rich biodiversity. At present, there are initiatives by the forest department in social forestry projects and joint forest management initiatives which have encouraged participation by tribal communities and forest-dependent villagers in forest conservation. Also, the work done by officials and communities in the Periyar and the Parambikulam Tiger Reserves have resulted in increased livelihood opportunities for the tribal communities in eco-tourism projects along with fostering well-being of the protected area and its animals. It would do well for such projects to be scaled up in other parts of the state too. Further, in highlands, communities and also plantation groups should be encouraged to take up conservation activities, either under the ESA or the local self-governance frameworks.

Despite the 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendment Act of 1993, there are still plenty of laws which do not take into consideration, the importance of decentralised governance. Take the case of the CRZ Notification. The local bodies are only mandated to implement the demarcation of the cadastral maps based on the coastal zone management plans prepared by the central and state agencies. The lowest body is at the district level committee which does not have any role in planning, but is only expected to assist state level bodies in enforcement and monitoring of the Notification. This is not an ideal state of affairs, especially since they are the ones who are closest to the ground level actualities and the people.

Unlike the CRZ Notification, the KSAPCC mentions the importance of local self-governments in addressing challenges due to climate change. Pursuant to this policy, the state government has initiated projects like carbon neutral panchayats for preparing residents, panchayat members towards mitigation and adaptation to climate change. The local self-governments and related working groups should reinvigorate their role in mitigation and adaptation measures within their local area through data collection and creation of perspective plans. These plans can help contribute towards the master plan so that resource utilization in their areas can be both sustainable and efficient.

Another area in which local level agencies need to be empowered is disaster management itself. Despite the organic coming together of the local community, local self-government bodies and the state government during these floods, the disaster management law has a flawed design as far as the response system at the local level is concerned. It can also be observed that the legal framework of relief, rescue and rehabilitation mechanism in India is in most areas, centred on government authorities at the district level, particularly District Collectors, on whom local self-government agencies are dependent on, for information, personnel and coordination. This framework provided by the Disaster Management Act, 2005, has been criticised for the lack of attention it gives to local bodies like Panchayats. The Act lays down details of “Action Plans” to be followed at the national level, state level and the district level but does not recognise local self- government bodies (although it mentions that the plan should be made in consultation with local authorities, but without providing any further details/prescribing any specific requirements). In fact, Kerala, in keeping with the structure of the Act, the State Disaster Management Authority and the District Disaster Management Authority are already in place, but no such authority existed at the level of local government. Kerala’s Disaster Management Policy, 2010, mentions “local bodies” as important stakeholders in disaster management. However, again, their role seems to be to function purely within the ambit of the framework “mandated by and in coordination with” the state and district level government departments and agencies.

3.2. Importance of people’s participation

Similar to the role of LSGs and other legally mandated bodies, people’s participation is a crucial aspect in environmental governance and disaster management. One of the often quoted “good things” which came from Kerala’s response to the floods was the active participation of the local people themselves in relief and rescue operations. The fishing community with their specialised knowledge and skills provided crucial assistance to the state machinery in the rescue operations.

In the past also, people and local communities have taken centre-stage in environmental movements, just as they continue to do so, in Kerala. “Save the Silent Valley” movement in the 1970s, various “Save the River” campaigns, the Coca-Cola Virudha Samara Samiti’s movement against groundwater exploitation by the Coca Cola company in Plachimada are some such notable movements in Kerala. The campaign against the solid waste treatment at Vilappilshala underpins the struggle carried out by Panchayats and other local self-governing bodies to protect their homes and lives.

While most of these collectives have been formed in response to specific issues, Kerala also has many collectives working for conservation of environment and related human rights. One such collective is the Kerala Sasthra Sahitya Parishad (KSSP) which has been leading the people’s science movement and effectively influencing and framing public discourse on implementing alternative models for development, with emphasis on equity and sustainability. Also, the Kerala Adivasi Gothra Mahasabha, Kerala Swatantra Matsya Thozhilali Federation and numerous NGOs attached to the cause of environment and people have also served as a strong rallying support behind marginalised voices.

Thus, it is important that such participation is encouraged with meaningful inclusion in decision making. This can be ensured through respecting fundamental rights of citizens for free speech and association, mandating public consultation before environmental decision making, facilitating filing of Right To Information (RTI) applications and educating citizens’ on rights and duties along with sensitization so as to allow them to make informed decisions on a day to day basis. Often, the vulnerable and marginalized sections of society get ignored in the decision making process. Such sections should be engaged by using different methods including affirmative action. In addition, children and young students, the future generations, should also be sensitised and made aware. Public spirited movements often get thwarted due to the lack of easy access to public information and even though the right to information exists, not everybody uses it, due to low levels of awareness. Government institutions including local self- governments should ensure easy availability of records and data relevant for decision making by the people. Further, public interaction should be encouraged at all stages of law, policy and plan designing and enforcement.

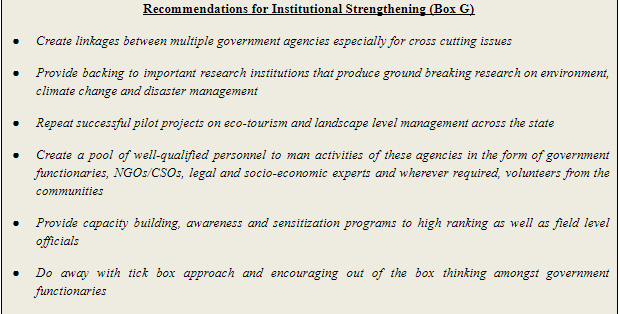

4. Institutional Strengthening

Government institutions in the state of Kerala, responsible for environmental governance have been quite pro-active since their inception. In fact, these state agencies have been a step ahead with respect to implementation of various forest, environmental and biodiversity related projects, as opposed to several other states.

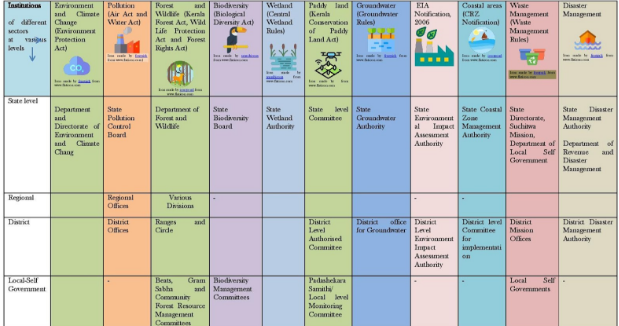

The institutional framework for protection of environment and conservation of forest and biodiversity mainly consists of government departments, government directorates, statutory institutions and government aided /autonomous research institutions. In Kerala, an independent department of environment was formed in 2006 by delinking it from the existing Science, Technology and Environment. The current avatar of the department includes within its ambit matters relating to environment and climate change, hence the department was renamed in 2010 as department of environment and climate change. The secretariat co-ordinating the activities is the Directorate of Environment and Climate Change. The department of forest and wildlife, agriculture, fisheries and water resources form crucial inter-linkage for environmental governance. Various institutions are also constituted under various legislations for the purpose of conservation. Table 1 provides an overview. This is to demonstrate the need for synergy between institutions especially for cross cutting issues, rather than the outmoded method of working in silos. There are also policy suggestions for constitution of specialised bodies such as a State Level River Authority along with organisations for river basin and river sub-basin under the Kerala Water Policy of 2008.

Table 1

Table 1Apart from the government agencies, there are several state-supported research institutions as well, which conduct a good amount of research and analysis on the above-mentioned issues. Some of the notable institutions mentioned below should be provided as much backing as possible, in their endeavours.

In addition, there are several eco-tourism/ landscape based programs based around protected areas developed by the State Forest Department. Periyar and Parambikulam Tiger Reserves have become successful models for such programs in the state. Further, initiatives have been taken by the KSBB to implement the Act in its entirety in the state. It has carried out impressive programs to document the biodiversity especially to identify flood and drought resilient varieties of plants and breeds of animals, albeit in an ad hoc manner. In light of the 2018 floods, the KSBB is undertaking a survey on the impact of floods on biodiversity of the state, importantly riverine biodiversity, fish migration, riparian vegetation, invasive species, agricultural crops, mangroves, soil biota etc. This is a laudable effort. The Green Protocol has been introduced in the state by the Suchitwa Mission which is a technical support group under the local self- government department prohibiting the use of one-time use plastics in public events and parties. The Suchitwa Mission has also been making great strides in waste management.

However, the success stories are few and far between. Generally, it can be seen that environmental agencies have been bogged down by bureaucratic hurdles, red-tape, corruption and lack of capacity building, amongst other issues. It has been observed that the Kerala KSPCB and its regional offices have not fared as expected in implementation of environmental norms and control of pollution. The reasons for these problems need to be properly identified so as to take prompt remedial action. Take for example, the State Environment Impact Assessment Authority which considers Category B projects under the ambit of the EIA Notification has still not been constituted since the term of the previous authority got over in February this year. When it comes to the role of the forest department, it needs to be added that while forest conservation programs are being undertaken proactively, the department should put in all its energies towards community participation and carrying out afforestation activities with the help of endemic varieties of plants and trees.

Capacity building, awareness and sensitization programs must be properly implemented for the benefit of field level as well as senior officials so that their efficiency can be cutting edge. This helps with removing concerns and misconceptions amongst the officials, getting information on emerging environmental governance concepts and also allows them to pass along communication in a responsible manner to the communities. Further, it is important that agencies do away with tick box approach and encourage out of the box thinking through live engagement with professional experts, community members and civil society organisations when it comes to conservation efforts. As mentioned above, Kerala is a state with a complex set of socio-ecological challenges and resolving the same while rebuilding a better Kerala, would require some innovative solutions. These solutions may not always be found within the law or manuals of government functionaries and might necessitate brainstorming with experts, and reverting to traditional wisdom of communities.

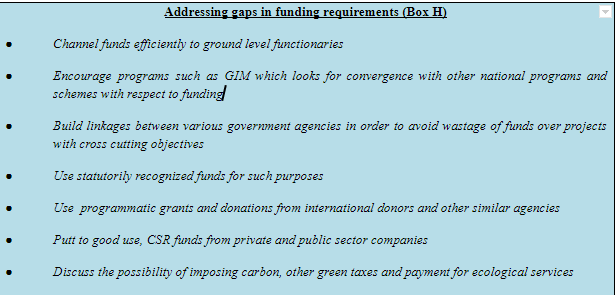

5. Managing Funding Requirements

Another challenge faced by government agencies is the aspect of funding for implementation of environmental programs. It is quite a common sight to see a project lapse due to dearth of funds. Usually such fund shortage could be attributed to state or central budget allocation. At other times, funds are available; however the same is not being channelled efficiently to communities. There are different means to resolve these issues but this again requires creativity. Lessons from other states could be adapted here. Thus for example, the program under Green India Mission (GIM) looks for convergence with other national programs and schemes including Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, Compensatory Afforestation Fund Management and Planning Authority, National Afforestation Program, National Rural Livelihood Mission, Integrated Watershed Management Program, Programs of Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, National Rainfed Area Authority etc. in and around forest and non-forest areas and mini and micro water-sheds. This would tie up efforts under various departments with fund generation from under each of these heads. The recent approval received for state of Kerala from National Executive Council under GIM for its Annual Plan of Operation and Perspective Plan is especially well-timed. Agencies also need to figure out how to integrate, scale up and replicate successful pilot projects across the state so as to allow projects to sustain themselves beyond the project period to ensure sustained interest.

It is usually observed that different institutions with cross cutting objectives conduct different programs in the same area, often leading to wastage of tax payers’ money. Developing links between these agencies are crucial to avoid such waste. Statutorily recognized funds such as the Local Biodiversity Fund under the BDA, River Management Fund under the Kerala Protection of River Band and Removal of Sand Act, 2001 and the State Environment Fund under the State Environmental Policy, among others need to be used efficiently for such purposes. CSR funds from private and public sector companies can also contribute.

Further, for conservation of globally important sites such as the Western Ghats, Vembanad-Kole wetlands, Ashtamudi, there is much potential for gathering international funding. Tags under RAMSAR for wetlands as well as UNESCO World Heritage Sites entitle these areas to funding in the form of programmatic grants. Funds received for these purposes should be utilized properly to make such areas and people dependent on these sites environmentally resilient. As the draft PDNA report suggests, grants and donations from bilateral agencies and international agencies working on environment and development must be encouraged. In addition, the possibility of imposing carbon, other green taxes and payment for ecological services, must be discussed as a means of mobilising revenues for the state.

6. Conclusion

Admittedly, the floods of 2018 have been an eye opener in several respects. On the positive, it brought together the people and state machineries. The state has led the way with efficient rescue and relief efforts both during and after the floods. Reduced number of casualties for a state so densely populated, is proof of this. Yet, as mentioned above, it is important to be prepared in the wake of such disasters. These floods have also thrown light on the ecological fragility of the state, weak status of implementation of environmental laws, need for better engagement with local communities and institutional strengthening. It is hoped that these lessons will be incorporated into both short term and long term programmes being undertaken by the state of Kerala and together we will move into a resilient future.

(About the authors : Alphonsa Jojan & Jasun Chelat teach law at Tamil Nadu National Law University; Neha Kurian is an advocate and researcher of environmental governance & climate change; Shyama Kuriakose is an independent legal consultant writing on environmental issues)

(The article does not reflect the views of Live Law. The article contains the personal views of the authors)