Scope of Section 11 (6) of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

Divyanshu Bhandari & Aaditya Vijaykumar

19 Jun 2021 5:13 PM IST

Under the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, the two guiding principles in appointment of arbitrator(s) are party autonomy and minimal court interference. Nonetheless, there are instances like Oyo Hotels and Homes Pvt. Ltd. vs. Rajan Tewari & Anr. where courts have initiated arbitral proceedings by intervention.

S. 11(6) of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act lays down a mechanism for judicial appointment of an arbitrator. It contemplates 3 scenarios wherein courts may appoint an arbitrator. These include:-

- When both parties fail to act as per the procedure prescribed;

- When parties or appointed arbitrators fail to reach an agreement with respect to appointing a third arbitrator under that procedure; or

- When a person, institution fails to perform any function entrusted to him or it under the procedure.

On a literal construction of S. 11(6), courts are empowered to save the arbitral proceedings from failing by judicially appointing an arbitrator. In Datar Switchgears Ltd. vs. TATA Finance Ltd. and Anr. this power was further extended to include those scenarios wherein the arbitral clause did not contain an appointment procedure.

S. 11(6) has been the focal point of several judgments and has undergone extensive amendments. To truly appreciate the implications of S. 11(6), one needs to understand its judicial and legislative history.

Appointment of Arbitrator by Court: Judicial or Administrative?

The first controversy surrounding Section 11(6) was whether an appointment order is considered judicial in nature and thus amenable to Article 136 or purely administrative and hence beyond Article 136. The position has evolved over time.

In Sundaram Finance Ltd. vs. NEPC India, while considering the scope of Section 9, it was observed that an appointing order is not considered judicial. Moreover, this observation was fleshed out in Ador Samia Private Limited vs. Peekay Holding Ltd. wherein once again an appointment order was held to be purely administrative in nature. The same position was upheld in Konkan Railways Corporation Ltd. vs. M/S Mehul Construction and reiterated in Konkan Railways Corporation Ltd. vs. Rani Constructions Pvt. Ltd.

In State of Orissa vs. Gokulanada Jena the Supreme Court again refused an Article 226 challenge to an appointment order, holding that an alternative remedy was contemplated under Section 13.

Ultimately, this controversy was laid to rest in S.B.P. & Co. vs. Patel Engineering Ltd. and Anr. wherein Rani Constructions (supra) was set aside with prospective effect and it was concluded that a Chief Justice under S. 11(6) exercises judicial, not administrative powers, so an appeal under Article 136 would be maintainable.

Unfortunately, this judgment laid the seeds for the next controversy. In Paragraph 46 (iv) of S.B.P. & Co. vs. Patel Engineering Ltd. and Anr. (supra), courts were permitted to travel beyond merely determining the validity of an arbitral clause and look into the existence of a live claim.

Mini-trial at the Stage of Judicial Appointment:

The wide interpretation of Section 11(6) given in S.B.P vs. Patel Engineering (supra) gave rise to mini trails at the appointment stage as parties could now argue upon the merits of a claim to convince the court of the existence or otherwise of a live claim.

Consequently, in National Insurance Co. Ltd vs. M/S. Boghara Polyfab Pvt. Ltd. S. 11(6) was diluted and 3 categories warranting judicial interference were established:

- Issues which the Chief Justice or his Designate is bound to decide;

- Whether the party making the application has approached the appropriate High Court.

- Whether there is an arbitration agreement and whether the party who has applied under Section 11, is a party to such an agreement.

- Issues which he may choose to decide; and

- Whether the claim is a dead (long barred) claim or a live claim.

- Whether the parties have concluded the contract/ transaction by recording satisfaction of their mutual rights and obligation or by receiving the final payment without objection.

- Issues to be left to the Arbitral Tribunal to decide.

- Whether a claim made falls within the arbitration clause

- Merits or any claim involved in the arbitration.

More judicial attempts were made to temper Section 11 (6) in Shree Ram Mills Ltd. vs. Utility Premises and Indowind Energy Ltd. vs. Wescate (India) Ltd. and Anr.

The 246th Law Commission Report, recommended 4 amendments to dilute the power of judicial appointments under 11:

- Diluting the appointing power of a Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and High Court thus permitting other benches to appoint arbitrators. (never implemented),

- Inserting S. 11 (6A) (thereby limiting judicial scrutiny to only determining the validity of an arbitral clause),

- Inserting S. 11 (7) (whereby decisions concerning appointment were final and non appealable),

- Inserting S. 11 (13) (whereby courts would endeavour to appoint an arbitrator within 60 (Sixty) days).

Consequently, vide the 2015 Amending Act three of the aforementioned recommendations i.e., insertion of S.11(6A), (7) and (13) were implemented. These amendments laid the foundation for several landmark rulings like Duro Felguera S.A. vs. Gangavaram Port Ltd. and NCC Ltd. vs. Indian Oil Corporation Ltd.

Unfortunately, despite these measures, in United India Insurance v Hyundai Engineering yet another attempt was made to enlarge S. 11(6A). The Court once again travelled beyond S. 11(6A) and decided the dispute on merits. To add to the confusion, the 2019 Amendment Act omitted the newly inserted S. 11 (6A) and S. 11 (7).

Consequently, as on date, courts by virtue of S.B.P. and Co (supra) and Polyfab (supra) have significant powers with respect to the appointment procedure. Nonetheless, courts continue to exercise due caution and follow S. 11(6A) in principle. Judicial interference is (usually) limited except in cases where:

- Either party contends fraud, coercion or duress in the arbitral agreement. (Union of India and Ors. vs. Master Construction Company);

- The arbitration agreement stands novated. (Damodar Valley Corporation vs. K.K. Kar);

- Issues involve territorial jurisdiction (GE Countrywide Consumer Financial Services Limited vs. Surjit Singh Bhatia and Ors.);

- There is non compliance of the procedure mentioned in the arbitral clause (Larsen & Toubro Limited vs. National Highways Authority of India and Ors. 276 (2021) DLT 422);

- It impacts the capacity/capability of arbitrators, etc.

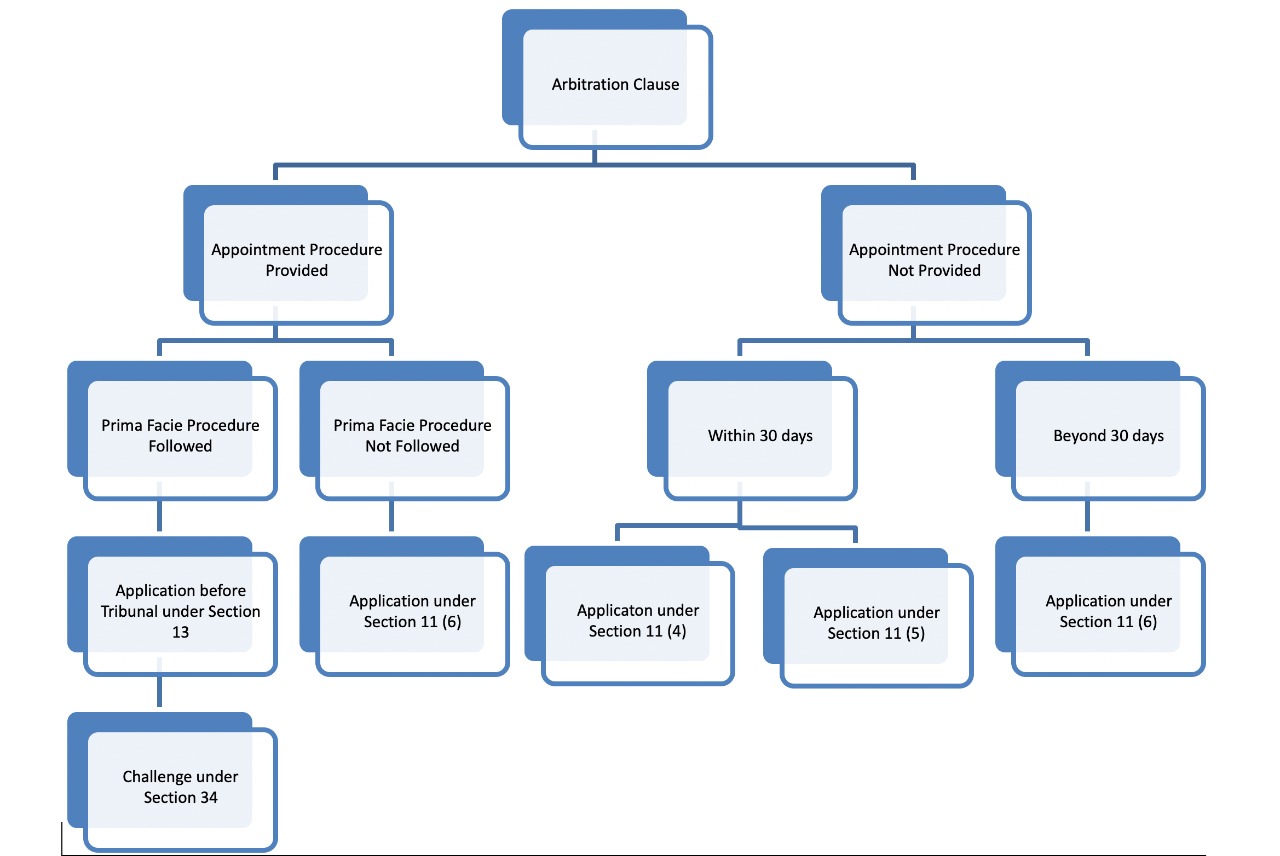

Current Mechanism for Appointment of Arbitrator:

Accordingly, the current mechanism seeking court appointment of an arbitrator is reproduced hereunder: -

S. 11(2) grants significant autonomy to the parties in selecting the procedure for appointing an arbitrator. Where such a process is defined in the arbitral clause, either party may issue a formal request seeking appointment of arbitrator(s). If the other party agrees, the matter is relegated to arbitration.

However, if the other party disagrees or does not respond, the first party may then file an application before the court seeking appointment of arbitrator(s). This application can be made under S. 11(4) or (5) within 30 days, or under S. 11(6) if the request is made after 30 days.

Per Contra, in case of a dispute regarding the appointment, the court may:

i) Appoint an arbitrator and direct them to decide their own competence (in case arbitration proceedings have not commenced); or

ii) Appoint a new arbitrator in case the erstwhile arbitrator was appointed without following the stipulated procedure or the appointment suffers from a patent illegality (in case arbitration proceedings have commenced); or

iii) Dismiss the appointment application.

In case of dismissal, under S. 13 the disputing party has the right to re-agitate competency before the arbitrator. If the arbitrator dismisses this application then competency becomes a ground for challenge under S. 34 (2).

The decision given is S.B.P. and Co. (supra) appears to have been correct in holding that a S. 11(6) order is judicial in nature. Nonetheless, the judgment travelled beyond its scope and violated the Kompetenz-Kompetenz principle. Consequently, the line between S. 16 and judicial intervention currently stands blurred, despite several positive judicial and legislative activism.

The 2019 Amendment Act has brought the matter right back to square one. Polyfab (supra) remains the balancing bridge between judicial interference and the Kompetenz-Kompetenz principle.

Views are personal.

Authors are Advocates Practising at New Delhi