Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co : A Landmark Decision Which Came Amid An Epidemic

Nadeem Kottalath

30 March 2020 11:41 AM IST

Next Story

30 March 2020 11:41 AM IST

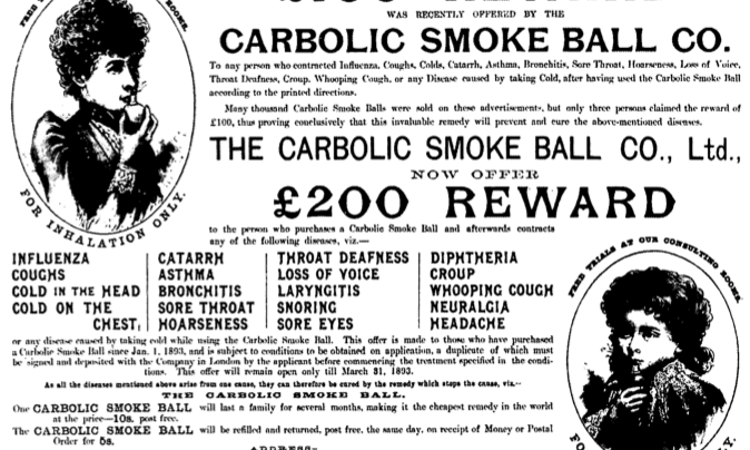

Placebos and fake medicines promising cures emerge whenever society is faced with epidemics. There will be elements in society, who will try to make quick money through offers of magical cures by exploiting the gullible sections in the wake of the inability of established medicinal systems to offer ready remedies to a novel disease.One such attempt by a company during the influenza epidemic...