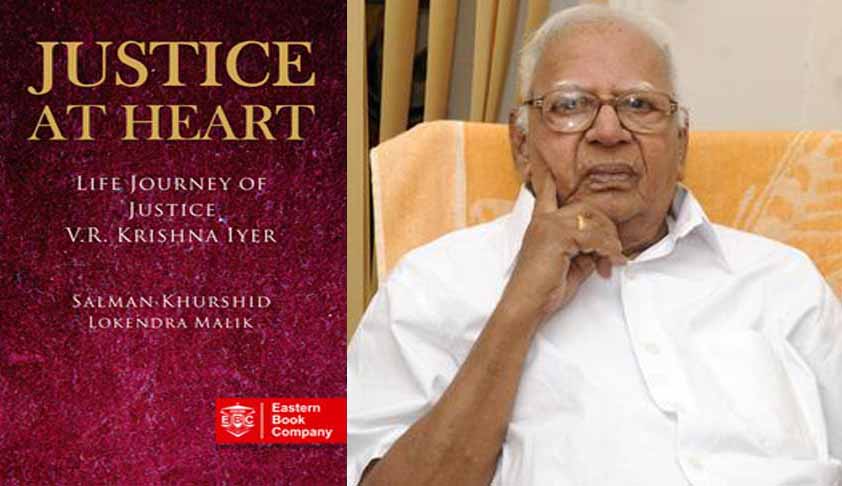

Justice Krishna Iyer: A Remarkable Blend Of Judicial And Humanistic Approach To Life And Its Problems

Review Editor

4 Dec 2016 11:28 AM IST

Next Story

4 Dec 2016 11:28 AM IST

On December 5, we will be observing the second anniversary of the passing away of Justice V.R.Krishna Iyer. The two years since his passing away have seen an extraordinary interest in the contribution of Justice Iyer to Indian Supreme Court’s jurisprudence, and to the quality of India’s public discourse, after his retirement. Although his tenure in the Supreme Court lasted only for...