Film Certification In India And The Curse Of Pre-Censorship

Arjun Natarajan

2 Jun 2017 3:00 PM IST

Prelude

I’ve come across several news reports concerning Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) and a film called An Insignificant Man.

This piece is not about An Insignificant Man or about what the CBFC has said about it.

However, the said news reports have prompted me to write on pre-censorship of films in India, which is unfortunately being passed off as film certification.

For starters, I am setting out the ascending order of interference by the government with peoples’ rights:

- Regulation

- Control

- Prohibition

I shall very briefly distinguish between regulation, control and prohibition by way of three examples:

- The role of a traffic police personnel on any given day is that of regulation. He ensures that the traffic moves smoothly and seamlessly. In order to ensure the same, he might even stop the traffic. However, he does not ask a limousine as to why it is longer than other cars.

- The role of a traffic police personnel on say, Republic Day, is that of control. He ensures that the traffic does not interfere with smooth and seamless conduct of Republic Day celebrations. In order to ensure the same, he may completely restrict traffic movement on some roads. However, it is not his duty to do so as a matter of routine.

- Say, by law, gambling is completely barred in a particular locality. That is called prohibition. The role of a police personnel in bringing to book gamblers in that locality is that of enforcing the said prohibition.

Where do I fit in certification?

In my view, certification is neither control nor prohibition. At its best, certification is regulation, and that too, a very subtle form of regulation.

At this juncture, I would like to remind you that India’s pride for Vatsyayana is as much as it is for Valmiki and Vyasa. Yes, I am referring to the Vatsyayana of Kama Sutra fame.

To this day, India is a liberal democracy where what is not legally prohibited is legally permitted.

However, in India, it is pre-censorship of films i.e., censorship even before it is viewed by the public, which is masqueraded as film certification.

Film is an art. The creators of any art are as conversant with censorship, as censorship is conversant with art. It would be foolish to hope that if the creators of art start thinking about censorship, then censorship shall also reciprocate.

Before proceeding any further, a flashback to 1970 is important. Back then, in KA Abbas versus The Union of India & Another, (1970) 2 SCC 780, it was held by the Supreme Court that censorship of films in India, including prior restraint i.e., pre-censorship, is justified under the Constitution.

Back in the day, films in cinema halls were probably the only powerful medium of mass communication.

Cut to the present day. The television broadcasting industry has grown by leaps and bounds. Today, the internet has emerged as the most powerful medium of mass communication. It has definitely overtaken the television broadcasting industry.It would not be wholly wrong to say that internet is on the verge of taking over the television broadcasting industry.

Let us face it. Today, films cease to be a powerful medium of mass communication vis-à-vis the television broadcasting industry and the internet.

It is, indeed, some sort of a video killed the radio star scenario, playing at a different pedestal altogether.

However, films continue to be the most regulated in India.

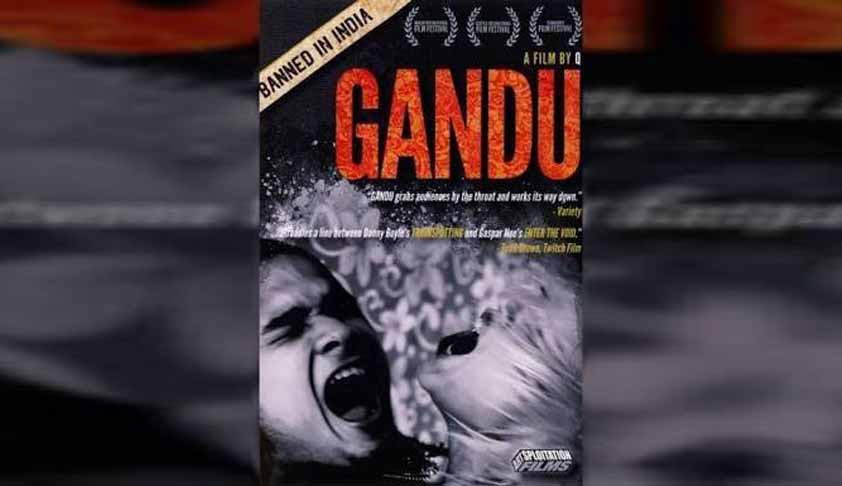

In India, it is a curse for art to manifest itself as a film. In India, films have to undergo the brutalising process of pre-censorship i.e., they are scrutinised before they are made public. However, television content and internet content, which wield more power than films as a medium of mass communication, do not have to endure pre-censorship in India.

Pre-censorship is the curse of being a film in India. If an Indian film were to be a tragic hero, its hamartia would be its own identity of being an Indian film.

Even after over two decades of the Supreme Court’s judgment in The Secretary, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting versus Cricket Association of Bengal & Another, (1995) 2 SCC 161, wherein the apex court held that under the Constitution, citizens have the right to know and to receive information, the said rights have all along been compromised on account of the statutes that govern film certification in India, namely the Cinematograph Act, 1952, and Cinematograph (Certification) Rules, 1983 (Certification Rules, 1983).

The story of a film

Before a film is released, it is very closely scrutinised by the CBFC. I am being polite while using the word “scrutinised”.

Let me borrow from what The Doors have to say about the Earth in When The Music’s Over. The film is ravaged and plundered and ripped and bitten and stuck with knives and tied with fences and dragged down. Quite literally.

With this pointless or avoidable description of violence, cruelty and horror, which may have the effect of de-sensitising or de-humanising you and offending your human sensibility by depravity, I shall endeavour to walk you through the problems embedded in the law of film certification in India, which cause it to regress and reduce it to pre-censorship of films in India.

On a different note, the underlined content is a verbatim reproduction of the Central government’s guidelines issued on 06.12.1991, under the Cinematograph Act, 1952. The said guidelines are still in force. More on the guidelines later in this piece.

The law of 1952:

The CBFC has been constituted for the purpose of sanctioning films for public exhibition.

The Cinematograph Act, 1952, mandates that the Central government appoints the chairman and members of CBFC. However, the Cinematograph Act, 1952, and Certification Rules, 1983, are so lacking that a film, which is a work of art, is to be sanctioned for public exhibition by an authority manned by a chairman and members, whose qualification/s are unspecified. Such an authority, while examining films, is empowered to think as necessary, some excisions or modifications in the film, even before it is viewed by the public. If it thinks so, it is empowered to direct the filmmaker to carry out such excisions or modifications in the film. If the CBFC is to act as the custodian of the public’s conscience, then, the least that is required is that the qualification/s of those constituting it must be prescribed.

Thankfully, a direction to carry out excisions or modifications can be given by the CBFC only after giving an opportunity to the filmmaker for representing his views in the matter.

To me, this doesn’t seem to be of much avail. I say so, because, there being no prescribed qualification/s for the persons constituting the CBFC, it is questionable as to whether the CBFC can even appreciate the views which are represented by the filmmaker, as to why he is not agreeable to carry out the excisions or modifications. It would not be out of place to mention that the CBFC attained the power to direct filmmakers to carry out excisions or modifications only in the year 1983, by way of an amendment to the Cinematograph Act, 1952. Prior to the said amendment, the CBFC was not empowered to direct filmmakers to carry out excisions or modifications.

For the purpose of enabling the CBFC to efficiently discharge its functions under the Cinematograph Act, 1952, the said statute provides that the Central government may establish advisory panels, at regional centres.

The CBFC may consult any advisory panel, in respect of any film for which an application for a certificate has been made. Such panels shall be duty bound to examine the film and to make such recommendations to the CBFC as they think fit.

It transpires that advisory panels play a significant role to enable the CBFC to efficiently discharge its functions under Cinematograph Act, 1952. However, as per the said statute, the persons constituting such panels shall be qualified in the opinion of the Central Government to judge the effect of the films on the public. Even Certification Rules, 1983, do not provide any criteria for appointment of its members. In fact, the only prescription is that the Central government may, after consultation with the CBFC, appoint any person whom it thinks fit to be a member of an advisory panel.

In other words, the qualification to be a member of an advisory panel is that, in the opinion of the Central government, the person shall be qualified to judge the effect of the films on the public.

Once again, neither the Cinematograph Act, 1952, nor does any other law say anything as to what qualification/s a person is required to have to judge the effect of the films on the public. This deficiency has also been existent all along.

This deficiency, read with the fact that the qualification/s of the chairman of CBFC and the qualification/s of the members of CBFC has been lacking, is quite a script, which can sound the death knell for film certification in India. The fact that these advisory panels examine films and make recommendations to the CBFC as they think fit, is like a colour blind person advising a blind person as to how the red colour in red roses looks like.

The principles which guide film certification, as contained in the Cinematograph Act, 1952, indicate that they reiterate the reasonable restrictions contained in Article 19(2) of the Constitution i.e., a film shall not be certified for public exhibition if, in the opinion of the CBFC, the film (wholly or partly) is against the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the state, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency or morality, or involves defamation or contempt of court or is likely to incite the commission of any offence. Subject to these provisions, the Central government may issue such directions as it may think fit, setting out the principles which shall guide the CBFC to grant certificates under the Cinematograph Act, 1952, in sanctioning films for public exhibition. The Central government’s guidelines issued on 06.12.1991, under the Cinematograph Act, 1952, are still in force.

The guidelines of 1991:

The objectives of the said guidelines, along with my comments, if any, are as under:

- The medium of film remains responsible and sensitive to the values and standards of society – Which society is under reference? What are its values? What are its standards? Expecting the medium of film to remain responsible to such unknown parameters is preposterous.

- Artistic expression and creative freedom are not unduly curbed.

- Certification is responsible to social changes.

- The medium of film provides clean and healthy entertainment – Presuming that clean and healthy are universal, what is entertainment? Insisting that the medium of film provides entertainment which is clean and healthy is ludicrous, because, entertainment is subjective. Writing this piece was entertainment for me. Reading it is a chore for you.

- As far as possible, the film is of aesthetic value and cinematically of a good standard – The maker of a film has a choice to make it with aesthetic value and cinematically of a good standard. It follows as a logical corollary that, he has a choice to make it without aesthetic value and cinematically not of a good standard too. He decides what is aesthetic value and cinematically of good standard, for himself.

The objectives being such, I do not see much of a point in delving deep into the guidelines. However, I’d like to give an example. Let us take a film which is intended to create awareness about drug addiction. It should definitely not glorify or justify drug addiction. However, the modus operandi of peddlers and addicts, other visuals or words have to be shown, as they are germane to the theme. But such showing gets hit by a guideline that in pursuance of the objectives, the CBFC shall ensure that the modus operandi of criminals, other visuals or words likely to incite the commission of any offence are not depicted. The objectives which come into play could be all or anyone of (i), (iv) or (v).

In such a film, the script might demand portrayal of a chronic drug addict’s physical and mental state when he desperately needs his drug but does not find it. However, showing such a scene is most likely to have the effect of de-sensitising or de-humanising people. It gets hit by a guideline which requires that in pursuance of the objectives, the CBFC shall ensure that such scenes as may have the effect of de-sensitising or de-humanising people are not shown. The objectives which come into play could be all or anyone of (i), (iv) or (v).

The script might demand portrayal of an amateur drug abuser incorrectly injecting a needle into an artery instead of a vein, and blood spurting out and hitting the roof. Such a scene is most likely to offend human sensibilities by depravity. It gets hit by a guideline which requires that in pursuance of the objectives, the CBFC shall ensure that human sensibilities are not offended by depravity. The objectives which come into play could be all or anyone of (i), (iv) or (v).

Well, every dark cloud has a silver lining.

The guidelines mandate that the CBFC shall also ensure that the film is judged in its entirety from the point of view of its overall impact and it is examined in the light of the period depicted in the films and the contemporary standards of the country and the people to which the film relates. However, this silver lining is also cursed with a dark cloud. The guidelines go on to say that the film should not deprave the morality of the audience.

Let me give you the example of a hypothetical film called Run.D, which is on rescuing prostitutes from Indian brothels.

The CBFC ensures that it is judged in its entirety from the point of view of its overall impact. It also ensures that it is examined in the light of the period depicted in the film and the contemporary standards of India and Indians.

Consequently, the CBFC finds the film to be adhering to the guidelines and their objectives. Despite coming so far, if in view of the CBFC, the film depraves the morality of the audience, then it would fall foul of the guidelines.

Say, the title of this hypothetical film i.e., Run.D indicates RUNNING away from a world where a prostitute is colloquially called a randi.The guidelines mandate that the CBFC shall scrutinise the titles of the films carefully and ensure that they are not provocative, vulgar, offensive or violative of the guidelines. When it comes to the title of a film, the guidelines do not specifically require the CBFC to judge it in its entirety from the point of view of its overall impact.

Moreover, vis-à-vis the title of a film, the guidelines do not specifically require the CBFC to examine it in the light of the period depicted in the films and the contemporary standards of the country and the people to which the film relates.

The title Run.D, in all likelihood, falls foul as, taken alone, it is vulgar and violative of the guidelines.

Mind you, the film Run.D is enduring all this at the hands of the CBFC and not at the hands of the audience. By the way, the audience has not even viewed the film.

I am talking about pre-censorship of films in India.

I am talking about what films endure at the hands of an Indian authority,which consists of persons whose qualification/s are unsaid and/or subjective.

All of this is done in India in the name of film certification. That’s where the problem lies.

Being a film in India is a curse.

The rules of 1983:

The Certification Rules, 1983, were made in supersession of the Cinematograph (Censorship) Rules, 1958 (Censorship Rules, 1958). Yes, you read it right, before Certification Rules, 1983, Censorship Rules, 1958 were in place, officially.

The Censorship Rules, 1958, contained no guidelines on certifying films. Those were silent on the eligibility criteria or the qualification/s to be appointed as members of CBFC.

You know what, despite the name, Censorship Rules, 1958, were not that bad. I say so, because, Censorship Rules, 1958, treated news reel and documentary separately from a feature film. Moreover, Censorship Rules, 1958, prescribed a separate examining committee for certifying documentaries, educational films and the like.

However, the Cinematograph Act, 1952, has not defined the word “documentary”. Even the Certification Rules, 1983, do not define the said word. More on documentaries later in this piece.

Coming back to the Certification Rules, 1983. Upon a bare perusal of these rules, it emerges that:

- The formation of an examining committee to examine a film for certification is envisaged. However, no qualification/s of members of such a committee has been specified.

- The formation of a revising committee to re-examine a film, which was earlier examined by the examining committee, is envisaged. However, no qualification/s of members of such a committee has been prescribed. Pertinently, no guiding principles have been laid down while re-examining films as well as certified films.

- No qualification/s has been specified in relation to members of an examining committee to be formed, for the purpose of alteration of films after issue of certificate.

With so many insignificant persons, insignificant in the sense that their qualification/s are non-existent and/or based on successive Central governments’ opinions that they are qualified to judge the effect of the films on the public, there is immense scope for errors.

The remedial forum:

Where does a filmmaker go when he is aggrieved by such errors? The Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT) is seemingly the light at the end of tunnel.

What if a filmmaker applies for certification of a film and CFBC passes an order:

- refusing grant of a certificate, or,

- directs him to carry out any excisions or modifications, or,

- grants only an “A” certificate, or,

- grants only a “S” certificate, or,

- grants only a “U/A” certificate

The Cinematograph Act, 1952, provides that an Appellate tribunal called FCAT shall hear appeals against such orders. It is located in New Delhi. The FCAT was constituted only in June 1983 i.e., after the Certification Rules, 1983, came into force in May 1983.

Appeals to the FCAT have to be made by a petition in writing. Along with such an appeal, a brief statement of the reasons for the order appealed against has to be furnished, if such a statement has been furnished to the aggrieved person.

Along with such an appeal, fees not exceeding Rs. 1,000 has to be paid, as may be prescribed.

Such an appeal is to be filed within 30 days from the date of the order. However, if the FCAT is satisfied that the aggrieved person was prevented by sufficient cause from filing the appeal within the 30 days, then, the delay can be condoned and the appeal can be taken up within a further period of 30 days.

As per the Cinematograph Act, 1952, FCAT is to consist of a chairman and not more than four members. The chairman and the members are appointed by the Central government. The said statute provides that the chairman of FCAT shall be a retired judge of a high court, or, is a person who is qualified to be a judge of a high court. The said prescription is in stark contrast with the provisions mentioned hereinabove, which are subjective and/or deficient as to the qualification/s. However, as regards the remaining members of FCAT, the said statute merely provides that the Central government may appoint such persons to be members of FCAT, who, in its opinion, are qualified to judge the effect of the films on the public. Even Certification Rules, 1983, do not stipulate any qualification/s of members of FCAT.

Regulation of the television broadcasting industry and the internet

Earlier in this piece, I had mentioned that today films cease to be a powerful medium of mass communication vis-à-vis the television broadcasting industry and the internet, however, they continue to be the most regulated. This regulation is to the extent that films, in India, are exposed to pre-censorship i.e., they are scrutinised before they are made public, however, in India, television content and internet content are not haunted by pre-censorship.

Content related aspects of the Indian television broadcasting industry are governed by the Cable Television Networks (Regulation) Act, 1995 (Cable Act) and the Cable Television Networks Rules, 1994 (Cable Rules). You can read more about these laws here.

The Cable Act and/or Cable Rules do not require the script/unedited footage/final programme or any other format to be subjected to inspection before it is made public. In other words, in India, television content is not subject to pre-censorship.

Internet in India is regulated by the Information Technology Act, 2000 (IT Act). The content uploaded on, for, or used to communicate with the viewers through the internet is not required to be certified prior to it being exhibited or presented. In other words, in India, internet content is not subjected to pre-censorship.

To put it simply, if the same Run.D were to have been a television show or shown on the internet, it would not have been pre-censored under Indian law.

The curious case of documentaries

At the outset, I must say that till date, the Cinematograph Act, 1952, has not defined the word “documentary”. Even the Certification Rules, 1983, have not gone on to define the word “documentary”. Yes, as mentioned earlier, the Censorship Rules, 1958, treated news reel and documentary separately from a feature film and they prescribed a separate examining committee for certifying documentaries, educational films and the like. However, Certification Rules, 1983, having replaced Censorship Rules, 1958, the distinction ceases to exist. A documentary, for the purpose of the Cinematograph Act, 1952, and Certification Rules, 1983, is just another film.

Documentaries, by their very nature, either portray real life incidents or recount details of any incident. The basis of such portrayal or recounting is facts. Facts should never be censored. Pre-censorship of facts is disturbing.

Television content as well as internet content is extensively dotted with editorials, investigative reports and news. In India, such content is not at the mercy of any authority for certification/scrutiny. It travels to the audience, freely. However, Indian documentaries of any nature whatsoever, which are obviously comparable with editorials, investigate reports and news, as they are also factual depictions, are haunted by pre-censorship, because, documentaries are films, as per Indian law.

Due to the very nature of documentaries, makers of documentaries often suffer a host of hardships while making them. It would not be out of place to mention that they frequently suffer monetary hardships too, while making documentaries. They are usually made on shoestring budgets. Documentaries are seldom made with a view to generate revenue. Critical acclaim apart, documentaries rarely generate revenue. In view of such compelling monetary reasons, ideally, there should be no requirement to pay any fees for certification of documentaries in India. However, in India, the fees required to be paid for certification of documentaries is the same as that for films which have budgets running into lakhs and crores of rupees.

A documentary called Run.D, which shows real rescue operations of prostitutes from brothels, interviews of prostitutes, pimps and rescuers is most likely to face greater travails at the hands of the CBFC. The makers of Run.D, the documentary, might not have the wherewithal to fight it through FCAT and other courts. A hard-hitting and well-researched documentary like Run.D might never get to see the light of the day.

If being a film in India is a curse, being a documentary in India is worse.

An ode to Shri ShyamBenegal, Shri Amol Palekar and Shri Utpal Dutt

The Ministry of Information & Broadcasting (MIB) formulates and administers Indian law relating to broadcasting, information and films. In January 2016, the MIB appointed a committee chaired by Shri Shyam Benegal to evolve guidelines and procedures for the benefit of the CBFC. In April 2016, the said committee submitted its report. Draft rules and guidelines were proposed while recommending amendments in some provisions of the Cinematograph Act, 1952. I hope and trust that the Government of India considers the recommendations and acts upon the same, in a manner that all the stakeholders in the film industry are benefited.

By way of a writ petition, Shri Amol Palekar has challenged the constitutional validity of provisions of the Cinematograph Act, 1952 and Certification Rules, 1983. Vide its order dated 17.04.2017, the Supreme Court was pleased to issue notice in the said writ petition to the MIB and the CBFC. The said writ petition is pending.

Do you feel that the times they are a changing? Do you feel that you gazed upon the chimes of freedom flashing?

I would like to end my piece with the following shloka, which is recited by Shri Utpal Dutt in this classic scene:

यदेतद्धृदयंतव

तदस्तुहृदयंमम।

यदिदंहृदयंमम

तदस्तुहृदयंतव॥

With a hope that the respective desires are the same, it could be read as:

Wherever your heart lies, may my heart lie there. Wherever my heart lies, may yours too.

Arjun Natarajan is an advocate. Regulation of broadcasting, information and films, in particular, interests him. He is the publishing editor of a blog founded by him, called www.onthesidelinesofgpcseriesindia2017.wordpress.com

[The opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of LiveLaw and LiveLaw does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same].