"Tofan Singh's Case" Opens Up New Horizons In The Law Of "Confessions" In Criminal Trials

Justice V Ramkumar

23 Nov 2022 9:18 AM IST

(This is the text of a webinar lecture which the author had made in a lawyers' collective.)

I begin this lecture with my usual caveat that I am not an expert in criminal law. I am only a "facilitator" who is willing to share his experience and knowledge with you in the expectation of learning a lot from you in return. Even at the december of my life, I have no roses to offer and I still consider myself a student of law and I will continue to be so till my last breath.

2. I am following a different methodology. I don't believe in giving an abstract lecture on any subject only to be forgotten by the listeners without doing any practical exercise. Any law is better understood when applied to concrete facts situations. That explains my questions.

3. Today we are proposing to examine the impact of Tofan Singh v. State of Tamil Nadu (2021) 4 SCC 1 - Rohinton F. Nariman, Navin Sinha, Indira Banerjee – JJ, on the law of confessions, particularly Sections 25 and 26 of the Indian Evidence Act. Let me frankly confess that I have not gone through the entire judgment which runs into 219 pages and 428 paragraphs. The startling prolixity of Keshavanand Bharati (1973) 4 SCC 225 – 13 Judges - S. M. Sikri –CJI, J. M. Shelat, K. S. Hegde, A. N. Grover, A. N. Ray, P. Jaganmohan Reddy, D. G. Palekar, H. R. Khanna, K. K. Mathew, M. H. Beg, S. N. Dwivedi, A. K. Mukherjea, Y. V. Chandrachu – JJ, had been an unwelcome and unwieldy feature among the legal fraternity. There seems to be a re-emergence of that trend. Gautam Navlakha's case pronounced on 12-05-2021 is another recent prolific Judgment running into 206 pages in which a new "Judge-made" custody by way of "house arrest" other than the hitherto judicially recognized "Police and Judicial custody", has been saddled on the Executive by the Apex Court. At this rate, one day, a litigant may tell the Apex Court (of course, at his own peril) that prolixity of Judgments affects his right to information and thereby his right to life guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution of India. Regrettably, we come across such verdicts now-a-days.

4. In Tofan Singh the question was whether officers invested with powers under Section 53 of the NDPS Act could be treated as "police officers" within the meaning of Section 25 of the Evidence Act and whether any confessional statement made to them by an accused person would be hit by Sections 25 or 26 of the Evidence Act. The case came before a three-Judge Bench upon a reference by a Bench of 2 Judges. The majority of 2 Judges speaking through Justice Rohinton F. Nariman answered the reference in the affirmative holding that those officers could answer the description of "police officers" under Sections 25 and 26 of the Evidence Act. Justice Indira Banerjee found herself unable to agree with the above view and she answered the reference in the negative.

5. If you pronounce it as "Toofan", it means in Hindi a "storm". Yes indeed, this verdict from the majority has taken the entire legal fraternity by storm. If you pronounce it as "Tofan", treating the "n" as silent, it means "gift". You can consider it as a surprise gift for the posterity to ponder over. While in the realm of stare decisis, it violates the basic canons of judicial precedents in the development of law, it makes a welcome departure giving meaningful and posthumous recognition to the dissenting view of late Justice K. Subba Rao in State of Punjab v. Barkat Ram AIR 1962 SC 276 = 1962 (1) Cri.L.J. 217 – 3 Judges, rendered on 30-08-1961. The author of the present "majority view" is an expert acrobat in surmounting binding precedents. We have other examples by the same author in Vinubhai Haribhai's case AIR 2019 SC 5233 - Rohinton F. Nariman; Surya Kant; V. Ramasubraman - JJ; Arjun Panditrao Khotkar's case AIR 2020 SC 4908 – Rohinton F. Nariman, S. Ravindra Bhat, V. Ramasubramanian - JJ; M. P. Steel Corporation (2015) 7 SCC 58 – A. K. Sikri, Rohinton F. Nariman – JJ etc. But, it is an undisputable fact that the said author is a jurist par excellence. In the context of stare decisis, my respectful opinion is that the dissenting view of Justice Indira Banerjee undoubtedly takes the correct precedential approach. When Benches of co-ordinate or lesser strength propose not to follow the beaten track, they can venture to do so only after a reference of the matter to a larger Bench for an authoritative pronouncement of the law. The majority view in Tofan Singh's case (Supra - (2021) 4 SCC 1) suffers from this procedural infraction. But, on the question as to who is a "police officer" for the purpose of Section 25 of the Evidence Act, the majority view, in my humble opinion, has cleared the path possibly for a binding verdict in future and thereupon it will immortalise the dissenting verdict of Justice K. Subba Rao in Barkat Ram's case (Supra - AIR 1962 SC 276) to be adverted to later.

6. Now let us discuss a few questions on the topic.

Q.1 What is a confession and when does a statement amount to a confession?

Ans. The expression "confession" has not been defined in the Evidence Act. A statement in order to be a confession must either admit in terms the offence, or at any rate substantially all the facts which constitute the offence. An admission of an incriminating fact, howsoever grave, is not by itself a confession. A statement which contains an exculpatory assertion of some fact, which if true, would negative the offence alleged, cannot amount to a confession (Vide Pakala Narayana Swami v. Emperor. AIR 1939 PC 47 – Lord Atkin; Palvinder Kaur v. State of Punjab AIR 1952 SC 354 – 3 Judges – Mehr Chand Mahajan, N. Chandrasekhara Aiyar, N. H. Bhagwati - JJ; Om Prakash v. State of U.P AIR 1960 SC 409 – A. K. Sarkar, M. Hidayatullaj - JJ; Veera Ibrahim v. State of Maharashtra (1976) 2 SCC 302 – R. S. Sarkaria, N. L. Untwalia – JJ );

Sahoo v. State of U.P. AIR 1966 SC 40 = 1966 Cri.L.J. 68 – 3 Judges - K. Subba Rao, J. C. Shah, R. S. Bachawat - JJ. (In paras 5 and 6 held that "Soliloquy" (muttering to oneself) of the accused admitting his guilt if overheard by another can be an instance of extra-judicial confession that may be admissible, but regarding the weight to be attached to it, it may be used only as a corroborative piece of evidence).

Q.2 Is oral confession by an accused person, "evidence" within the meaning of Section 3 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872?

Ans. No. The definition of "evidence" in Section 3 takes in only oral statements which a Court permits or requires to be made before it by witnesses and documents including "electronic records" produced for the inspection of the Court. The said definition does not take in a "confession" by the accused. (Vide Kashmira Singh v. state of M.P AIR 1952 SC 159 – 3 Judges - Saiyid Fazl Ali, B. K. Mukherjea, Vivian Bose- JJ; HaricharanKurmi and Another v. State of Bihar AIR 1964 SC 1184 – 5 Judges - P. B. Gajendragadkar – CJ, K. N. Wanchoo, K. C. Das Gupta, J. C. Shah, N. Rajagopala Ayyangar - JJ).

The definition of the word "evidence" in Section 3 of the Evidence Act takes in only oral and documentary evidence including electronic records. The following do not strictly fall under the said definition of "evidence":-

- Confession by the accused.

- Statement made by the accused during trial including Section 313 statement.

- Notings made by the Judge regarding the demeanour of a witness under examination in Court.

- The result of local inspection made by the Court under Section 310 Cr.P.C.

- Material objects.

The above will fall under the expression "matters" in the definition of the word "proved" in Section 3 of the Evidence Act. Material object may also fall under the expression "material thing" under the second proviso to Section 60 of the Evidence Act.

Q.3 Where a part of the statement by the accused is inculpatory and another part exculpatory, is not the prosecution entitled to request the Court to use the inculpatory part of the statement?

Ans. No. The whole of such statement should be tendered in evidence. The inculpatory part alone cannot be used by the prosecution. (Vide Agnoo Nagesia v. State of Bihar AIR 1966 SC 119 - K. Subba Rao, Raghubar Dayal, R. S. Bachawat - JJ; State of U.P. v. Deoman Upadhyaya AIR 1960 SC 1125; Kanda Padayachi v. State of T.N. AIR 1972 SC 66 – J. M. Shelat, I. D. Dua, S. C. Roy – JJ.

NOTE BY VRK: But in Nishi Kant Jha v. State of Bihar AIR 1969 SC 422 – 5 Judges – Hidayatullah – CJI, Shah, Ramaswami, Mitter, Grover - JJ, where a statement by the accused recorded by a Village Mukhia falling under Section 24 was containing both inculpatory and exculpatory parts, it was held that the exculpatory part was not only inherently improbable but was also contradicted by other evidence justifying rejection of the exculpatory part and acceptance of the inculpatory part.

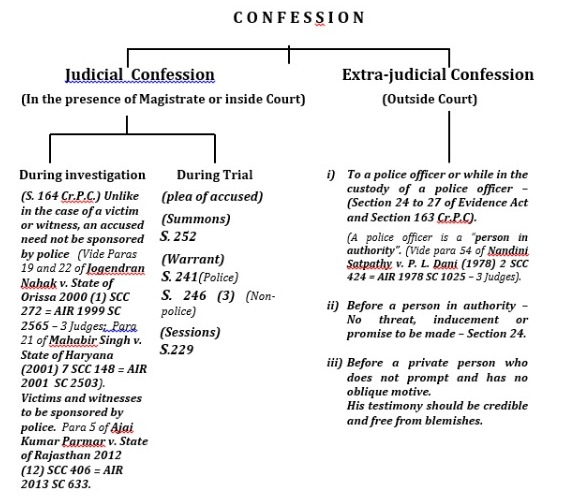

Q.4 How can confession be classified?

Ans. Confession may be broadly classified into two:-

NOTE BY VRK: (The role, if any, of the police while the "accused" is making a confession under Section 164 (4) Cr.P.C. and while a "victim" or "witness" is giving a statement under Section 164 (5) Cr.P.C., should be taken note of.)

Statements of witnesses & victims under Section 164 (5) Cr.P.C are to be recorded in camera, but not the confessions given by the accused. (Vide Varghese M.U. v. CBI, Cochin 2015 (3) KLT 54 – K. Abraham Mathew - J)

Q.5 A confession is recorded by an Executive Magistrate under Sec. 164 Cr.P.C. Is it totally inadmissible in evidence ?

Ans. Yes. As per Sec. 164 Cr.P.C., a Judicial Magistrate alone can record a confession. (Vide Asst. Collector of Central Excise v. Duncun Agro Industries Limited- AIR 2000 SC 2901 – K. T. Thomas, R. P. Sethi - JJ).

NOTE BY VRK: But an Executive Magistrate or any person in authority can take an extra judicial confession which must, however, satisfy the test of Section 24 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872.

Q.6 Since Sections 24 to 27 of the Evidence Act refer to "a person accused of any offence", should not the person making the confession be an accused at the time of making the confession ?

Ans. No. The person making the confession need not be an accused at the time of making the confession. The expression "accused person" occurring in Section 24 and the expression "person accused of an offence" occurring in Sections 25 and 27, is only descriptive of his subsequent status and it is sufficient if at the time of making the confession, criminal proceedings were in prospect. (Vide Pakala Narayana Swamy v. Emperor AIR 1939 PC 47– Lord Atkin, which was followed in para 7 of State of U.P. v. Deoman Upadhyaya AIR 1960 SC 1125 – 5 Judges - S. K. Das, J. L. Kapur, K. Subba Rao, M. Hidayatullah, J. C. Shah - JJ; Bheru Singh v. State of Rajasthan (1994) 2 SCC 467 - Dr. A. S. Anand, Faizan Uddin - JJ).

The words "accused of any offence" in Section 25 would cover the case of an accused who has since been put on trial, whether or not at the time when he made the confessional statement, he was under arrest or in custody as an accused in that case. (Vide Bheru Singh v. State of Rajasthan (1994) 2 SCC 467).

NOTE BY VRK: In sharp contrast, for the bar against testimonial compulsion under Article 20 (3) of the Constitution of India to apply, there should be a formal accusation against the person. Such formal accusation may either be in the form of registration of FIR or the filing of a complaint. (Vide M. P. Sharma v. Sathish Chandra, District Magistrate, Delhi AIR 1954 SC 300 – 8 Judges - Mehr Chand Mahajan – CJI, B. K. Mukherjea, S. R. Das, Vivian Bose, Ghulam Hasan, N. H. Bhagwati, B. Jagannadhadas, T. L. Venkatarama Ayyar - JJ; Raja Narayanlal Bansilal v. Maneck AIR 1961 SC 29 – 5 Judges – B. P. Sinha – CJI, P. B. Gajendragadkar, K. N. Wanchoo, K. C. Das Gupta, J. C. Shah - JJ; Paras 75 to 81 of Directorate of Enforcement v. Deepak Mahajan AIR 1994 SC 1775 – S. Ratnavel Pandian, K. Jayachandra Reddy - JJ; State of Bombay v. Kathi Kalu Oghad AIR 1961 SC 1808 – 11 Judges - B. P. Sinha – CJ, S. J. Imam, S. K. Das, Gajendragadkar, A. K. Sarkar, Subba Rao, Wanchoo, Das Gupta, Dayal, Rajagopala Ayyangar, Mudholkar -JJ; Nandini Satpathy v. P. L. Dani (1978) 2 SCC 424 = AIR 1978 SC 1025 - V. R. Krishna Iyer, Jaswant Singh, V. D. Tulzapurkar - JJ.)

Likewise, a person whose statement is recorded under Section 108 of the Customs Act, 1962 is not an accused at that stage. He becomes an accused only when summons is issued to him by a competent Court. (Vide K.I.Pavunni v. Asst. Collector (HQ), Central Excise Collectorate (1997) 3 SCC 721 = 1997 (1) KLT 489 (SC) – 3 Judges - K. Ramaswamy, S. Saghir Ahmad, G. B. Pattanaik – JJ.)

Q.7 A person who is subsequently made an accused on a charge of "uxoricide" (killing one's wife) and who is not in custody tells a police officer that the charred body of his wife is lying in the rear courtyard of his house. Can the above statement be proved against him, in view of Section 25 of the Evidence Act ?

Ans. Yes, because it is only an admission and not a confession. For the interdict under Section 25 to operate, there has to be a confession. In order to constitute a confession it must either admit in terms the offence or at any rate substantially all the facts which constitute the offence. (Vide Pakala Narayana Swami (supra AIR 1939 PC 47 – Lord Atkin; Palvinder Kaur v. State of Punjab AIR 1952 SC 354 – 3 Judges - Mehr Chand Mahajan, N. Chandrasekhara Aiyar, N. H. Bagwati - JJ; Om Prakash v.State of U.P. AIR 1960 SC 409 – A. K. Sarkar, M. Hidayatullah - JJ; Sahoo v. State of U.P. AIR 1966 SC 40 – 3 Judges – K. Subba Rao, J. C. Shah, R. S. Bahcawat - JJ).

But, if the statement was that he murdered his wife by pouring kerosene on her body and setting her ablaze and that her charred body is lying in the rear courtyard of his house, then the admission cannot be dissected or divorced from the inculpatory part of the statement so as to admit the non-inculpatory part alone. Court has to accept or reject the statement as a whole (See Palvinder Kaur (Supra – AIR 1952 SC 354).

It has already been seen in the previous question that while in the case of the right against testimonial compulsion guaranteed under Article 20 (3) of the Constitution of India, there should be a formal accusation either in the form of an FIR or a complaint, in the case of Sections 24 to 27 of the Evidence Act there is no need for any formal accusation at the time of making the statement to the person in authority including the police.

While all confessions are admissions, all admissions need not necessarily be confessions.

Q.8 What is the decisive test for holding whether the Officer concerned is a "Police Officer" within the meaning of Section 25 of the Indian Evidence Act ?

Ans. Section 25 of the Evidence Act reads as follows:-

"25. Confession to police officer not to be proved.

No confession made to a police officer shall be proved as against a person accused of any offence".

For holding whether a person is a "police officer" or not, the preponderance of judicial opinion so far has been the following :-

Even if, under a particular statute, an officer is invested with the power of an "officer-in-charge of a police station", that will not make him a "police officer" unless –

1. powers are conferred on him for the detection and prevention of crime and for bringing the offender to book, and not merely for the purpose of either ensuring that dutiable goods do not enter the country, or to prevent the smuggling of contraband goods into the country.

A N D

2. he is also empowered to conduct investigation as per the Cr.P.C. and is invested with the authority to file a "police report" under Section 173 (2) Cr.P.C.

A The first of the above propositions as aforesaid was laid down in –

1) State of Punjab Vs. Barkhat Ram AIR 1962 SC 276 - 3 Judges. - J. L. Kapur, K. Subba Rao & Raghubar Dayal – JJ).

The majority view was rendered by Raghubar Dayal – J for himself and also for J. L. Kapur – J.

There, the question was as to whether a "Customs Officer" acting either under the Land Customs Act, 1924 or under the Sea Customs Act, 1878 or under the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act, 1947 ("FERA" for short) could be treated as a "police officer" within the meaning of Section 25 of the Indian Evidence Act. The majority consisting of J.L. Kapur & Raghubar Dayal J.J. held that the "Customs Officer" cannot be treated as a "police officer". But, Justice K. Subba Rao gave a dissenting opinion.

THE MAJORITY VIEW

The majority Judges, inter alia, held as follows:-

a) While the powers conferred on the "police officers" are for the prevention and detection of crime, the powers conferred on the Customs Officers are merely for the purpose of ensuring that dutiable goods do not enter the country without payment of duty and that articles whose entry is prohibited are not brought in. The power of search of the property and person and the power to detain persons or to summon persons to give evidence in an inquiry etc. conferred on the Customs Officers, is for detecting and preventing of the smuggling of goods and loss to the central revenues (Para 10).

b) Since the definition of the expression "police" in the Police Act, 1861(Central Act V of 1861) is an inclusive definition, persons other than those enrolled under the said Act can also be covered by the word "police" (Para 13…………………………………….)

The expression "police officer" is not restricted to police officers of the police forces enrolled under the Police Act, 1861. A person who is a member of the police force under the Police Act, 1861 will also be a member of the police force when he holds his office under any of the enactments dealing with the police (Para 13).

c) The words "police officer" are not to be construed in a narrow way, but have to be construed in a wide and popular sense as was remarked in Queen v. Hurribole, ILR 1 Cal. 207 where a Deputy Commissioner of Police who was actually a police officer but was merely invested with certain Magisterial powers was held to be a "police officer" within the meaning of Section 25 of the Evidence Act (Para 16).

|

e) The acquittal by the High Court by excluding the confession made to the Customs Officer is bad and the conviction by the Magistrate, as confirmed by the Sessions Judge, is restored.

f) Strangely observes in para 29 as follows :-

"29. We make it clear, however, that we do not express any opinion on the question whether officers of departments other than police, on whom the powers of an officer- in-charge of a police station under Chapter XIV of the Code of Criminal Procedure, have been conferred, are police officers or not for the purpose of S. 25 of the Evidence Act, as the learned counsel for the appellant did not question the correctness of this view for the purpose of this appeal".

DISSENTING VIEW OF JUSTICE SUBBA RAO

Justice Subba Rao found himself unable to agree with the majority view. The following are, inter alia, the reasons given by Justice Subba Rao :-

a1) Considering the powers of the Customs Officer under the statutes in question, the power given for "search and seizure", "arrest", obtain a "confession", to "summon persons" to give "evidence" etc. are undoubtedly for the purpose of prevention and detection of offences. The High Court, therefore, was right in excluding the confession made to the Customs Officer and since de hors the said confession, there was no other material against the accused, the High Court was right in acquitting the accused. (Vide para 40).

a2) The salutary principle underlying Section 25 would apply equally to other officers (by whatever designation they may be known) who have the power and duty to detect and investigate into crimes and is for that purpose in a position to extract confessions from the accused (vide para 33).

An officer (by whatever designation he is called) on whom a statute substantially confers the powers and imposes the duties of the police, is a police officer within the meaning of Section 25 of the Evidence Act." (Vide para 39).

|

2) Rajaram Jaiswal v. State of Bihar AIR 1964 SC 828 – 3 Judges - K. Subba Rao, Raghubar Dayal, J. R. Mudholkar – JJ, was a three-Judge Bench consisting of K. Subba Rao, Raghubal Dayal and R. Madholkar-JJ. The majority Judges (R. Madholkar – J & K. Subba Rao) referring to earlier decisions including Barkat Ram held that confession made to an "Excise Inspector" under the Bihar and Orissa Excise Act, 1915, is hit by Section 25 of the Evidence Act since it is the power of investigation given to that officer for collection of evidence which would make him a "police officer". The majority took into account the fact that as per the provisions of the Bihar and Orissa Excise Act, 1915, the Excise Officer empowered under Section 77 thereof could exercise all the powers which an officer-in-charge of a police station can exercise under Chapter XIV of Cr.P.C., that he could investigate into offences, record statements of persons questioned by him, make searches, seize any articles connected with an offence under the said Act, arrest an accused person, grant him bail, send him up for trial before a Magistrate, file a charge-sheet and so on. Referring to Barkat Ram it was observed in para 15 of the Judgment that even the majority in Barkat Ram had clearly held that the expression "police officer" used in Section 25 of the Evidence Act is not to be construed in a narrow way.

Notices in paragraph 9 that the majority in Barkat Ram, however, expressed no opinion on the question whether officers of departments other than the police on whom the powers of an officer-in-charge of a police station under Ch. XIV of the Code of Criminal Procedure are conferred are police officers or not for the purpose of S.25 of the Evidence Act. The question whether an Excise Officer is a Police Officer was thus left open by them.

|

B Thereafter the uniform test applied by the Supreme Court is that even if an Officer is invested with the powers of an Officer-in-charge of a Police station under a special statute, he does not become a Police Officer unless he is also empowered to file a "police report" under Section 173 (2) Cr.P.C. – (Vide –

3) Badaku Joti Savant v. State of Mysore AIR 1966 SC 1746 – 5 Judges – P. B. Gagendragadkar, CJI, K. N. Wanchoo, M. Hidayatullah, J. C. Shah. S. M. Sikri - JJ (Justice K. N. Wanchoo speaking for the Constitution Bench (comprising also of P. B. Gajendragadkar-CJI, M. Hidayatullah, J. C. Shah, S. M. Sikri – JJ) held that the Deputy Spdt. of Customs and Excise functioning under the Sea Customs Act, 1878 and the Land Customs Act, 1924, is not a "police officer" – also held that the report filed by the Central Excise Officer under the Central Excise and Salt Act, 1944, is not a "police report" under Clause (b) of Section 190 (1) Cr.P.C. and that he can file only a "complaint" under Clause (a) of Section 190 (1) (a) Cr.P.C.) (Barkat Ram followed and Raja Ram Jaiswal distinguished on the ground of different statutory settings).

4) A three - Judge Bench in Romesh Chandra Mehta v. State of W.B. AIR 1970 SC 940 - 3 Judges – J. C. Shah, Ramaswami, Grover - JJ. Held that a Customs Officer acting under the Sea Customs Act, 1878, (which is the very same statute considered in Barkat Ram) is not a member of the police force, that he cannot be deemed to be a police officer who is entitled to submit a report under Section 173 Cr.P.C. and that any confession made to him will not be hit by Section 25 of the Evidence Act. The majority view in Barkat Ram and the decision of the Constitution Bench in Badaku Joti Savant, were, inter alia, relied on.

5) Illias v. Collector of Customs AIR 1970 SC 1065 – 5 Judges - J. C. Shah, V. Ramaswami, G. K. Mitter, K. S. Hegde, A. N. Grover –JJ, speaking through Justice A. N. Grover held that a Customs Officer under the Customs Act, 1962 is not a "police officer" within the meaning of Section 25 of the Evidence Act. In paragraph 4 observes that a three-Judge Bench in P. Shankar Lal v. Asst. Collector of Customs 1968 SCD 385 – 3 Judges – M. Hidayatullah, S. M. Sikri, K. S. Hegde – JJ, has held that there is no conflict between Raja Ram Jaiswal AIR 1964 SC 828 - K. Subba Rao, Raghubar Dayal, J. R. Mudholkar - JJ and Barkat Ram AIR 1962 SC 276 - J. L. Kapur, K. Subba Rao, Raghubar Dayal – JJ, the absence of a power to file a "police report" was also highlighted).

(NOTE by VRK: Actually there is a conflict between the two rulings). This decision has to be examined in the light of Noor Aga (2008) 16 SCC 417 – S. B. Sinha, V. S. Sirpurkar - JJ.

6) Balkishan A Devidayal v. State of Maharashtra AIR (1980) 4 SCC 600 = AIR 1981 SC 379 - Sarkaria & Chinnappa Reddy - JJ – Held that an Officer of Railway Protection Force exercising powers under the Railway Property (Unlawful Possession) Act, 1966 is not a "police officer" – Barkat Ram & Badaku Joti Savant followed and Raja Ram Jaiswal was distinguished. The absence of a power to file a "police report" under Section 173 Cr.P.C. was also highlighted).

7) Raj Kumar Karwal v. Union of India (1990) 2 SCC 409 = AIR 1991 SC 45 - A.M.Ahmadi & M.Fathima Beevi – JJ. Held that Officers of the Department of Revenue Intelligence – ("DRI" for short), exercising powers under Section 53 of the NDPS Act, 1987 are not "police officers" – follows Baduku Joti Savant which had distinguished Barkat Ram and Raja Ram Jaiswal). Also notices the absence of power to file a "police report". (Forgets that NDPS Act is a penal statute and the officer of DRI was investigating).

8) Directorate of Enforcement v. Deepak Mahajan (1994) 3 SCC 440 = AIR 1994 SC 1775- S. Ratnavel Pandian & K.Jayachandra Reddy - JJ. Held that Officer of the Enforcement Directorate arresting an offender under Section 35 (1) of the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act, 1973 ("FERA" for short) which is pari materia with Section 104 (1) of Customs Act, 1962 is not a "police officer"); After noticing the powers of investigation of the Officer of the Enforcement Directorate and of the Customs Officer under the Customs Act, 1962, the Bench observed in paragraphs 115 to 119 that the word "investigation" cannot be limited only to police investigation. The Bench further observed that an Officer as aforesaid is also invested with the power of "investigation".

|

|

9) Abdul Rashid v. State of Bihar (2001) 9 SCC 578 = AIR 2001 SC 2422 – G. B. Pattamaik,, U. C. Banerjee – JJ. A two- Judge Bench of the Supreme Court (G. B. Pattanaik & U. C. Banerjee – JJ) following the majority view in Rajaram Jaiswal's case (AIR 1964 SC 828) held that the Superintendent of Excise exercising powers under the Bihar and Orissa Excise Act, 1915, is a "police officer" within the meaning of Section 25 of the Evidence Act and any confession made to him will be hit by Section 25 of the Evidence Act. (Same statute in both the decisions).

10) Francis Stanley @ Stalin v. Intelligence officer, Narcotic Control Bureau (2006) 13 SCC 210 = AIR 2007 SC 794 - S.B.Sinha & Markandeya Katju – JJ – Para 15 – held that even though confession made to an officer of DRI under NDPS Act is not hit by Section 25 of the Evidence Act, such confession must be subjected to closer scrutiny than a confession made to officials who do not have investigating power under the statute………. ultimately, the confession made in the case was not accepted by the Supreme Court.

|

12) Kanhayalal v. Union of India (2008) 4 SCC 668 = AIR 2008 SC 1044 - Altamas Kabir & B. Sudershan Reddy – JJ. Here the question was whether a confession made to an officer of the Central Bureau of Narcotics under Section 67 of the NDPS Act, 1985 was hit by Section 25 of the Evidence Act. The two–Judge Bench answered the question in the negative to hold that he is not a "police-officer" by following the earlier verdicts to that effect including Raj Kumar Karwal.

It is pertinent to note in this connection that the settled legal position that unlike in the case of Article 20 (3) of the Constitution of India, for the interdict under Sections 24 to 27 of the Evidence Act to operate, the person making the confession need not formally be accused of the offence at that time and the words "person accused of an offence" in those Sections is only descriptive of his subsequent status, appears to have been overlooked. (This was discussed under Question No.6 above)

13) Ram Singh v. Central Bureau of Narcotics (2011) 11 SCC 347 = AIR 2011 SC 2490 - Harjit Singh Bedi & C. K. Prasad – JJ. Held that an Officer of Central Bureau of Narcotics dealing with an offence under NDPS Act, 1985 is not a "police officer").

Same view as in Kanhayalal. Forgets that the officer was conducting investigation of an offence under the NDPS Act.

14) Nirmal Singh Pehlwan @ Nimma v. Inspector of Customs, Customs House, Punjab (2011) 12 SCC 298 = 2011 KHC 4698 - H.S.Bedi & Gyan Sudha Misra – JJ). A two-Judge Bench of the Supreme Court held that a confession made to a Customs Officer under Section 108 of the Customs Act, 1962 admitting his guilt for the offence under Section 22 of the NDPS Act, 1985 was hit by Section 25 of the Evidence Act. The Bench found Noor Aga v. State of Punjab (2008) 16 SCC 417 = 2008 KHC 5054 – S. B. Sinha, v. S. Sirpurkar – JJ, preferable to Kanhayalal's case (Supra - AIR 2008 SC 1044) which, according to the Bench, had not examined the principles and concepts underlying Section 25 of the Evidence Act vis-à-vis Section 108 of the Customs Act. An interesting aspect of Nirmal Singh Pehlwan (Supra - (2011) 12 SCC 298) is that Justice H.S. Bedi was a party to this verdict as well as to the conflicting verdict in Ram Singh (Supra - AIR 2011 SC 2490).

|

NOTE by VRK: The majority view has virtually resurrected the dissenting view of Justice K. Subba Rao in Barkat Ram by heavily relying on Raja Ram Jaiswal AIR 1964 SC 828 – 3 Judges - K. Subba Rao, Raghubar Dayal, J. R. Mudholkar - JJ, giving stress on the power of investigation in the officer concerned.

Even though I am happy over this majority view, I am unhappy in the manner in which binding precedents have been overlooked for arriving at the above view.

Such a course, if adopted by the highest Court in the country, may defeat the primary object of predictability, certainty and finality expected of judicial pronouncements. The High Courts and the subordinate Courts will be in a state of utter confusion as to which of the conflicting verdicts are to be followed. The position was beautifully explained by Justice G. S. Singhvi in para 90 of Official Liquidator v. Dayanand (2008) 10 SCC 1 – 3 Judges - B. N. Agrawal, Harjit Singh Bedi, G. S. Singhvi - JJ, as follows:-

"Predictability and certainty is an important hallmark of judicial jurisprudence developed in this country in the last six decades and increase in the frequency of conflicting judgments of the superior judiciary will do incalculable harm to the system inasmuch as the Courts at the grass root will not be able to decide as to which of the judgments lay down the correct law and which one should be followed")

I am, however, a great admirer of Justice Rohinton Nariman who is a great "treasure house" of forensic knowledge.

MY FINAL OPINION

My final take on this subject is that "a person in authority" including a "police officer" covered by Section 24 of the Evidence Act, if invested with the power of "investigation" including the power to "summon persons to give statements" and powers of "search & seizure", "arrest", extract a "confession", etc. for the purpose of detection and prevention of crime and the power "to bring the offenders to justice" by either filing a "complaint" or a "police report", he is a "police officer" to whom a confession will be tabooed both under Sections 25 and 26 of the Evidence Act. Such a "person in authority" can definitely produce an "arrested person" before the Magistrate concerned under Section 167 (1) Cr.P.C. in view of Deepak Mahajan's case (Supra – AIR 1994 SC 1775).

"NOTE BY VRK: There is a misconception among some members of the legal fraternity that Section 167 Cr.P.C. enables only a "police officer" to produce an accused before a Magistrate seeking an order of detention to "Judicial" or "police" custody. It is not so. Section 167 Cr.P.C. not only speaks of "a police officer making the investigation", but also "the officer in charge of the police station". The second alternative takes in non-police officers who are invested with the powers of investigation similar to police officers.

Q.9 A confession is made to a DySP of police who is posted in the police canteen for placing orders from various manufacturers. The officer is neither discharging any police duty nor investigating any case. Is the confession hit by Section 25 of the Evidence Act ?

Ans. Yes. The Police Officer need not be the officer investigating the offence of which the person is subsequently made an accused. Such officer need not be discharging any police duty. Confession made to any member of the police of whatever rank and at whatever time is inadmissible in evidence. (Vide para 19 of State of Punjab Vs. Barkhat Ram AIR 1962 SC 276 - 3 Judges - J. L. Kapur, K. Subba Rao, Raghubar Dayal - JJ). See also Illias Vs. Collector of Customs AIR 1970 SC 1065 - 5 Judges - J. C. Shahl, V. Ramaswami, G. K. Mitter, K. S. Hegde; A. N. Grover - JJ ).

|

|

NOTE BY VRK: If a confession made to a police officer of whatever rank and at whatever time, whether he is doing any police duty or not, attracts the embargo under section 25 of the Evidence Act, then the above view in Raj Kumar Karwal and Francis Stanley contradicts with the prevailing view that in order to be a "police officer", he should also have the authority to file a "police report".

In Seethamaniyan v. State of Kerala 1996 (1) KLT 313 1996 Cri.L.J. 3038 – K. G. Balakrishnan, S. Krishnan Unni – JJ, it was held that a confession made to an IPS officer holding only an administrative post having no authority to conduct investigation, will not be hit by Section 25 of the Evidence Act.

(This decision, according to me, lays down the law correctly.)

Q.10 Is confession made to an Abkari Officer under the Kerala Abkari Act, 1077 ME hit by Section 25 of the Evidence Act ?

Ans. Yes. Now after the amendment of Section 50 of the Kerala Abkari Act with effect from 03-06-1997, the Abkari Officer is empowered to file before Court, a final report under Section 173(2) Cr.P.C. Abkari Officers who were hitherto filing complaints before the Court have been statutorily directed to file a police report under Section 173(2) Cr.P.C thereby making them police officers with effect from 03-06-1997. (Vide Joseph v. State of Kerala 2009 (2) KLD 915 = 2009 (4) KHC 537 – V. Ramkumar – J; Rajaram Jaiswal (Supra - AIR 1964 SC 828) - K. Subba Rao, Raghubar Dayal, J. R. Mudholkar - JJ, squarely applies.

NOTE BY VRK: This is an anomalous situation where a "non-police officer", as generally understood, becomes a "police officer" on account of the investiture in him the power to submit a "police report".

|

Q.11 Is confession made to a police officer who by virtue of Section 22 of the Transplantation of Human Organs Act, 1994, (the "TOHO Act" for short) statutorily prohibited from filing a police report under Section 173(2) Cr.P.C, admissible ?

|

NOTE BY VRK: Take also the case of an SHO who files a "complaint" under the Explanation to Section 2(d) Cr.P.C. consequent on his discovering that the offence which is really made out is a "non-cognizable offence" as against a "cognizable offence" which was initially alleged. Here also, can it be said that if the SHO who is a police officer, records a confession, it will not be hit by Section 25 of the Evidence Act merely for the reason that what he has filed before the Court is only a "complaint" ? Of course, not.

In Jeeven Kumar Raut v. CBI (Supra - AIR 2009 SC 2763) the Supreme Court has judicially noticed the fact that under Section 22 of the TOHO Act, the police officer is statutorily prohibited from filing a police report and is obliged only to file a complaint. (But strangely enough, the Apex Court has held in that decision that since the police officer can file only a complaint, sub-section (2) of Section 167(2) Cr.P.C is not applicable. If Section 167(2) Cr.P.C does not apply, the Magistrate cannot then remand the accused to any custody and even if he has remanded the accused to judicial custody, the provision for default bail also will not apply. It is submitted that this decision has overlooked the legal position that non-police officers invested with the power of officers-in-charge of a police station are not debarred from arresting an accused person and producing him before the Magistrate with a remand report and the Magistrate is also not debarred from remanding the accused to custody under Section 167(2) Cr.P.C. (Vide Directorate of Enforcement v. Deepak Mahajan AIR 1994 SC 1775 – Ayoob v. Superintendent of Customs Intelligence Unit 1984 KLT 215; C.I.U. Cochin v. P. K. Ummerkutty, 1983 CriLJ 1860, both by Justice U. L. Bhatt of the Kerala High Court, approved in para 103.)

Thus, it is not the power to file a "police report" which is decisive.

Q.12 Is not the accused entitled to take shelter under Section 25 of the Evidence Act to plead that a police officer cannot interrogate him for taking a confessional statement from him ?

Ans. No. Even though confession made by an accused to a police officer is not to be proved against him and cannot, therefore, be made use of for convicting the accused, it can nevertheless be a source of information for the police to put the criminal law into motion. (Vide para 29 of Pawan Kumar @ Monu Mittal v. State of U.P – (2015) 7 SCC 148 = AIR 2015 SC 2050).

NOTE BY VRK: This verdict may perhaps go to the rescue of the police to justify the acts of intensive interrogation (but not torture). If the manner of committing the crime on the victim is exclusively within the special knowledge of the accused and if there are no eye witnesses to the occurrence, then the accused alone can tell the police as to how he committed the crime. The answer by the accused regarding the manner of perpetrating the crime is certainly not admissible, but it ensures the police that the investigation is proceeding on proper lines.

Q.13 Is not the word "confession" in Section 25 of the Evidence Act confined to confession of the offence which is under investigation ?

Ans. No. The spirit of Section 25 of the Evidence Act is to exclude all confession to the police whether in the same crime or different crime. (Vide Kodangi v. Emperor – AIR 1932 Madras 24; In re Elukuri Seshapani Chetti AIR 1937 Madras 209).

Section 26

(Confession by accused while in police custody not be proved against him unless such confession has been made in the immediate presence of a Magistrate)

As per this Section, no confession made by any person while he is in the custody of a police officer shall be relevant or proved against him; however, a confession made by him, though in custody, but made in the immediate presence of a Magistrate is relevant.

Q.14 Injuries including bite marks are found on the body of the accused who is arrested in a case of femicide (killing a woman). The accused is sent in the company of two police constables to a doctor for medical examination. After leaving the accused in the consultation room of the doctor, the police constables go out for taking tea. When the doctor asks the accused as to how he sustained those injuries, the accused replies that they were inflicted by the woman who was murdered in the case. Is not the statement of accused hit by Section 26 of the Evidence Act ?

Ans. No. The statement of accused is not a confession but is only an admission. If, on the contrary, what the accused told the doctor was that the injuries on him were caused by the woman while he was strangulating her to death, then it would have been a confession which would attract the interdict under Section 26. (Vide State V. Ammini and Others-1987 (1) KLT 928 FB – S. Padmanabhan, K. T. Thomas, K. G. Balakrishnan - JJ) (This was the notorious Merlin murder case of N. Paravur. The verdict of the Full Bench of the Kerala High rendered by Justice K. T. Thomas Court was affirmed by the Supreme Court in Ammini v. State of Kerala (1998) 2 SCC 301 = AIR 1998 SC 260 – G. T. Nanavati, M. Jagannadha Rao - JJ ); N. Rajan V. State 1993 (2) KLJ 11 = 1994 Cri.L.J. 322 (DB) – M. M. Pareed Pillay, L. Manoharan - J. The mere fact that the constables had gone out for taking tea will not alter the nature of the custody of the accused. It is enough if at the time of making the confession the accused was under the ken of surveillance.

Q.15 Is confession made to Scientific Assistant while in the custody of the police but during the temporary disappearance of the police, liable to be eschewed from consideration ?

Ans. Yes. (Vide para 8 of Kishor Chand v. State of H.P (1991) 1 SCC 286 – P. B. Sawant, K. Ramaswamy - JJ; Para 57 of Ram Singh v. Sonia (2007) 3 SCC 1 = AIR 2007 SC 1218 – B. N. Agrawal, P. P. Naolekar - JJ).

Q.16 Should not the custody be formal custody of the police ?

Ans. No. It is enough if the accused is under some sort of surveillance or restriction. (Vide State of Andra Pradesh v. Gangula Satya Murthy (1997) 1 SCC 272 = AIR 1997 SC 1588 – A. S. Anand, K. T. Thomas - JJ).

The author is a former Judge, High Court of Kerala.