ICJ Decision: Yet Another Wake-Up Call for New Delhi

Dr. Aman M. Hingorani

17 July 2019 10:39 PM IST

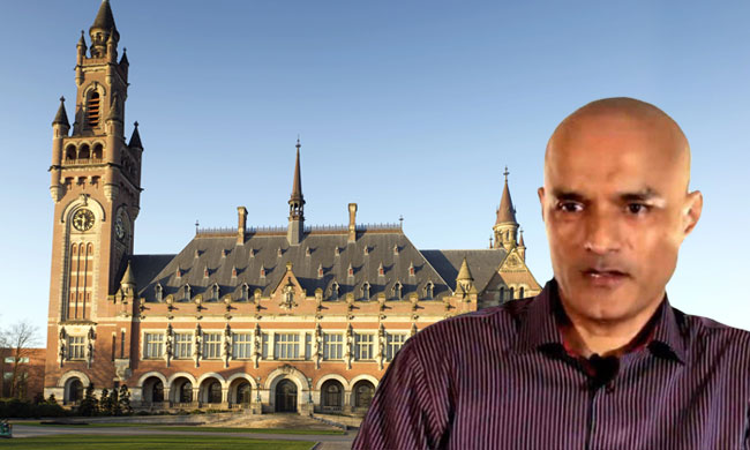

Today's ICJ decision in Kulbhushan Jhadav's case serves to remind us how crucial it is to take recourse (and timely recourse) to international adjudicatory mechanisms to decide international issues. It is against the backdrop of India's success at the ICJ that one must consider whether taking the Kashmir issue to the ICJ is a viable option for New Delhi. It is, in my opinion, the first step towards a resolution of the multi-layered Kashmir problem for the reasons given in my doctoral thesis way back in 2001 and in my book, Unravelling the Kashmir Knot (www.kashmirknot.com).

The way forward on the Kashmir issue must necessarily begin by undoing the mistakes committed in the past. As a point of departure, let us consider how we have reached where we are.

Declassified British archives establish that the partition of the Indian sub-continent was scripted by the British for their geo-strategic interests during their 'Great Game' (the precursor to the Cold War) with the then Soviet Russia, and to prevent Russian influence from travelling southwards towards the oil-rich Middle East. The British devised many strategies to contain the Russian influence. One strategy was to use Islam as an ideological boundary, as the territory along Turkey to China formed the Islamic crescent cradling Soviet Russia. North West Frontier Province and the Gilgit region of the princely state of Jammu & Kashmir ('J&K') formed part of this Islamic crescent. The British, knowing that they would have to transfer power into Indian hands and that the Government of independent India would not co-operate with them in their Great Game, decided to keep a 'slice of India' free from Indian control. And so, a friendly sovereign 'Pakistan' was necessary. The political agreement of partition driven by the British and the Muslim League, and eventually accepted by the Congress, was crystallized in British statutes - the Indian Independence Act of 1947, and the modified Government of India Act of 1935. The British provinces of Punjab and Bengal were to be partitioned according to the two-nation theory, which was conceived by the British and mouthed by their hand-picked M.A. Jinnah merely to justify the creation of Islamic Pakistan. The 560 odd princely states were given the choice to accede to either India or Pakistan or remain independent.

While planning the partition, the British had assumed that the strategically-located and Muslim-majority J&K would accede to Islamic Pakistan or at least be associated with it. However, J&K acceded to India on 26 October 1947 and became an integral part of the Indian Union. Such accession would have adversely impacted the Great Game for the British and defeated the very rationale of creating 'Pakistan'. That said, the British did not need the whole of J&K. They just needed the strategic Gilgit region for the Great Game, and the slice of land known as 'Pakistan-occupied-Kashmir' (or 'Azad Kashmir') as a buffer area to protect Pakistan from liquidation should India go to war with Pakistan.

Consequently, the British, in violation of every conceivable principle of international law, effected a coup of Gilgit on the night of 31 October 1947, to hand over such Indian territory to Pakistan. 'Pakistan-occupied-Kashmir' was captured by Pakistan-led tribals with the collusion of the British, whose officers headed both the Indian and Pakistani armies at the time.

India remained a British dominion till 1950, with the King of the United Kingdom as its formal head. Right up to 1948, New Delhi let Louis Mountbatten formulate India's Kashmir policy as chair of the Emergency Committee and the Defence Committee of the Indian Cabinet. Mountbatten has disclosed in an interview that, at the time of accession of J&K, he told Jawaharlal Nehru that he (as Governor-General) would sign the acceptance of the accession instrument only if New Delhi agreed to hold a plebiscite in J&K to determine the wishes of the people. New Delhi agreed to such plebiscite, having formulated the policy of ascertaining the wishes of the people in the case of disputed accessions, as of Junagadh and Hyderabad. New Delhi accordingly 'pledged' that it would regard the accession of J&K to be 'purely provisional' and subject to the wishes of the people who would 'settle' the question of accession.

Mountbatten went on to persuade New Delhi to involve the UNSC on the pretext of stopping the fighting in J&K, but with the purpose of taking the Kashmir issue out of India's domestic jurisdiction and to confer the international community (including Pakistan) standing with respect to J&K. The British strategy was to have the UNSC call for cease-fire without requiring Pakistan to first vacate the areas of J&K that it had occupied through aggression – which it did – and to have the UNSC look the other way when Pakistan consolidated its control over such occupied territory - which again it did. New Delhi was thus compelled by the UNSC to respect the ceasefire line and to helplessly watch Pakistan consolidate its control over the occupied territory. Thus, in the guise of the UNSC directed cease-fire, Pakistan (and through Pakistan, the British) got to retain precisely those areas of J&K that the British needed for the Great Game.

Mountbatten also succeeded in persuading New Delhi to commit before the UN a plebiscite in J&K under international auspices. The UNSC would then bypass India's complaint of aggression and hold India to its offer of plebiscite in J&K – which yet again it did. It was a trap laid at the UNSC by the British for New Delhi to confer a 'disputed territory' status on J&K, and New Delhi fell for it. India is the only country in history that has gone to the UN complaining of aggression against its territory and returned by committing to a plebiscite to first decide whether that territory even forms part of the country.

New Delhi meanwhile had realized the UNSC was being subverted by the political expediency of its members, but it was too late—the UNSC had tied India's hands and pre-empted it from recovering a substantial portion of the state. And so, New Delhi took the easy way out—it simply disowned the occupied territory of the state and its unfortunate people, who happen to be citizens of India under the Indian Constitution but continue to remain under foreign rule. New Delhi, following the policy of territorial status quo, even indicated its inclination to partition J&K along the lines recorded in the UN Yearbooks. New Delhi, therefore, went on to tell the UNSC on 15 February 1957 that it considered that it had 'a duty not to re-agitate matters' and had decided to 'let sleeping dogs lie so far as the actual state of affairs is concerned'. And so, when the Indian forces reclaimed part of the territory of J&K during the Indo-Pakistan wars, New Delhi actually handed back such territory to Pakistan. Again, when Pakistan cheekily gifted a part of the occupied territory to China in 1963, New Delhi confined itself to making formal, and impotent, protests.

New Delhi now decided that the UNSC had nothing to do with J&K. It somehow forgot that it was the one who had taken the Kashmir issue to the UN. Instead, it adopted the position that the Kashmir issue must be resolved bilaterally with Pakistan in terms of the Simla Agreement of 1972 and the Lahore Declaration of 1999. New Delhi jumps with joy at the slightest hint of any country endorsing the Kashmir issue to be a 'bilateral' one; it terms it as a major diplomatic victory. All of New Delhi's energies have been frittered away in seeking to check the internationalization of the Kashmir issue at considerable national cost, little realizing that each time it terms the Kashmir issue to be a bilateral one, it reiterates that Pakistan has a standing in the matter other than as an aggressor.

Notwithstanding the Parliamentary resolution to recover the occupied territories of J&K, New Delhi continues to emphasize the 'inviolability' of the LOC at every conceivable occasion and to strive, though unofficially, for the conversion of the LOC into the international border. It is content with boycotting China's Belt and Road Forum and lodging protests at the proposed formal annexation by Pakistan of the Gilgit region or at the use of such Indian territory for the China Pakistan Economic Corridor.

It is implicit in the policy of territorial status quo that New Delhi may cede national territory. New Delhi appears to have overlooked that it lacks competence under the Indian Constitution to do so. The Supreme Court had held in Berubari Union (1960) that Parliament could cede national territory. However, in Keshavananda Bharati (1973), the Court took the view that Parliament lacked power to tinker with the basic structure of the Constitution, which includes the unity and territorial integrity of the country. This position was reaffirmed by the Court in S.R. Bommai (1994) As a result, Parliament cannot give away Indian territory. New Delhi has, therefore, been barking up the wrong tree by following its policy of territorial status quo.

New Delhi today does not have a military, diplomatic, economic or political solution to comprehensively resolve the Kashmir issue. Rather, New Delhi's Kashmir policy has been to tighten New Delhi's grip on the part of the state with it by emasculating the state's autonomy guaranteed by Article 370 of the Constitution, and to hand over the Kashmir Valley to security forces to maintain law and order under the shield of draconian penal laws of dubious constitutional validity like the AFSPA, TADA and so on so forth. The security forces, who did not create the Kashmir issue and do not have a solution for it, have no option but to carry out the directives of their political masters to contain the violence that has now deteriorated to such extent that even school girls pelt stones at the security forces. It has evidently been forgotten that laws do not persuade just because they threaten.

And so, if New Delhi wants to seriously attempt to resolve the Kashmir issue, it must aim to change the current political discourse on this vexed problem, both internationally and nationally. Given India's past experience of the UNSC, one can understand the concerns of Indian observers at the prospects of taking the Kashmir issue to the ICJ. But then, the Kashmir problem is an international issue – it cannot but be one when a substantial part of J&K is occupied by two sovereign countries, Pakistan and China. New Delhi can keep harping about J&K being an integral part of India – the rest of the world simply does not agree. Moreover, New Delhi's Kashmir policy will not make Pakistan, or China, vacate the part of J&K occupied by them. The Kashmir issue, after all, is not merely the turmoil in the Valley (just about 9 % of J&K) and the problem of cross border terrorism. It includes the occupied territories of J&K and the forgotten Indian citizens residing there under foreign rule. New Delhi would, therefore, need to take concrete steps to break the political stalemate that has existed with Pakistan and China for decades.

With this background, let us now consider the reasons for taking the Kashmir issue to the ICJ.

It may be recalled that modern-day India and Pakistan are creations of the partition agreement of 3 June 1947, which was crystallized in the above-mentioned British statutes. However, as per these very statutes, all the princely states were to regain full sovereignty and such sovereignty vested in the ruler, regardless of the religious complexion of the people of the state concerned. It was the ruler alone who could decide to accede to India, Pakistan or remain independent. These British statutes were accepted by both India and Pakistan. Indeed, there is no doubt about the legitimacy of the states of India and Pakistan created by such statutes, and that such statutes comprised the constitutional law governing both India and Pakistan.

The sovereign ruler of J&K unconditionally acceded to India on 26 October 1947 in the manner prescribed under the constitutional law that created India and Pakistan and was accepted by India and Pakistan. As noted above, New Delhi viewed the accession as being 'purely provisional' and subject to the wishes of the people. By doing so, New Delhi overlooked that once a political decision (the partition agreement) had been crystallized into law (the British statutes), the executive (Government of India) created by that law cannot act contrary to the terms of that very law. It is well settled that a state cannot, by making promises, clothe itself with authority which is inconsistent with the constitution that gave it birth. The constitutional law creating modern day India mandated that it was only the sovereign ruler who could decide on the accession of his state to India. New Delhi had no power to lay down a contrary policy that the accession would be decided by the wishes of the people. Further, since the accession of J&K to India by its ruler was in terms of the same constitutional law that also created Pakistan, it would be fair to say that the law that gave birth to Pakistan itself made J&K a part of India. Moreover, it is not open in international law for a state (Pakistan) to challenge the accession made by a sovereign state (J&K) to another sovereign state (India), such accession being an Act of State. The ruler of J&K has never challenged the accession as being fraudulent or based on violence. Rather, the ruler acceded to India unconditionally in the three areas of external affairs, defence and communications and expressly retained his sovereignty qua the remaining matters. The UN, and every state 'contracting' with India (including Pakistan) are held in international law to have had the knowledge that New Delhi exceeded its powers under the said constitutional law by pledging to hold a plebiscite in J&K to settle the question of accession, and, that too, in the absence of its sovereign ruler. As a result, not only was New Delhi's 'pledge' of holding the plebiscite in J&K unconstitutional and not binding on India, the UNSC resolutions for holding the plebiscite were themselves without jurisdiction and in violation of the UN Charter as further explained in the book.

But then, it was New Delhi that had, in the first place, created doubts about the unconditional nature of the accession of J&K to India, internationalized the Kashmir issue and conferred a disputed territory status on J&K. It was New Delhi which consequently enabled the separatists, Pakistan and other countries to argue till date that it is a 'freedom struggle' that was underway in Kashmir. Therefore, it is New Delhi that needs, as a first step, to confirm, as it were, its title deeds to J&K so as to remove the 'disputed territory' tag on J&K. The only body in existence whose pronouncement will be considered as being authoritative and having legal effect on the international community is the principal judicial organ of the UN, namely, the ICJ. Since India is entitled in law to the entire territory of J&K, it lies in India's interest to have the ICJ examine the Kashmir issue. Such examination is not precluded by the Simla Agreement or any other bilateral agreement between India and Pakistan.

And so, New Delhi must at least now take recourse to the ICJ to depoliticize the Kashmir issue. While the Kashmir issue is certainly a political one, it is possible for New Delhi to separate the legal from the political aspect of the issue, so that it can vindicate its claim to the entire territory of J&K based on legal rights. If the ICJ gives a verdict in India's favour, and it is likely to do so in view of the legal principles formulated in the book, it will suffice to get rid of the 'disputed territory' tag on J&K. Further, the very presence of Pakistan and China in the territory of J&K would constitute 'aggression' under international law, and the international community would be under an obligation to put an end to that illegal situation as illustrated by the 1971 ICJ decision in Namibia. No country can then extend even 'moral' support to the supposed 'freedom struggle' in Kashmir. New Delhi must realize that it needs the international community to pressurize Pakistan to vacate its aggression and to stop cross-border terrorism. But for that to happen, New Delhi must first obtain a finding from the ICJ confirming the entire territory of J&K to be a part of India.

Further, in the unlikely event that the ICJ decides against India by opining that the future of J&K will be decided by the wishes of the people, New Delhi still stands to lose nothing. New Delhi has always maintained that the people of J&K have endorsed the accession of J&K to India, as is evident from the resolution of 15 February 1954 of the elected state Constituent Assembly. Indeed, the Assembly, which had been set up in 1951 by the sovereign ruler of J&K, framed the Constitution of Jammu & Kashmir of 1957 declaring J&K as an integral part of India.

It is true that law alone cannot resolve the Kashmir issue. And then there is the spectre of international politics as also of enforceability of ICJ decisions. However, a confirmation of the correct legal position by the ICJ will help alter the current political discourse, break the political stalemate between India, Pakistan and China, and swing political opinion in India's favour to create a momentum for winning the confidence of the people of the state. New Delhi must take further steps to regain the moral authority to be in J&K and to undo past mistakes as detailed in the book, its success being dependent on the character of the Indian State and of the men and women who run it.

Dr. Aman M. Hingorani is an Advocate on Record & Mediator at Supreme Court of India.

[The opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of LiveLaw and LiveLaw does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same]