A Tale Of Two Dissents

Kartikeya Sharma

29 Nov 2020 10:56 AM IST

When we think of dissents, we are reminded of the powerful words of the 11th Chief Justice of the United States Charles Evans Hughes that "a dissent in a court of last resort is an appeal to the brooding spirit of law, to the intelligence of a future day when a later decision may possibly correct the error into which the dissenting justice believes the court to have been betrayed."

While unanimity in a decision is desired to ensure consistency and finality, a dissent may reflect an independent application of mind and provide an alternate view to be considered by future judges and scholars. Constitutional courts engage with interpretation of laws and there is always more than one perspective to be considered during the process of interpretation. A dissenting opinion provides a contrary perspective as to what is the correct interpretation of the law as per the dissenting judge. A dissent may challenge the status quo and play an important role in changing the outlook of society towards contemporary issues.

Both the United States and India have seen their fair share of path breaking dissents and out of these opinions, a few have been affirmed as laying down the correct position of law. In memory of the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg of the Supreme Court of the United States, the dissent in Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.[1] must be mentioned as an example of a dissent that was affirmed by the Legislature by passing a bill to that effect. In this opinion, Justice Ginsburg held against the 180-day limitation period to bring forward a complaint regarding pay discrimination as it is not possible to determine pay discrimination within such a short time frame. This was incorporated into a legislation named the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act and it was in fact, the first piece of legislation signed by President Barack Obama in January 2009.

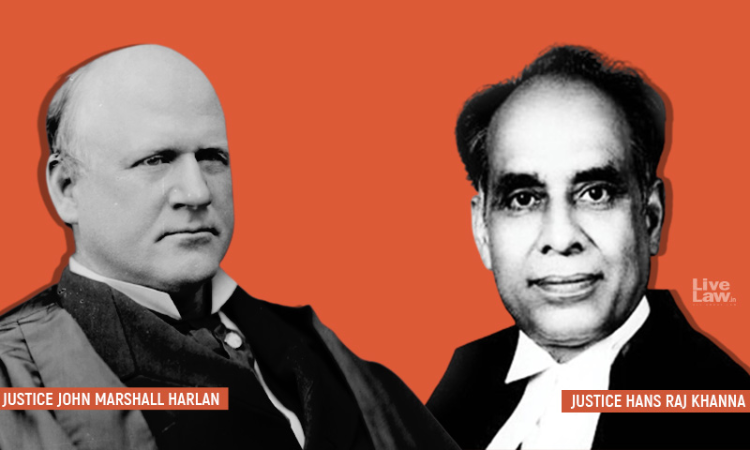

The focus herein is to discuss and highlight impact of two dissenting opinions penned by two great judges of the 19th and 20th century, respectively. The first being, Justice John Marshall Harlan's seminal dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson ("Plessy")[2] and the second, Justice Hans Raj Khanna's timeless dissent in A.D.M. Jabalpur v. Shivkant Shukla ("Jabalpur")[3]. These landmark dissents were delivered about 80 years apart and the circumstances surrounding them might have been completely different but, their impact was far reaching and are hailed as acts displaying moral fiber. A little context is required first to appreciate the brilliance of these dissents.

The background of the decision in Plessy was that Homer Plessy, a mixed-race man attempted to board a railway carriage in Louisiana earmarked for whites. What was interesting was that this was a deliberate attempt to test the segregation law in force in Louisiana and Homer Plessy wanted to be arrested in the white-only section of the carriage. When the case reached the Supreme Court of the United States, Plessy argued that 'separate but equal' was against the principles of legal equality but, this argument was rejected by the Court's majority. The majority held that while the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed equality, it was political equality which was protected which meant in the political sphere, people belonging to the colored race were on the same pedestal as whites. But this equality excluded social equality, as there was no comprehensible way the U.S. Constitution could equate an 'inferior' race to a superior one.

Justice Harlan, the lone dissenter, opined that in respect of civil rights common to all citizens, the Constitution of the United States does not permit any public authority to determine the race of those entitled to the enjoyment of their rights. Giving a broad interpretation to the Thirteenth Amendment which abolished slavery, Justice Harlan goes on to say that the amendment did not only abolish slavery, but also prevented the imposition of any burdens or disabilities that may be associated with the practice. Delving into an interpretation of the Louisiana segregation law, Justice Harlan held that that it was intended to keep the colored race separate from the whites and this would be an infringement of their personal liberty. This emerges from the law as it punishes railroad companies for permitting persons of the two races to occupy the same carriage and the State actively attempting in drawing a line between the two races regarding public conveyance. It must be noted here that Justice Harlan too was a man of his time like any other with all the failings and trappings of a white man in 19th century United States being a former slave-owner himself. His personal notions and bias find their way into the dissent when he states that the white race is dominant in terms of prestige, achievements, education, wealth and power and further, he believed that it would continue to be dominant if it remains true to its heritage whilst adhering to the principles of constitutional liberty. After this slight deviation, Justice Harlan comes back to the exposition of the law and Constitutional liberties. The famous words that followed deserve to be quoted verbatim, "But in view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer of the most powerful. The law regards man as man and takes no account of his surroundings or of his color when his civil rights as guaranteed by the supreme law of the land are involved."[4]

Justice Harlan concludes by predicting (correctly) that the majority opinion shall not stand the test of time just as the dreadful decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford[5]. The Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments were introduced to ensure universal civil freedom but, despite these changes to the law, there was no real equality before the law and that as a result of the majority opinion, States would be free to interfere with the enjoyment of rights, common to all citizens.

Coming to the judgment in Jabalpur, the setting of the case was bang in the middle of the infamous internal Emergency of 1975 which amplifies the impact of the dissent penned by Justice H.R. Khanna. The background of the case before the Supreme Court of India in a nutshell was that the Respondents therein had approached various High Courts challenging the validity of detention orders passed in furtherance of the Presidential Proclamation dated 27th June, 1975 under Article 359 of the Constitution which brought into effect the Emergency, supplemented by the Presidential Order of 8th January, 1976 whereby it was declared that the right to move any court for the enforcement of the rights conferred by Article 19 and the proceedings pending in any court for the enforcement of those rights shall remain suspended during the operation of the proclamation of Emergency. The case was decided by a majority of 4:1 with each of the judges on the bench writing their own opinions. The conclusion arrived at by the majority was that during a proclamation of Emergency, no writ of habeas corpus lay against detentions as Part III rights remained suspended at such a time. This in effect meant that the right to move a Constitutional Court for the enforcement of fundamental rights was taken away for the time being.

At the very outset of his dissent, Justice Khanna declares that vesting of the power of detention without trial in the hands of the Executive has the effect of combining the role of prosecutor and judge unto one body and is bound to reek of arbitrariness. The crux of his dissent lies in the finding that Article 21 is not the sole repository of the right to life and personal liberty as this right is the most precious right of human beings in civilized democratic societies. Article 21 does not bestow upon any individual the right to life and personal liberty, it is a mere recognition of the same and even in the absence of this provision, it would not be possible to say that this right does not exist. It is a manifestation of the rule of law and life and personal liberty are 'priceless possessions' of every individual in a civilized society. Justice Khanna also found that there can no curtailment of the right to seek a writ of habeas corpus from the High Courts under Article 226 during a proclamation of Emergency, observing that even during the wars of 1962, 1965 and 1971, the power of the High Courts to issue such writs was not curtailed.

Both these dissents now stand affirmed as having interpreted the law correctly. Justice Harlan's dissent upheld by the 1954 judgment in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka[6] and Justice Khanna's dissent by the 9-judge bench decision in Justice K.S.Puttaswamy v. Union of India[7]. What makes these dissents more influential is the context and the backdrop in which they were delivered. Justice Harlan, as mentioned above was a slaveowner himself and was a staunch supporter of the practice until the late 1860s after which he joined the Republican party and began opposing the abhorrent practice of slavery. Once he joined the Supreme Court in 1877, he wrote hard hitting dissents on civil rights' issues and the dissent in Plessy was his magnum opus and thereby cemented his legacy. A testament to the greatness of this opinion is the story that the legendary Thurgood Marshall, who later became the first African American justice on the Supreme Court, looked to this dissent for motivation and inspiration while arguing Brown v. Board of Education before the Supreme Court.

During the time of the judgment in Jabalpur, there was a sense of uneasiness and fear, especially within legal fraternity. After the 1973 judgment of Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala[8], the three senior most judges of the Supreme Court, Justices Shelat, Grover and Hegde were superseded by the Government and Justice A.N. Ray was appointed the 14th Chief Justice of India. In 1976, the Emergency was in full force and it could reasonably be expected that the Government would not hesitate to supersede any more judges. At the time of the decision, Justice H.R. Khanna was next in line to become the Chief Justice of India, and the stakes could not be higher. There was a widespread violation of civil rights, curtailment of press freedom and detentions without trial and the Supreme Court had the opportunity to uphold and protect democratic ideals and not bow down before the Executive of the day but, alas it failed in its Constitutional duty to protect the fundamental rights of the citizens. Justice Khanna, the lone and bold dissenter, paid the price for his opinion as he was superseded by Justice M.H. Beg for the post of Chief Justice, after which Justice Khanna gracefully resigned. The sacrifice made, as he was aware of the consequences of his dissent as noted in his autobiography Neither Roses Nor Thorns, ensured that Justice Khanna's name would be etched in our memories for a long time.

It is interesting to note a few similarities between the two justices. Justice Harlan, unlike most of his colleagues was not from an Ivy League law school but had a few advantages over his colleagues, first, he had a mixed race half-brother who was born into slavery and second, he had the advantage of serving in the Civil War as a soldier. The majority opinion in that case was authored by Justice Henry Brown who was a well to do man who did not participate in the civil war and was bereft of such advantages or first-hand experiences that may have been of assistance to him. Justice Harlan did not allow his personal biases or leanings come in the way of his steadfast interpretation of the Constitution and upholding the principles enshrined therein. Similarly, Fali Nariman in an interview opines that Justice Khanna may not have been as gifted intellectually as compared to some of his other colleagues like Justices Y.V. Chandrachud and P.N. Bhagwati but, what separated Justice Khanna from the rest was his unwavering and zealous commitment to upholding personal liberty regardless of the potential consequences flowing from his bold opinion.

The greatness of these two justices can also be measured by the tributes paid by none other than their colleagues on the bench in the decisions being discussed. Justice Henry Brown, author of the majority opinion in Plessy, at the end of his life noted that the brilliance of Justice Harlan's thinking was the assumption made by the latter in his dissent that the intent of the segregation law was to keep the colored race away and not vice versa, something which the 7 majority judges (including Justice Brown) seemed to have missed. The stand taken by Justice Khanna was accepted as the correct stance by Justice P.N. Bhagwati who publicly apologized in 2011 for siding with the majority in Jabalpur.

There is no doubt that dissent plays an important role in democracy and as we have seen from the examples of these two justices, dissents from the bench even serve the purpose of allowing posterity to correct historical wrongs. Civil rights or fundamental rights require constant protection and it is individuals like Justices Harlan and Khanna who stand vigil, guarding against attacks that have the ability to threaten and erode the pillars upon which the rule of law stands upright.