Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2016 Goes Against Constitutional Morality: Anupama Roy, Author And Expert On Citizenship Law

LiveLaw Research Team

15 Oct 2016 12:24 PM IST

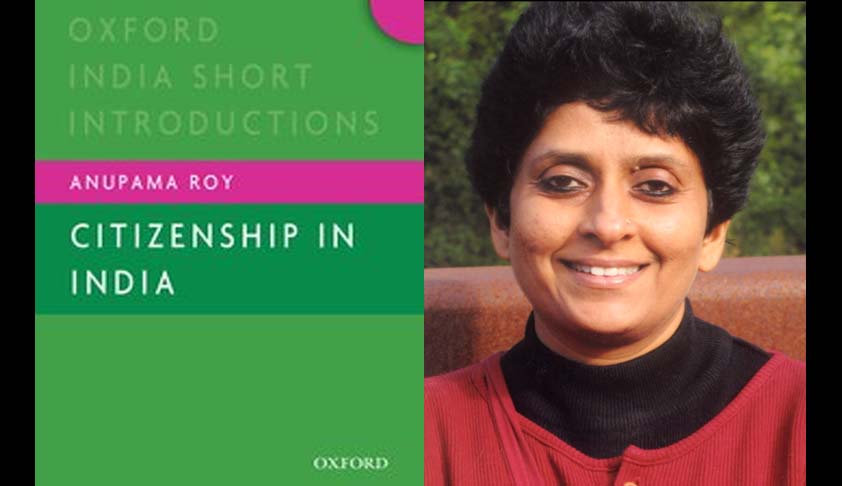

Anupama Roy is a Proessor at the Centre for Political Studies in Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Her research interests include legal studies, political anthropology of political institutions, political ideas, and gender studies. She obtained her Ph.D from the State University of New York at Binghamton, United States. She is the author of Gendered Citizenship: Historical and Conceptual Explorations (2013) and Mapping Citizenship in India (OUP, 2010), and has co-edited Poverty, Gender and Migration in South Asia (2008).

She is a respected academic and author on citizenship issues under the Indian Constitution. Her latest book, Citizenship in India, has just been released by the Oxford University Press, under its Short Introductions Series.

Livelaw interviewed her on some of the issues dealt in the book. In Part One, she shares her insights on the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2016, and the model adopted by the Constituent Assembly, while finalizing the provisions relating to citizenship in the Constitution. In Part Two, she answers questions on some of the contemporary issues.

Q.Your book on Citizenship has come at the right time, if one may say so. The Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2016 seeks to make drastic changes in the citizenship and immigration norms of the country by relaxing the requirements for Indian citizenship. Can you reflect on these changes being contemplated?

The Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2016, which is being considered by a Joint Parliamentary Committee, if passed, will be the sixth amendment to the Citizenship Act of India, 1955. The Bill may be seen as having an older pedigree, going back to the Citizenship (Amendment) Acts, 1986 and 2003. These amendments had set the grounds for prioritizing jus sanguini (blood and descent) over jus soli (soil or birth) by restricting citizenship by birth, and making descent/Indian origin the basis for the conferment of Overseas Citizenship of India to Persons of Indian Origin who were citizens of specified countries.

The proposed amendment is, however, unprecedented, in the sense that that never before has religion been specifically identified in the citizenship law as the ground for distinguishing between citizens and non-citizens.

In the recent past, orders given by the Supreme Court in two sets of public interest litigation questioning the constitutional validity of section 6A of the Citizenship Act, which pertains to citizenship in Assam and the question of foreigners and illegal migrants, have shown a similar trend.

The first of the two orders came in the context of a cluster of petitions filed by the NGOs Assam Sanmilita Mahasangha, Assam Public Works, and All Assam Ahom Association in the Supreme Court, challenging Section 6 A (3) and (4) of the Citizenship Act which provided that migrants from East Pakistan who entered Assam between January 1966 and March 1971 could become citizens of India.

While leaving the question of constitutional validity to be scrutinized by an appropriate bench, the judges traced the antecedents of the disputed section of the Act to the Assam Accord and confined their orders to giving directions to the central government and the government of Assam to buttress the eastern borders in line with the accord, streamline the process of deportation of illegal migrants, and expedite the preparation of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) for the state under the provisions of the Citizenship (Registration of Citizens and the Issue of National Identity Cards) Rules of 2003.

The second PIL by Swajan and Bimalangsu Roy Foundation, on the other hand, questioned that part of Section 6A of the Citizenship Act, which clubbed all immigrants who entered India after 24 March 1971 as illegal, and asked that they must be distinguished from ‘displaced persons’ (primarily Hindus and other minority groups fleeing persecution), who must be given legal status of citizens.

The petitioners asked that displaced persons should constitute a distinct category for legal protection, and that Hindus seeking shelter in Assam should be given citizenship on the same grounds that they have been given in Gujarat and Rajasthan between 2004 and 2007.

After the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) came to power in 2014, its leaders, including the BJP chief Amit Shah, spoke in rallies in Assam assuring citizenship to Hindus who had fled to India to escape religious persecution in Bangladesh. The government promised to enact a law for the rehabilitation of Hindu refugees from Pakistan and Bangladesh, setting up a task force to expedite pending citizenship requests from refugees. Indeed, the BJP declared immigration policy a major plank of its campaign in the Assam assembly elections in 2016.

Q: What are likely to be the consequences of these changes?

A: The present amendment by identifying Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhist, Jains, Parsis and Christians from Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan, as exceptions to the general law governing entry into India and the definition of foreigners and illegal migrants, and by making special provisions for their citizenship on the grounds of religious persecution, has introduced religion as a new principle into the citizenship law. Indeed by marking out Muslims as a residual category, it reiterates the narrative of partition, without, however, incorporating the principles of inclusion which were present in both the constitution of India and the Citizenship Act of 1955 at its inception.

While religious persecution is a reasonable principle for differentiation, it cannot be articulated in a manner that dilutes the republican and secular foundations of citizenship in India, and goes against constitutional morality.

Q. Indian Constitution guarantees certain fundamental rights to only citizens, for example, Articles 15, 16 and 19. What is the justification for this restriction and denial of similar rights to non-citizens?

A: In the Constituent Assembly, the fundamental rights were discussed in the Sub-Committee on Fundamental Rights which had three sittings from February to April 1947. There does not appear to have been a sustained debate on why the distinction between ‘person’ and ‘citizens’ was to be made in the enumeration of the rights to equality and freedom, and who would be the bearers of specific rights.

Much of the discussion on equality focused on a different set of distinctions: between the ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ figuration of rights and the nature of obligation they imposed on the state, rights which were justiciable and those which were ‘merely intended as guide and directing objectives to state policy’. Indeed, the points where the distinction between persons and citizens is discussed, are not many, and do not seem to have animated the members as much as questions of minority rights (in the right to equality), concerns around due process (in the right to life and personal liberty), and free speech (in the right to freedom).

It is in the context of the discussion on due process, however, that Alladi Krishnaswami Ayyar (Note on Fundamental Rights, 14 March 2016) brings up the distinction between the US Constitution and its protection of freedoms in the First Amendment, the equal protection guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment, and the ‘elastic interpretation’ of due process by the US Supreme Court.

For Ayyar, the question before the Constituent Assembly of India was whether to follow the model of the United States or of the later constitutions. The later constitutions differed from the US Constitution in that they merely referred to the right of citizens while providing for the law of citizenship. The US Constitution on the other hand, guaranteed certain human rights to all people for the time ‘resident in or under the protection of the United States’.

Whereas certain rights were secured only to citizens (e.g., fifteenth and nineteenth amendments pertaining to franchise), most of the rights secured by the first eight amendments, including the fifth amendment, giving protection to life liberty and property, were shared by all persons in the United States. (Shiva Rao, Vol II, p.68).

Q: Which model the Constituent Assembly adopted then?

A: It may be said that the Constituent Assembly followed the inclusive model of the United States, by not limiting all fundamental rights to citizens, but only those which required a relationship of obligation between citizens and the state, as K. T. Shah was to note in his submission of 23 December 1946. Shah would argue that over the past 200 years ‘civil rights’ had become standardized and were incorporated in varying terms in the constitutions of the leading countries of the world.

These rights were founded on the conception of justice between man and man, and could not be secured without equality in the social system and before the courts of law. The most important of these rights to Shah were the rights to the liberty of persons and to privacy, which were, however, not confined to citizens but were the rights of ‘humanity in general’. The right to life, therefore, so far as mere sanctity of life was concerned would apply to both ‘citizens and strangers’.

But as far as the conditions enabling persons to enjoy the ‘fullness of life’ and opportunities for self-expression and self-realization’ were concerned, they required provision of facilities (education, health, entertainment etc.), which in turn required an outlay, the wherewithal (e.g. through taxes) of which would come from citizens. These rights will, therefore be for citizens and strangers, but preferentially for citizens.

On the other hand, for Shah, political rights, required a different kind of obligation, so that ‘While the general level of civilization and the amenities of life provided there under would be common to citizens and strangers, certain rights of citizens which become the obligation of the state are necessarily confined or at least primarily belong to the citizen (Shivarao, Vol. II, p.43).

(to be continued in Part Two)

This article has been made possible because of financial support from Independent and Public-Spirited Media Foundation.