1973 April 26- The Saddest Day In The History Of Our Free Institution

Amit A. Pai

26 April 2023 6:22 AM

This was the title to a Joint Statement issued by eminent members of the Bar and former members of the Bench.[2] On 26th April 1973—half a century ago today—is the only day in the history of the Supreme Court that the Bar struck and called the action of the Government "a blatant and outrageous attempt at undermining the independence and impartiality of the judiciary."[3]. It was the day...

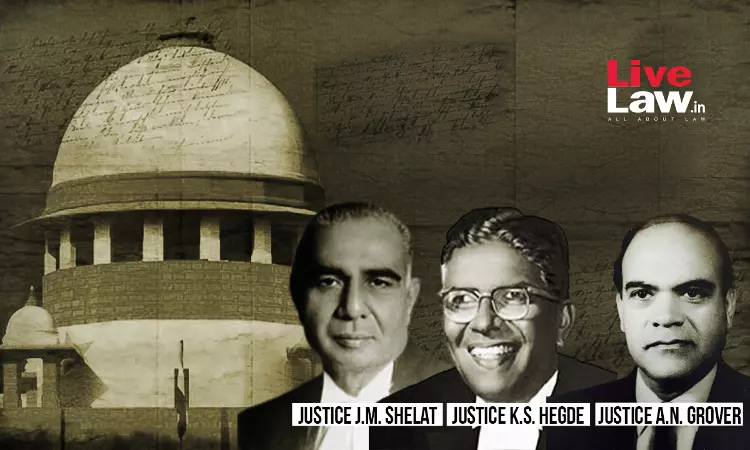

This was the title to a Joint Statement issued by eminent members of the Bar and former members of the Bench.[2] On 26th April 1973—half a century ago today—is the only day in the history of the Supreme Court that the Bar struck and called the action of the Government "a blatant and outrageous attempt at undermining the independence and impartiality of the judiciary."[3]. It was the day Chief Justice A.N. Ray took over as Chief Justice of India—superseding three senior Justices. The outrage was fueled by the fact that unlike the twelve previous Chief Justices, who had been appointed by the constitutional convention of seniority, Justice Ray superseded Justice J.M. Shelat, Justice K.S. Hegde and Justice A.N. Grover—the three Judges, who were a part of the majority in Kesavananda Bharati. Obviously, the Government has done this smarting under the majority decision in the Kesavananda Bharati case, decided a day before the announcement. And that prompted the Joint Statement: “(i)t cannot be denied that the three Judges were passed over only because of their rulings displeased the Government.”

Defending this affront to the cherished principle of independence of the judiciary, Minister Kumaramangalam[4] would say in Parliament,

“Certainly, we as a Government have a duty to take the philosophy and outlook of the Judge in coming to the conclusion whether he should or he should not lead the Supreme Court at this time. It is our duty in the Government honestly and fairly to come to the conclusion whether a particular person is fit to be appointed the Chief Justice of the Court because of his outlook, because of his philosophy as expressed in his…opinions, whether he is more suitable or a more competent Judge….We do not want any committed judges. No judge has to commit himself. But we do want judges who are able to understand what is happening in our country; the wind of change that is going across our country; who is able to recognize that Parliament is sovereign….We are entitled surely to look at the philosophy of a judge. We are entitled to look into his outlook. We are entitled to come to the conclusion that the philosophy of this judge is forward-looking or backward-looking and to decide that we take the forward-looking Judge and not the backward-looking Judge.”

The Kumaramangalam doctrine, as it was known, argued that the Executive had the prerogative to appoint Judges who are in tune with their own philosophy. Indeed, the Government unabashedly wanted a “committed judiciary”. In response to this, Nani Palkhivala, in his book Our Constitution Defaced and Defiled, aptly said:

“A committed judge is a contradiction in terms. You cannot have a committed judge any more than you can have boiling ice cream. Either a man is committed or he is a judge in the true sense; he cannot be both….”[5]

At a dinner honouring the retiring Chief Justice Sikri on 25th April 1973, Justice Sikri said to an embarrassed Justice Ray, “You will rue the day you accepted the Chief Justiceship.”[6] The appointment of Chief Justice Ray in supersession of Justices Shelat, Hegde and Grover, who resigned in protest, was just the beginning of the assault on the judiciary’s independence.

During the Emergency, transfer orders were made to create a sense of fear amongst the Judges who were perceived to be unfavourable to the Government. In early 1976, the Government refused to continue Additional Judge Justice U.R. Lalit of the Bombay High Court and Justice R.N. Aggarwal of the Delhi High Court. Similarly were Justice D.N. Chandrashekar, Justice M. Sadanandaswamy of the Karnataka High Court, and Justice A.P. Sen[7] of the Madhya Pradesh High Court. Justice Rangarajan[8] was transferred from the Delhi High Court to the Gauhati High Court. Justice S.H. Sheth of the Gujarat High Court challenged his transfer and highlighted the issue of punitive transfer in an era of censorship. Justice P.M. Mukhi of the Bombay High Court sought to be transferred to the Calcutta High Court, but a heart attack suffered by the popular Judge caused the Government to backtrack. He soon died. The most grievous blow of them all was the supersession of Justice H.R. Khanna after his landmark dissent in A.D.M., Jabalpur. With a sense of stoicism, Justice H.R. Khanna recorded that when he prepared his dissent, he knew it was “going to cost me the Chief Justiceship of India.”[9]

Sad was the day when the Executive trampled upon the judicial independence. Sad is going to be the day whenever, in any corner of the world, this executive overreach recurs. So this piece is to commemorate the supersession of Justices Shelat, Hegde and Grover half a century ago and serve as a caution for the days to come. It is imperative to remember the wise words attributed to George Santayana – “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Will history repeat itself? Or worse still, it is already repeating itself?

Recently, the Executive has frontally attacked the Collegium System for the appointment of Judges. Time and again, votaries of the Executive have asserted that the appointment of Judges is an exclusively Executive function, and the Collegium System, not being founded in the text of the Constitution, is alien to our polity. The Government has asserted that it has the right to appoint Judges to the Constitution Courts, notwithstanding the judgments of the Court – where “consultation” with the Chief Justice has been read to mean “concurrence”. The Court is often accused of usurpation of that power that was reserved for the Executive. But seldom does one remember that this so-called "usurpation" of the power to appoint Judges was not the natural choice for the Court. In S.P. Gupta, the Court did yield to the power of the Executive. It was not until 1993. Wiser with the experience of the previous decade, the Court read the independence of the judiciary with the power of appointment sourced in Article 124 to manifest the Collegium System. It remained seriously unchallenged till 2013 when the Government of the day sought to replace the existing system with the NJAC by the 99th Amendment to the Constitution. Upon a basic structure review, the Constitution Bench found the NJAC to fall foul of the cherished principle of an independent judiciary. Clearly, smarting from the striking down of the NJAC and the Court's closing the backdoor on the MoP, the Government has selectively appointed Judges recommended by the Collegium—arbitrarily delaying appointments and whimsically altering seniority. Some of the Government’s objections to some recommendations—which are thankfully now available because of the detailed reiteration by the Collegium –smack of the Kumaramangalam doctrine. The alteration of the seniority and 'pick and choose' policy adopted in the appointments is characteristically similar to the supersessions, which began fifty years ago today.

Perhaps, the Collegium, too, has faulted in not asserting its power and role envisaged under the Constitutional scheme and even in recalling some of its recommendations in view of non-acceptance or delay in implementation by the Government. The Governmental disdain for the recommendations made by the Collegium is not only an insult to judicial independence but also to the rule of law and, thus, the backbone of the Constitution. The unfortunate perception that those who displease the Government by their views or actions do not pass the muster is looming large—a perception that echoes the Joint Statement issued on 26th April 1973. In Hamilton’s words, “The complete independence of the courts of justice is peculiarly essential in a limited Constitution.”[10]

The judiciary is the last bastion of constitutional democracy; it stands between the people and the despot, as recent events in Israel bear a testimony. And for this reason, Babasaheb Ambedkar was prompted to term the power of judicial review enshrined in Article 32 as the very “soul of the Constitution”. Although the Collegium System most certainly has its drawbacks—criticisms ranging from being the best-kept secret in the World in view of its lack of transparency to nepotism and favouritism—it is perhaps the best system for our complex polity. The words of the retiring Chief Justice Sikri to the incoming Chief Justice Ray could not have been truer. But what is even truer is the undermining of the judiciary's independence and the Collegium's power, as was done half a century ago. For We, the people, will rue that day if the last bastion were to fall. The saddest day in the history of our free institution ought to never come again.

M.C. Setalvad, M.C. Chagla, J.C. Shah, K.T. Desai, V.M. Tarkunde, N.A. Palkhivala. As published in N.A. Palkhivala Ed., A Judiciary Made to Measure. ↑

Granville Austin, Working a Democratic Constitution: A History of the Indian Experience, Oxford University Press, 2014 Reprint, Page 285 ↑

According to Justice P. Jaganmohan Reddy, the supersession was planned before the Kesavananda Bharati judgment. He says that at a reception a week before the judgment, Mohan Kumaramangalam shook hands with Justice Ray and "Congratulation next week", to which Justice Ray responded with a grateful nod. See P. Jaganmohan Reddy, The Judiciary I Served, Orient Longman, 1999 Ed., Page 242-243. ↑

N.A. Palkhivala, Our Constitution Defaced and Defiled, MacMillan, January 1975 Ed., Page 103 ↑

See P. Jaganmohan Reddy, The Judiciary I Served, Orient Longman, 1999 Ed., Page 245. ↑

He was one of the Judges who heard Shiv Kant Shukla’s habeas corpus plea. ↑

He was one of the Judges who heard Kuldip Nayyar’s habeas corpus plea. His wife was so worried that she requested in not to take a morning stroll because he may be accidentally run over. See Granville Austin, Working a Democratic Constitution: A History of the Indian Experience, Oxford University Press, 2014 Reprint, Page 344 – 347. ↑

H.R. Khanna, Neither Roses nor Thorns, E.B.C., 2018 Reprint, Page 86 ↑

Federalist Paper No. 78 ↑

Author is Advocate on Record, Supreme Court of India.

Views Are Personal