The New Bills On Criminal Law Bring More Dissapointment Than Hope

Anant Prakash Mishra & Samayra Adlakha

18 Aug 2023 3:00 PM IST

When the constituent assembly finished drafting our Constitution, a new dawn awaited the people of India. It was a moment of proud metamorphosis that needed a realization that the words “We the people” have started to resonate with the citizens who no longer were the subjects of their colonial masters. The words in the opening quote were meant to warrant caution and were orated by K Hanumanthiah in the Constituent Assembly. He graced the assembly as one of the founding fathers and was among the members who were not particularly exultant with the magnanimous draft of our constitution.

In the seventy-five years of India’s independent history, the Constitution has undergone siege multiple times and has faced attempts to defile, submerge, and outright bending of it. The years of the emergency and Mrs. Indira Gandhi’s tryst with political power are glaring examples of the same. Constitutional Historians have poured volumes of ink on the subject but there is a reason why our Constitution has survived every attack and has lived to fight another day. The answer is that the people of this country have always deferred to the wisdom of the founding fathers of our constitution.

The Government of India Act, 1935 formed the chassis of our constitution and the assembly borrowed a significant portion from various constitutions of the world. Borrowing per se, does not imply that the Constitution did not live up to the expectations of the people. On the contrary, it commands a solid reverence from the masses and is a remarkable work of drafting. Yet sometimes, our constitution appears less indigenous and more foreign. Similar is the case with almost all the other laws of the country, particularly the criminal laws. It has often been pointed out that the Penal code, Criminal Procedure and the law on Evidence still reek of the British administration and lack the Indian experience. Reforms in the domain of the criminal justice system have been past due and getting rid of our colonial antecedents remains a prudent choice.

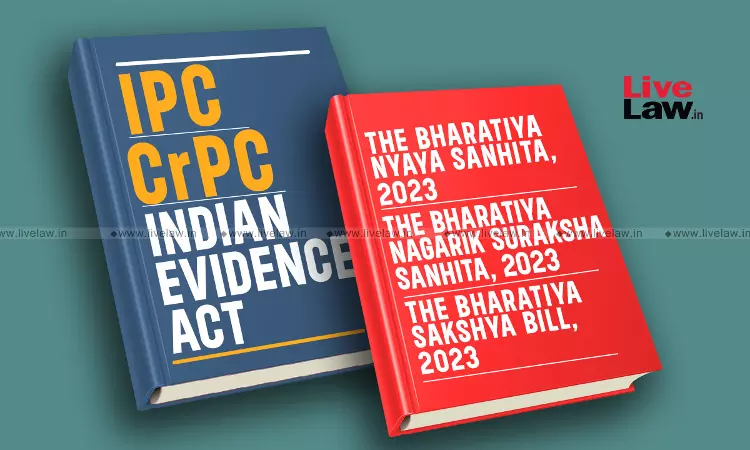

The current monsoon session of the Parliament saw the Union Home Minister introducing three bills to replace the previous existing codes on criminal law. The Indian Penal Code, 1860 is set to be replaced by BhartiyaNyaya Sanhita, 2023. The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 is to be replaced by The BhartiyaNagrik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 and the Evidence Act, 1872 will be taken over by TheBhartiya Sakshya Bill, 2023.

What has changed? Is it a transition worth applauding?

The three bills that propose to alter the existing scheme of things have been sent to a parliamentary standing committee. While to the average voter, the introduction of these bills might appear as an act of renunciation of the British ink in our laws; on a meticulous analysis of the same, it appears that the bill is more pomp than tangible progress.

The Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita has undergone certain additions, deletions as well as omissions but the material scheme of the things have remained the same. Claims were made in the lower house of the parliament stating that the law on sedition has been repealed. Although factually the same stands correct but in the new bill it has found a place under a new clause. Chapter seven of the new bill deals with the offences against the state. Clause150 that falls in the said chapter covers the acts that endanger the sovereignty, unity and integrity of India. The language used is sufficiently vague with little to no clarity as to what will constitute as ‘subversive activities’, ‘encourages feelings of separatist activities’ or the acts that will endanger the unity and integrity of our republic. Vagueness gives rise to discretion and when those in power are handed with unfettered discretion it usually clamps on dissent. The old law on sedition had no definitional clarity and the same remained a cause of concern. State of affairs went sordid to a point when a bench led by the then Chief Justice NV Ramana had to put the law on abeyance.

To be precise, it is not being argued that the acts that ‘actually’ harm the integrity of our nation should go unpunished or a separationist/terror outfit should not face the action of law. On the contrary, the contours of the said law should be clearly laid down in order to leave a reduced scope for discretion of the government.

The Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita has also retained the old penal code approach on the laws relating to obscene materials, decency and morality. The dated Victorian-era moral code of Lord Macaulay stills finds a place in our Nyaya Sanhita. The government can pat their back and call the bill progressive but it falls short of recognising the offence of rape on a married woman by her own husband.

A genuine attempt at revamping the criminal manual cannot take place in isolation of courtroom discourse and judicial pronouncements. In JosephShine, recognising the law of adultery as perpetuating a deeply entrenched patriarchal order by considering the husband as the owner of a woman’s sexuality, the Supreme Court struck down Section497 of IPC. However, a provision criminalising the “enticing” or “taking away” of a married woman from “that man” or anyone “having the care of her on behalf of that man” having similar paternalistic underpinnings continues to exist in the proposed Nyaya Sanhita. This finds mention in Clause 83 of the Sanhita and which is similar to Section 498 of the Indian Penal Code.

Furthermore, the current regime seems to have misconstrued the Navtej Johar judgment which read down Section377 of IPC to decriminalise consensual sex between adults including same sex individuals. The parts of the provision relating to non-consensual sex as well as bestiality were upheld. However, the Nyaya Sanhita bill has completely repealed the provision which protected adult men from sexual assault. The question of inclusivity remains unattended in the Sanhita as the provision on rape is strictly limited to a woman and does not include a transgender woman or others that may be aggrieved by acts of such nature. The Transgender Persons Act, 2019 recognises only ‘sexual abuse’ for which the maximum punishment is two years. Thus, the law on rape could have been reworked to go beyond the concept of ‘biological woman’.

The Bhartiya Nagrik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 under the proposed Clause172 seeks to make it mandatory to conform to the directions of the police. Sub-Clause (2) gives power to the police to remove or detain a person and release them when the occasion is past. While it is essential to maintain law and order but increasing police powers may not be the best course of action in this regard. Police brutality and abuse of power do not remain unheard of in this nation. To attain true independence for the citizenry, the government must overcome the mindset of ‘Control’ as the same remains a quintessential precursor in a democracy.

There can be no denial of the fact that laws during the British Raj were enacted to keep us i.e. the subjects in line. Therefore, it is imperative that we change our outlook and grow out of the colonial lens on law and order in India. Today, we are drafting the law for our citizens and in doing so the balance must tilt heavily towards ‘Justice’ than ‘Governing and Regulating’. It is not everyday that major bills that seek to replace a regime more than a century old are tabled in the Parliament. This should be seen as an opportunity to make history wherein a lot could have been remedied in the criminal justice system. The exercise would be a futile attempt if change in section/clause numbers of the existing codes is the only major outcome of the process. A thorough and nationwide stakeholder consultation must be carried out so that the public could contribute meaningfully and we can collectively row towards tangible change. If the contemporary acts are to be repealed in toto the aftermath of the exercise should be justifiable; otherwise small alterations can be carried out via amendments. As much as a change is required and desirable, merely adding the word ‘Bhartiya’ to the title of the bills will not by itself drag our laws out of the imperial shadow.

Anant Prakash Mishra is a lawyer and Samayra Adlakha is a student at The NALSAR University of Law, Hyderabad. Views are personal.