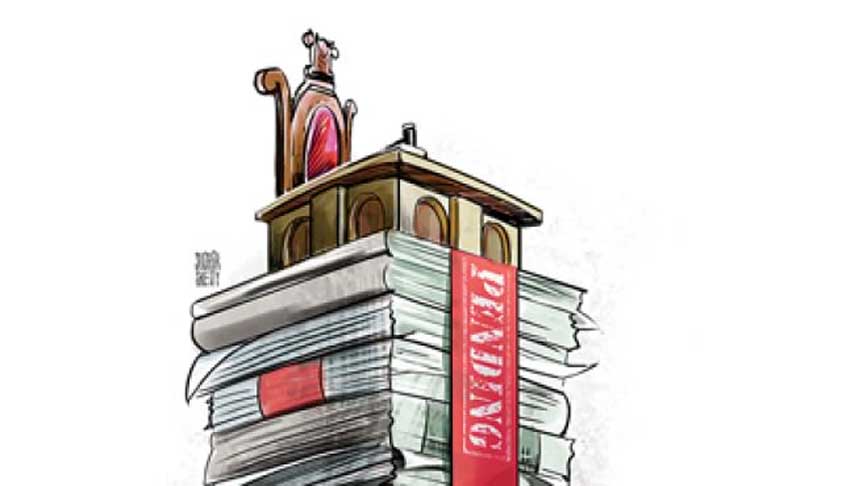

‘See You In Court’ Or ‘See You Out Of Court’? A Burdened Judicial System - Can ADR System Be An Answer? (Part I)

Richa Kachhwaha

21 April 2017 7:07 PM IST

A well-functioning court system is regarded as an institutional requisite for not just robust economic growth, but also for human well-being [On the need for efficient courts to promote well-being, wealth, and justice in India, see Justice Without Delay: Recommendations for legal and Institutional Reforms in Indian Courts, Jindal Global Legal Research Paper No. 4/2011]. Both law and development theorists are of the view that the socio-economic development of a country increases its reliance on formal institutions. Litigants approach courts for redressal of their grievances and to protect their rights which are guaranteed by the law. The justice system is expected to deliver speedy and affordable justice shorn of the complexities of procedure. The quantity and quality of justice delivered is, however, to be balanced. If justice is not delivered in a manner that advances the rule of law and upholds social values in the society, the consequences can be catastrophic. The core principles of fairness, equality and judiciousness cannot be sacrificed at the altar of speedy/expeditious disposal. While “justice delayed is justice denied”, it must not be hurriedly imparted either.

Growing economic prosperity is often accompanied by an increase in civil/commercial litigation The connection between the two is attributed to the fact that higher prosperity is the result of an increase in diverse business activities and urbanization, which in turn gives rise to civil/commercial disputes. There also exists a direct connection between the effectiveness of a country’s judicial system and the investor confidence by guaranteeing the security of property rights and the enforcement of contracts. The World Development Report of 2002 [World Bank. 2002: World Development Report 2002: Building Institutions for Markets. New York: Oxford University Press. © World Bank] talks about how the absence of formal contract enforcement mechanisms limits the expansion of trade. Professor Marc Galanter, a noted Fulbright scholar and a Fellow of the American Institute of Indian Studies, in his work titled Afterword: Explaining Litigation [9 Law & Society Review 347 (1975)] famously noted that economic growth, manifests itself in more businesses and more governmental activity and, presumably, greater litigation activity by those entities.

The fact that there are many issues which have crippled India’s justice delivery system is well-known. Over the years, several studies on the subject have been conducted and data routinely compiled and analyzed. What gets overshadowed in the process is that although pendency of cases is mounting, so are the numbers of annual filing and disposals. Even with the current strength in the judiciary, courts dispose of almost as many cases as are filed in a given year. For instance, between July 2014 and July 2015, with a working strength of between 15,500 and 15,600 judges, the subordinate courts disposed of 18,730,046 cases as against 18,625,038 cases which were filed in the same period - a little more than the number of cases filed.

As per the data released by the Ministry of Law and Justice in March 2016, the Supreme Court is disposing pending cases at a faster rate. Despite pendency of cases before the apex court, the court’s efforts to dispose these cases are showing results. In particular, the figures for the period 2013-16 reveal that pendency in the apex court has come down from 66,603 cases to 59,468 cases.

A somewhat similar trend, although not entirely consistent, is seen in the total number of cases pending with the 24 high courts - pendency of 45,89,920 cases as of September 2013 contrasted with 40,05,704 cases as of July 2015.

Although fast track courts have received flak for their performance, out of 36 lakh cases transferred to the fast track courts since their inception, close to 30.7 lakh have been disposed. In effect, fast track courts have succeeded in disposing of more than 80 per cent of cases transferred to them.

Despite the broad statistics of the performance of the judiciary, the faith in the Indian judicial system endures. A scientific, rational and objective analysis about why the backlog has accumulated and whether with a specific strategy the same can be cleared is now underway. Some of the other factors that compound the problem of pendency and delay in courts, but are not adequately highlighted, include the increasing number of state and central legislations; continuation of ordinary civil jurisdiction in some high courts, appeals against orders of quasi-judicial forums reaching high courts, number of revisions/ appeals, indiscriminate use of writ jurisdiction, lack of mechanism to monitor, track and bunch cases for hearing, etc. In 2016 ‘vacancy in courts’ and ‘pendency of cases’ clearly captured the nation’s imagination like never before. Emotional outbursts from the higher Judiciary and the push for judicial reforms as the top priority of the Centre have re-scripted the narrative surrounding the challenges facing the judiciary.

Pendency and Backlog

According to a recent note prepared by the Ministry of Commerce, commercial lawsuits between businesses in the Indian courts are among the lengthiest, costly and complex cases. It takes 1,420 days to enforce a contract in India and costs nearly 39.6 per cent of the claim value because of the long gestation period from filing of the suit to final judgment.

“The trial and judgment in India almost takes about 1095 days and enforcement of the judgment takes 305 days. A high cost of engaging lawyers and other court costs increase the burden on businesses,” the ministerial note said.

In particular, India’s lower judiciary is regarded as “dysfunctional”- for a case in any subordinate court of the country, the average time taken for a decision to be made is 2,184 days, nearly six years! There is now some evidence that the backlog could be discouraging use of the courts. Not surprisingly, pendency of cases in district courts across the country continues to be abnormally high at 2.8 crore (as of September 30, 2016).

Statistics show that in the period between July 1, 2015, and June 30, 2016, district courts across the country grappled with a backlog of 2,81,25,066 civil and criminal cases. Although a large number of matters, 1,89,04,222, were also disposed off during this period.

The Chief Justices’ Conference of 2015 had resolved that each high court will establish an arrears committee to clear the backlog of cases pending for more than five years. The implementation and efficacy of this move is yet to be seen. Valuable suggestions have also been made on various occasions by the members of the higher judiciary to tackle the issue. Notably, former Justice AP Shah, Chairperson of the Law Commission of India, rightly opined that routine matters like traffic and police challans account for over one-third of all cases pending in the lower courts and that such cases should be removed from the regular court system altogether, and instead resolved by other mediums like evening courts.

This could be done with all petty matters involving small criminal cases so that the courts are left to deal with only criminal offences of a serious nature, thereby helping to reduce backlog and delays.

On another note, in 2014, former CJI Justice Lodha proposed to make judiciary work throughout the year and do away with the present system of having long vacations, especially in the higher courts. The proposal, however, did not entail any increase in the number of working days or working hours for the judges, it only meant the judges would go on vacation at different times of the year.

Number of Judges: To increase or not to increase?

It is not just slow disposal of cases by the courts/ judges which has contributed to the backlog, there is also the issue of judicial vacancies - an issue which is now in the spotlight. Data released by National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) shows that with the present strength of judicial officers in district courts, trial in only approximately 13 per cent cases was completed under the Indian Penal Code during any given year.

Reportedly, India has approximately 17 judges for a million of the population, with nearly 5,000 posts of judicial officers being vacant, when the sanctioned strength of judicial officers is 21,324. The figures as on July 2016, as seen from the National Judicial Data Grid and Department of Justice data, reveal that there are 16,438 judges at the subordinate judiciary level, 621 in high courts, and 29 in the Supreme Court.

Given the “alarming situation” surrounding judicial vacancies, the apex court has come out with suggestions as well as sharp remarks in two recent reports — Indian Judiciary Annual Report 2015-2016 and Subordinate Courts of India: A Report on Access to Justice 2016.

These reports have called for increasing the judicial manpower “manifold” — at least seven times — to overcome the crisis by appointing approximately 15,000 more judges in the next three years to tide over the current critical situation.

Highlighting the importance of judiciary and timely delivery of justice, the reports have also said “overworked judges, overburdened court staff, chronic shortage of court-space and unending wait to justice does not complement the policies of the State”.

Former Chief Justice of India TS Thakur’s now famous outburst in April last year about the “burden” on the judiciary and the insufficient judicial strength as the main reason thereof has brought the spotlight on the question of the number of judges which the country needs.

While the former CJI quantified this insufficiency with a claim that India needs a staggering 70,000 judges to clear the backlog, experts and Law Commission think otherwise. Based on a fixed time frame for disposal of a case of three years (a hypothetical outer limit), the number of judges needed to clear the existing backlog can be assessed, irrespective of when the cases were filed.

This methodology was adopted by the Law Commission of India in its 245th report Arrears and backlog: Creating additional judicial (wo)man power dated July 2014.

This is also how governments and the judiciary assess judge strength on a regular basis. After all, disposal of a case is not a mechanical task; hearings have to take place, evidence has to be presented; and then the judge has to apply his/her mind to arrive at a decision.

Legal experts also point out that appointment of judges is merely one part of the problem. The country’s judicial system is in the need of an extensive overhaul - from increasing the strength of court staff and creating (as well as modernizing) judicial infrastructure to introducing more efficient (electronic) systems for the judges to track and manage the cases. In effect, the backlog and delay can be very well tackled if the courts had the necessary tools to function more efficiently (read as better infrastructure and support).

Interestingly, many judicial appointments have been held up due to the standoff between the Supreme Court collegium and the government over the finalization of the procedure for the selection process of judges.The appointments have been held up following a standoff between the apex court collegium and the government over the finalization of the memorandum of procedure for selection of judges. Notably, judiciary was at loggerheads with the executive and legislature during 2014-15 on the National Judicial Accountability Commission Act (NJAC), which sought to expand the role of executive in judicial appointments and make them more transparent. Ultimately, in October 2015, the Supreme Court struck down NJAC citing the need for absolute judicial independence. The judgment was met with some cynicism on the ground that it is “morally indefensible” that only the judicial fraternity can make higher judicial appointments and the other Constitutional organs are not allowed to have any say in the matter. Critics, however, say that the government should have no role in selecting judges and the new panel could lead to politicization of appointments. The NJAC debate brought in the open the longstanding (albeit non-vocal) concerns that even judicial appointments are not above suspicion! But the NJAC crisis had a silver lining. While it rejected the NJAC, the Supreme Court did acknowledge the flaws in the current appointment system and tasked the government to gather public feedback for improvement in the process.

Courtrooms

Quality and adequate judicial infrastructure in the country is lacking. It is lamentable that judges, particularly in the lower courts, still lack basic facilities to perform their work. There have been instances where a number of judicial officers posted at a place could not function for want of courtrooms. Also, conversely at other places, vis-à-vis number of judicial officers posted, the number of pending matters was negligible. In the absence of necessary statistics, less number of courtrooms have been constructed in districts where number of pending matters were very high. Non-availability of adequate number of courtrooms has quite obviously resulted in hampering smooth delivery of justice. The National Mission for Justice Delivery and Legal Reforms, in one of its reports, pointed out that “adequacy of judicial infrastructure is a pre-requisite for reduction of pendency and backlog of cases in courts”. The report hit the nail on the head. Set up in 2011 by the Department of Justice, the mission was tasked with the twin objectives of “increasing access by reducing delays and arrears; and enhancing accountability through structural changes and by setting performance standards and capacities”.

As of 2016, the subordinate judiciary is working under severe deficiency of 5,018 court rooms. The existing 15,540 court halls are not enough to cater to the sanctioned strength of 20,558 Judicial Officers as on 31 December, 2015, resulting in the judicial officers having to work under undesirable conditions.

More clarity on how many additional courts are required for each year for the next few years is required, especially if the burden on the courts keeps increasing with enactment of new laws creating new offences and penalties.

Court staff

Indian judiciary is one of the largest in the world and running such a mammoth justice delivery system calls for an efficient support staff. Enough care is not taken to ensure that qualified para-legal staff is appointed in the courts. Most states have only clerical staff who rise to become clerks-of-courts, or registrar. Between the judges and clerical staff, there is no recruitment of officials, thereby leaving a vacuum.

According to NCMS, number of staff in a given court is fixed by government circulars which are issued without taking into account the actual requirements. For instance, one bench clerk, one assistant bench clerk, one stenographer and two peons, are provided to a judicial officer, irrespective of whether the workload involves 500 or 5,000 files/cases. The increase in work load over the years has not resulted in corresponding increase in number of court staff. To put the issue in perspective, the National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG) says 10 per cent of the cases have been pending for over 10 years, 17 per cent between 5 and 10 years and the remaining 73 per cent have come up in the past 5 years.

There is also no policy in place regarding the ideal number of files to be handled by court staff for different courts at different levels. If the number of matters/cases increases, there is no provision for procuring additional staff. The problem gets compounded with the courts being crowded by new cases and the State not making provision for more staff commensurate with the workload. As of 2016, 41,775 staff positions for subordinate courts are lying vacant, hindering efficient functioning of the courts.

E-court Project

While paper work is fast becoming redundant and replaced by technology in many spheres, Indian judiciary is still heavily dependent on the same. It has been a decade since the Supreme Court launched electronic filing of petitions, and computerization in subordinate courts was started way back in 1997.

Upon completion, the e-court project — which aims to modernize and speed up justice delivery system by complete computerization of district courts — has the ability to fundamentally transform justice delivery and enhance the quality of access to justice to all. The progress in e-courts project has been painfully slow.

The computerization of courts was accelerated in 2007. A total of 13,000 district and subordinate courts were agreed to be computerized over two years at a cost of Rs. 441 crore. The period kept stretching and so did the cost. Eventually, the government committed to computerize 14,000 courts by 31st March, 2015, at a cost of Rs. 935 crore. This target was achieved with a completion rate of 94 per cent. In July 2015, the government launched Phase II of the computerization process spread over four years with a budget of Rs. 1,670 crore. However, during 2015 and 2016, Phase II did not achieve anything substantial. Now in 2017, the government aims to computerize 1,000 courts which the mission could not cover in Phase I.

A report released last year by Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, a New Delhi-based think-tank, said: “The predominant drivers of delay in the e-courts project are short-sighted policy formulation, inability to mitigate foreseen risks, flawed resource allocation, delays in funding approvals, no timely implementation, and lack of coordination in implementation.” The delays could have been prevented with coordination of activities within and across all stakeholder groups, said the report.

Corruption and Nepotism

With sitting and retired judges of the Supreme Court and the Delhi High Court as the audience, Justice Ruma Pal, a former judge of the Supreme Court, while delivering the fifth VM Tarkunde Memorial Lecture on 'An Independent Judiciary' in November 2011, pulled up the higher judiciary for what she referred to as the “seven sins” and eloquently called upon her fraternity to introspect in a manner few of her contemporaries have done.

The theme of her courageous speech was that independence of the judiciary and the judicial system ultimately depends on the personal integrity of each judge.

Highlighting the many inadequacies that plague the higher judiciary in the country, she listed, amongst others, nepotism as the seventh and final sin - wherein favours are sought and dispensed by some judges for gratification of varying manner. "What is required of a judge is a degree of aloofness and reclusiveness not only vis-a-vis litigants but also vis-a-vis lawyers. Litigants include the executive," she said.

"Injudicious conduct includes known examples such as judges using a guest house of a private company or a public sector undertaking for a holiday or accepting benefits like the allocation of land from the discretionary quota of a chief minister. I can only emphasise that again nothing destroys a judge's credibility more than a perception that he/she decides according to closeness to one of the parties to the litigation or what has come to be described in the corridors of courts as 'face value'.“

Lower Judiciary

Spanning hundreds of district courts and subordinate courts, the lower judiciary is the primary interface between the judicial system and the citizens of the country. In 2013, Transparency International reported that 36 per cent citizens had paid a bribe to the judiciary.

Comprehensive surveys have also been carried out to disaggregate the bribe recipients, which reveal the percentage of bribe paid to not just judges, but also lawyers and court officials, all in the name of speedy and favorable judgments! Corruption in lower judiciary manifests in many forms. There have been instances of Metropolitan Magistrates issuing bailable arrest warrants against individuals whose identities are unknown, in return for an inducement. Given the volume of cases pending in the courts; the number of judges across various states (per lakh of population); manipulation of a non-transparent justice system by court staff /officials; and political interference in appointments of judges in lower courts, the lower judiciary has unfortunately become synonymous with inefficiencies, delays and unpredictability. All these factors give rise in an ideal environment for middlemen and “fixers” to step in and exploit the litigants. Instances of corruption are reported in the media, but the negative coverage does not necessarily result in any action being taken. One of the reasons for the same is that under the existing laws, any person making an allegation of corruption or of any other grave nature against a sitting judge can be charged and punished for contempt of court.

Higher Judiciary

In the current framework, higher court judges are selected from the ranks of lower court judges and lawyers. The possibility of corrupt judges making it to higher courts always lurks as seniority is the primary ‘de facto’ criterion for promotion. On being appointed to higher courts, the judges can use their expansive “contempt of court” powers to hush up the allegations of corruption. The judiciary’s use of contempt of court proceedings against its detractors has often been blamed for suppressing a free and open debate on the subject of corruption in judiciary.

Several reform commissions, senior judges, and eminent jurists have from time to time laid out detailed proposals for weeding out corruption from the judicial system - right from the grassroots to the very top. Key suggestions include change in contempt of court and impeachment proceedings; enforcing integrity codes for judges and lawyers; extending the Right to Information Act to cover the judiciary; opening judicial vacancies to legal scholars; using alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms; and introduction of reliable technology. These reforms have been sluggish at best, with the judiciary and executive blaming each other for the delay.

Infrastructure Overhaul - Change in approach

Ideally speaking, an infrastructure overhaul of the judicial system is the way forward. The standard solution for dealing with the challenges has been to create more specialized courts and tribunals to minimize litigation and reduce the load on the higher judiciary. Several tribunals have been established under State and Central Government legislation. But rather than helping to clear the backlog, many tribunals have been reduced to just another institutional layer of litigation. Reason? Appeals against the tribunal verdicts are filed before the courts as a matter of routine. The courts have also been in the uncomfortable position of entertaining petitions on procedural issues in cases which are being heard by the tribunals.

Another solution, which is vigorously suggested from all quarters, is to increase the number of judges. At the 2016 Joint Conference of Chief Ministers of States and Chief Justices of High Courts, then Chief Justice of India TS Thakur famously appealed to the Central Government to increase the number of judges by 70,000, to reach the optimal benchmark of 50 judges per million of the population. But legal experts have questioned such estimates arguing that they are unachievable numbers which can seriously compromise judicial quality [Alok Prasanna Kumar, Senior Resident Fellow, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy].

Given the magnitude of the problem of delay and backlog, a third suggestion was made, that of using information and communication technology tools and modern case management systems to improve transparency.

As discussed earlier, in 2007, the Central Government launched e-court project in phases. In Phase I, hardware and software solutions were to be given to courts for fling cases, checking their status and issuance of certified copies of orders and judgments. In 2015, a study concluded that e-courts project did not produce the desired results and recommended further investment in infrastructure, hardware, Internet, amongst others. Fortunately, the second phase of e-projects aims to go beyond “computerization” and focuses on better workflow management through re-engineering processes like mobile applications etc. What, however, is lacking in this phase is digitization of substantial communication that takes place between judges, lawyers, court staff and the litigants.

As much as more judges and courts are needed, what is also needed is streamlining of procedure to hear cases on a continuous basis, sorting cases by the legal principle involved, and identifying the settled judicial opinion, so that lower courts do not waste precious time and resources delivering judgments which are bound to be overturned by a higher court. There is also talk of videography of court proceedings to be audited by a judicial audit body comprising former members of the higher judiciary, which could help in faster disposal.

In a nutshell, it is time to go beyond the traditional short term solutions and adopt unconventional solutions involving re-formulating and re-engineering judicial processes/procedures, including digital solutions, to rectify what is now being infamously referred to as “the legal logjam” in India.

Budgetary Allocations

The issue of budgetary allocations to judiciary and whether they do justice (pun intended) to the many ills plaguing the system is a sore point. Poor budgetary allocation over the years by successive governments is considered one of the prime reasons for the neglect of judiciary. The National Court Management Systems (NCMS) in its Policy and Action Plan released in 2012 by the then Chief Justice of India stated that judicial independence cannot be interpreted solely as a right to decide a matter without interference. “If judiciary is not independent resource-wise and in relation to funds, from the interference of the executive, judicial independence will become redundant and inconsequential,” it said.

The Union Budget for 2017-18 has earmarked Rs. 1,744.13 crore for the administration of justice, including justice delivery, legal reforms, development of infrastructural facilities and autonomous bodies associated with legal matters. Not surprisingly, legal experts have come down heavily on the allocation since it is less than one per cent of the total budget of Rs. 21.47 lakh crore. It is a no-brainer that the current budgetary allocation will not be sufficient to deal with the challenges posed by the backlog of nearly three crore cases languishing across the length and breadth of the country. In particular, the infrastructure facilities for Judiciary have witnessed an allocation of Rs 629.21 crore — a mere increase of Rs. 85.45 crore over the allocation of Rs. 543.76 crore in the revised budget for 2016-17.

While judicial reforms are being projected as the “top priority” of the Centre, the failure to substantially enhance the budgetary allocation for judiciary sends out a contradictory message vis- a -vis the seriousness to get rid of the problems of the judicial system. The larger issue remains the same - lack of independence of the judiciary in funding- while the legislature has steadily increased funding to itself, it sits in judgment on funding for other organs of the State!

Further, considering that judiciary is funded mostly by the states (apart from the Centrally-sponsored schemes of the Central Government),there has been no visible progress on estimating the extra case load and extra expenditure on the courts to be incurred on account of Central and State legislations, respectively. Against this backdrop, out of the special grant of Rs. 5,000 crore by the 13th Finance Commission for the period 2010-15 for improving judicial infrastructure and services, nearly 80 per cent of the grant was not utilized. A grim reminder of ground realities?

The moot question is whether enhanced budgetary allocations will enable the judiciary to dispense timely justice.

A 2004 research paper titled The Problem Of Court Congestion: Evidence From Indian Lower Courts (by Arnab K Hazra and Maja B Micevska) concluded that more judges, more courts, more computers alone may not do much to improve the efficiency of courts or access to justice. This can only be achieved by re-engineering, re-imagining court processes, widespread use of technology and reforms in substantive law.

Culture of Adjournments

It is natural to see delay in justice as a manpower or “human resources” issue which can be tackled by appointing more judges, an equally important aspect (albeit an invisible one) is the question of whether the culture of delay has been perpetuated by the judiciary itself. After all adjournments are acceptable in our judicial system! Adjournments not only encourage delaying tactics and waste judicial time, but also prevent effective case management. In some cases they have the effect of impoverishing the litigants. A recent study published in March this year by Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy conducted on Delhi High Court titled Inefficiency and Judicial Delay found that adjournments occur in alarming proportions in delayed cases and that 91 per cent of delayed cases involved at least one adjournment.

Ironically, the clamour for discouraging adjournment culture from within the judiciary is not a new one. Several Chief Justices of India have on various occasions called upon judges of all courts to discourage the practice of frequent adjournments sought by lawyers so that the disposal rate of cases can be increased. It has been suggested that the problem of adjournments can be dealt with by reducing government litigation; compulsory use of mediation and other alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, simplifying procedures, and use of technology, amongst others.

There are useful lessons to be learnt from judicial systems of other countries in the region. For instance, Singapore implemented similar reforms in the 1990s, leading to phenomenal results. About 95 per cent of civil and 99 per cent of criminal cases were disposed of in 1999; and the average length of commercial cases fell from nearly six years in the 1980s to 1.25 years in 2000!

The aim is to clear the judicial backlog within a stipulated time frame. But is this possible in the current scenario? Implementing the above-mentioned changes will undoubtedly pose their own set of challenges. To begin with, the narrative around judicial delays must change. It is about time we stopped seeing the issue of delay in courts through the narrow prism of it being manpower and/or infrastructure issue only. There is another underlying concern that of allowing a culture that has made delays acceptable to us as a society. It is this very culture which impacts our global business rankings as well as denies justice to the common man who approaches the court. The onus is not just on the Bar. Litigants too need to understand and ensure that adjournments are not sought on shallow/frivolous grounds.

The Push to Reform

Every three years, a new Law Commission is appointed to work on legal reforms in tandem with the Ministry of Law and Justice. Over the years, 20 Law Commissions have given a plethora of suggestions to reform the judicial system. These range from constituting more number of benches, increasing the judges ratio per million of the population, to computerizing the entire judicial process, and bunching of similar cases to conduct their hearing under one bench, to name a few. Reforming the Indian judicial system is a huge task given the size of the judiciary. In addition to the need for addressing the issues of adequate court rooms, infrastructure, and adequate number of judges, some particular problem areas require immediate action, for the time of paying lip service has long passed.

To begin with, the plethora of laws, rules, orders and administrative instructions are not entirely consistent with many laws contradicting each other. While some areas are over-regulated, resulting in large number of court, tribunal and quasi-judicial cases, there are lacunas/gaps in some other laws resulting in filing of frivolous cases. To take one example, the property rights and the related tenancy rights are ill-defined to such an extent that a large volume of litigation surrounding property matters is generated. Doing away with contradictory laws and re-looking at poorly defined ones is thus imperative.

Next comes the issue of legal proceedings being cumbersome and long-drawn, which slows down the rate of disposal of cases. In any given case requiring certain number of hearings, there are some adjournments on inconsequential grounds; while on some hearing dates, the judge is absent, thereby reducing the number of effective hearings in the case. Additionally, the gap between the dates of hearing may extend to several months increasing the pendency of cases. The wasteful culture of adjournments has led to suggestions being made to the government to examine the provisions of not allowing more than one adjournment for each party and enforce it.

Thirdly, while there is a statutory limitation of time for filing a suit in the court of law, there is no such limitation of time for finalizing the cases by the courts. Some countries have introduced legislations for disposal of cases in less than the specified number of days. The stakeholders and policymakers are now pitching for a framework in India wherein time limits are prescribed for taking decisions by the courts. “There is a need to make time barring provisions in all civil and criminal laws to enact the judgment by each and every court like taluka & district court, session’s district & judge court (appeal), high court and the Supreme Court,” said a note prepared by the Ministry of Commerce.

Another area for immediate attention is that of district courts having to deal with a broad range of civil, criminal and commercial cases and there being no specialized fast track commercial courts. This puts tremendous pressure on the lower judiciary as it is not in a position to expedite the enforcement process and ensure a definite and predictable time frame for rehabilitation and liquidation process. Various groups and stakeholders are, therefore, recommending setting up of special commercial courts to hear and decide commercial lawsuits similar to those for tax and some employment matters.

The good news is that since government litigation constitutes nearly 46 per cent of all the court cases, the Central Government is aiming to usher in the judicial reforms and a National Litigation Policy on a priority under the supervision and aegis of Ministry of Law and Justice.

Undoubtedly, it’s a tall order to achieve. Chief Justice of India Jagdish Singh Khehar recently elaborated on the aspirational nature of judicial reforms. “While Justice is inspirational, judicial reforms are only aspirational,” he said.

Speaking at Rashtrapati Bhawan on Redundant Laws in February this year, the CJI also shed light on recent judicial appointments and assured that it was “in advanced stage of finalisation”. The recommendations made for appointment of judges to the Supreme Court has come through; and recommendations have also been made for filling up eight vacancies of Chief Justices of High Courts, he pointed out.

In 2015, the apex court was accused of scuttling the judicial reform move by striking down a law giving the government a bigger role in the appointment of top judges, as being harmful to judicial independence. In 2017, judicial reforms and the controversy over judicial appointments seem to be simmering at the highest levels of both the Judiciary and the government. Will the push to make judicial justice quick and just succeed?

Part 2 of this article will focus on the emergence of Alternate Dispute Resolution (ADR) System as an alternative, the benefits and the challenges thereof…

Richa has over 10 years of experience in legal writing and editing. She completed her Masters (LLM) in Commercial Laws from the London School of Economics and Political Science and is a qualified Solicitor in England and Wales. Richa started her career with SNG & Partners, an established pan India banking law firm. She went on to pursue her keen interest in legal research and writing as the Senior Legal Editor with LexisNexis India. Her subsequent stint as the Consulting Editor of Lex Witness, India’s first Magazine on Legal and Corporate Affairs, honed her analytical understanding of legal subjects. She was also involved with setting up of Live Law. A ‘hands-on’ mother of two young children, Richa is currently based with her family in Singapore.

Richa has over 10 years of experience in legal writing and editing. She completed her Masters (LLM) in Commercial Laws from the London School of Economics and Political Science and is a qualified Solicitor in England and Wales. Richa started her career with SNG & Partners, an established pan India banking law firm. She went on to pursue her keen interest in legal research and writing as the Senior Legal Editor with LexisNexis India. Her subsequent stint as the Consulting Editor of Lex Witness, India’s first Magazine on Legal and Corporate Affairs, honed her analytical understanding of legal subjects. She was also involved with setting up of Live Law. A ‘hands-on’ mother of two young children, Richa is currently based with her family in Singapore.

Image from here