Sec 66A- An exaggeration of your rights end where my nose begins

Akanksha Prakash

10 Feb 2015 6:00 PM IST

The number of social media users in urban India would reach 302 million by Dec 2014 registering a Y-o-Y growth of 32% last year, according to a report ‘Internet in India 2014’, jointly published by the Internet and Mobile Association of India (IMAI) and IMRB International. According to this survey, for 93% of the respondents in urban India, the primary use of internet is Search, followed by Online Communication and Social Networking. With such an enormous rise in the social media-savvy population, it is not unusual to predict a sharp increase in the rate of cyber crimes in the country which simultaneously breeds the dire need to come up with a breakthrough legislation in order to punish and prevent criminals in social media. Uptill 2008, sending offensive messages, creating fake profiles, e-mail account hacking, cyber pornography or web defacement for that matter were committed and taken casually, leaving the victim terrorised and helpless. Then, Section 66A came to the rescue with a subsequent amendment in IT Act of 2000 and has turned lately into the harbinger of a multitude of legal logjams which hinder the smooth excercise of our fundamental rights upheld in Part III of our Constitution.

Article 19 of the constitution of India guarantees certain rights regarding freedom of speech and expression to an Indian citizen. However, in 19(2) it has been held that this freedom may be restricted in the interest of the sovereignty and integrity of India, security of state, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency, morality or in relation to contempt of court, defamation or inticement to an offence. In yet another sub-article i.e. 19(3), it is stated that the said clause shall not affect the operation of any existing law and only reasonable restrictions can be imposed on it by subsequent legislation. In the absence of a lucid interpretation of this “reasonable restriction” which is to be based on an intelligible differentia, many legislations have been passed imposing rather preposterous restrictions on the same. One such instance is that of Sec. 66A introduced on 27th Oct,2009 by amending IT Act, 2000 which has been adopted from a similar provision in the United Kingdom`s Communication Act, 2003. However, the Queen`s Bench Division of the High Court has read down this provision in 2012, making the UK more tolerant of free speech online.

Section 66A of IT Amendment Act 2008 which deals with online offensive content incorporates punishment which is imprisonment upto 3 years and fine. In keeping with the provisions in this section, any person who sends by means of a computer resource or communication device-

- a) any information that is grossly offensive or has menacing character; or

- b) any information which he knows to be false, but for the purpose of causing annoyance, inconvenience, danger, obstruction, insult, injury, criminal intimidation, enmity, hatred or ill will, persistently by making use of such computer resource or a communication device,

- c) any electronic mail or electronic mail message for the purpose of causing annoyance or inconvenience or to deceive or to mislead the addressee or recipient about the origin of such messages, shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to three years and with fine.

Explanation: For the purposes of this section, terms "electronic mail" and "electronic mail message" means a message or information created or transmitted or received on a computer, computer system, computer resource or communication device including attachments in text, images, audio, video and any other electronic record, which may be transmitted with the message.

The offence under 66A being cognizable, police authorities were initially empowered to arrest or investigate without warrants, based on charges brought under the Section. This resulted in a string of highly publicized arrests of citizens for posting objectionable content online, where the ‘objectionable’ contents were more often than not, dissenting political opinions. The instances cover States from almost every nook and corner of India, be it the arrest of PUCL activist Jaya Vindhayal for the facebook comments against Tamil Nadu governor K. Rosaiah in Andhra Pradesh or the arrest of two innocent girls in Mumbai over the contemptous facebook posts and comments on Nov 18 declaring that Mumbai shut down because of fear and not out of respect for Balasaheb Thackeray who, apparently died on Nov 17 or of the businessman Ravi Srinivasan by the Pondicherry Govt. for making allegations of corruption against P. Chidambaram`s son and the widely highlighted incident of the arrest of Chemistry professor from Jadavpur University in West Bengal for posting a cartoon poking fun at CM Mamata Banerjee on social networking sites. Such arbitrary arrests which clearly tampered the fundamental rights of Indian citizens manifest the need for educating the law enforcement agencies and its personnel i.e. an effective implementation of the newly framed law. Meanwhile, after such condemnable incidents of misuse of the act, the Indian Govt. issued guidelines which states a prior approval from an officer of DCP level in the rural areas and of IG level in the metros will have to be taken before registering complaints under Section 66(A), as reported by The Hindu.

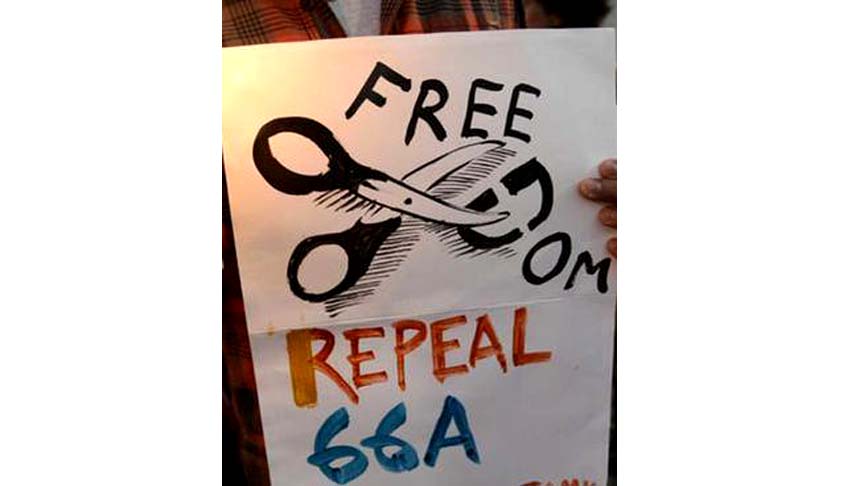

In the wake of such appaling Facebook arrests, a 21 year old girl from Delhi, Shreya Singhal filed a Public Interest Litigation in the Supreme Court declaring Sec 66A to be `ultra vires` the constitution. This piece of drafting, which criminalizes causing annoyance or inconvenience online had already been criticized for being too sweeping in nature. This case was not only taken up by former Chief Justice Altamas Kabir court, he also wondered why nobody had so far challenged this particular provision of the IT Act. The main plea in Shreya Singhal v. Union of India was to issue guidelines so that offences concerned with free speech and expression are treated as non-cognizable under criminal law, meaning that police powers are brought under safeguards on areas such as making arrests without warrant as well as the power to investigate. In yet another petition, Mouthshut.com v. Union of India the Information Technology (Intermediaries Guidelines) Rules, 2011 were challenged which effectively creates a notice and takes down regime for third party/user content that intermediaries host. Originally, the IT Act was meant to create a safe harbour for intermediaries, to shield them from liability for third party content. However this safe harbour is subject to the intermediaries meeting a `due diligence` standard-the rules which were meant to explain what this standard meant, have instead created a whole liability system surrounding contexts in which intermediaries are given notice of objectionable content and do not take it down within specified time. Thus, the petition argues that as delegated legislation, the rules are not only unconstitutional but also go well beyond the scope permitted by the IT Act. As a mark of protest against Section 66A of the Act, to display strong dissent against the arrest of Aseem Trivedi and vindicate the hunger strike being excercised by Aseem Trivedi and Alok Dixit, Anonymous, the infamous hactivist group hacked and defaced the website of BSNL in Dec 2012. Their persistent claim for scrapping out this section created a massive furrore throughout the country which actually advanced the urge for an absolute execration of Internet Censorship all over the country.

With the enactment of the IT Act in the year 2000 and its subsequent overhauling in 2008, it can be deduced per se that several attempts have been made hitherto to galvanise the scope and applicability of the aforementioned Act. Consequently, major provisions of The Indian Penal Code 1860, The Indian Evidence Act 1872, The Bankers` Book Evidence Evidence Act 1891, Code of Criminal Procedure 1973 were also amended to cater to the needs of effective execution of IT Act. But despite such massive interpretations, some obstrusive factors augment the demand for further clarifications on issues like jurisdiction, preservation of evidence etc which have not been deliberated upon well by the legislators. Territorial Jurisdiction is one such issue. Jurisdiction has been mentioned in Sections 46, 48, 57 and 61 in context of the adjudication process and the appellate procedure connected with and again in Section 80 and as part of the police officers' powers to enter, search a public place for a cyber crime etc. Since cyber crimes are basically computer-based crimes and therefore if the mail of someone is hacked in one place by accused sitting far in another state, determination of concerned authority who will take cognizance is difficult. The most unfortunate part lies therein that the investigators generally try to avoid accepting such complaints on the grounds of jurisdiction. With respect to the cyber crimes committed internationally and the altercations arising on their jurisdiction, former Telecom and IT Minister Mr. Kapil Sibal said, "If there is a cyber space violation and the subject matter is India because it impacts India, then India should have jurisdiction. For example, if I have an embassy in New York, then anything that happens in that embassy is Indian territory and there applies Indian Law. If the impact of such a violation is on India, then Indian courts must have the jurisdiction.” That should apply across the world," former Telecom and IT Minister Mr. Kapil Sibal said. Since the cyber crime is geography-agnostic, borderless, territory-free and generally spread over territories of several jurisdiction, it is quintessential to determine the solution to counter this. Another lacuna lies with the preservation of evidence. One can`t be oblivious of the fact that while filing cases under this Act, there lie chances to destroy the necessary easily as evidences may lie in some system like the intermediaries' computers or sometimes in the opponent's computer system too.

A panel was set up to review the applicability of Section 66A of the Information Technology Act by the Centre. However, in a recent press release by the Supreme Court, a bench of Judges J Chelameswar and Rohinton F Nariman made it clear to the Centre that it would not wait till the panel decides on the applicability of Section 66A and propose amendments, if any. “We have to judge this statute and the provisions therein as they stand today. We cannot wait for an amendment or the new guidelines that you may propose tomorrow”, said the bench. The key question to be probed is whether the individual cases booked under this provision are isolated instances of abuse or the section itself is flawed. But surely it cannot be a legitimate legislative objective for a democratic society to restrict freedom of speech in order to prevent annoyance, ill-will, insult or inconvenience. Apparently, it is disingenuous for the govt. to criminalise this duty of criticising political parties or persons for their acts of omissions and commissions in order to avail the prerogative of a better governance because as a matter of fact, that`s how democracy evolves for the better!

Akanksha Prakash is a Second year Student at Government Law College, Mumbai and a Student Reporter at Live Law