- Home

- /

- Cover Story

- /

- Kailash Satyarthi’s legal...

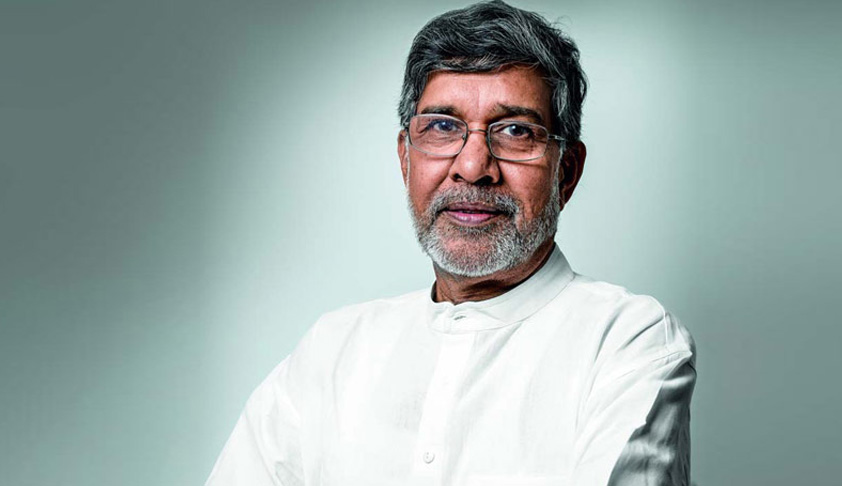

Kailash Satyarthi’s legal struggles: PILs facilitating the cause

Apoorva Mandhani

21 Oct 2014 4:13 PM IST

Kailash Satyarthi, the joint winner of this year’s Nobel Peace Prize, gleams with honesty when he says that “children are his religion”. Satyarthi considers this a victory of not just a man, but the entire cause, the cause that he has been fighting for, with his heart and soul for more than 3 decades.The electrical engineer started off with teaching at a college in Bhopal,...

Tags

Bachpan Bachao Andolan (BBA)Bachpan Bachao Andolan v. Union of India and othersBandhua Mukti Morcha (BLLF)Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act 1976Cheif Justice A P ShahChild Labour ActJuvenile Justice ActKailash Satyarthi’s legal strugglesNobel Peace Prize SatyarthiPILRight of ChildrenSupreme Court on Children's Rights

Next Story