Conversation with Professor George H Gadbois Jr, a distinguished scholar of Indian law and judicial behaviour

Raghul Sudheesh

16 Aug 2013 1:05 PM IST

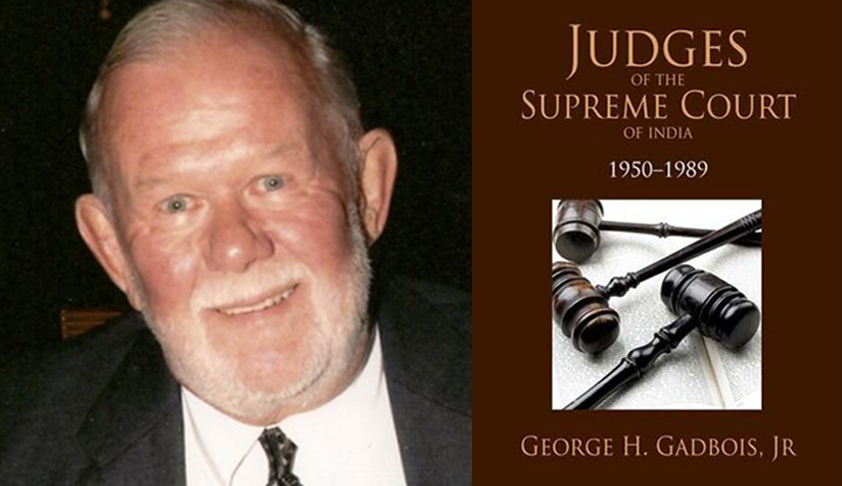

George H Gadbois Jr. is Professor Emeritus of Political Science, University of Kentucky, USA. His research over half a century dealing with the Supreme Court of India has appeared in various publications since the 1960s. Gadbois is the author of the book ‘Judges of the Supreme Court of India: 1950-1989’, which essays the background and life of the first ninety three judges who served the Supreme Court from 1950 to 1989. He has also authored many other articles and book chapters dealing with Indian courts, judges, judicial behaviour and judicial policy-making, dating back to 1963.

In this interesting conversation with Live Law, Gadbois Jr. talks about the origin of the book, Indian Judiciary, some of the best Chief Justices and Judges, people who refused to accept Supreme Court Judgeship, and much more...

Live Law: Can you tell us about the birth of the book ‘Judges of the Supreme Court’? Will there be a second part to the book?

George H Gadbois: I have been interested in your SCI (Supreme Court of India) judges for over half a century, since my first visit to India in academic year 1962-63, when I was a graduate student at Duke University. Affiliated with the Indian Law Institute, I was fortunate to be mentored by Dr. A T Markose, its director at that time. I rather quickly learned that Indians make good judges. One result of that year was "Indian Supreme Court Judges: A Portrait" (Law & Society Review, 1968-69). No, I am not planning a second book which would cover the post-1989 years. At age 77, it's time to fold the tent and enjoy reading the works of today's generation.

Live Law: What all hurdles did you face in the compilation of the book ‘Judges of the Supreme Court’?

George H Gadbois: There were no hurdles in collecting the biographical materials. Before meeting each of the judges I scoured every available source of information about them, and read something they had written - recall that I did the interviewing in 1983 and 1988 before the SCI had a website. The judges quickly saw that I had done my homework and was well-informed about the Court. And all were pleased that I was interested in their backgrounds. Most had never been interviewed. I requested 45 minutes of their time. Very often the interviews lasted much longer and some were accompanied not just by tea and snacks, but by lunch or dinner. Most clearly enjoyed the experience, and were quite forthcoming. Writing up the interview materials was another matter, much more difficult than I had anticipated. It's not easy writing about named individuals.

Live Law: Recently, Live Law investigation has revealed that Justice U L Bhat was not elevated to the Supreme Court for being ‘irreverent’ to his seniors. What do you think is the actual reason for Justice M N Venkatachaliah not elevating Justice U L Bhat?

George H Gadbois: I find Justice Bhat's account difficult to believe. I met Justice Venkatachaliah and found him to be a consummate gentleman.

[Editors Note: Live Law spoke to Justice M N Venkatachaliah about the allegations raised by Justice U L Bhat and he has confirmed that, if Justice U L Bhat has said so, it might have happened. However he does not remember the particular incident as it happened almost 20 years ago]

Live Law: Did you gather any information regarding the Justice M N Venkatachaliah Court or the first collegium consisting of Justices M N Venkatachaliah, Ratnavel Pandian and A M Ahmadi?

George H Gadbois: No, I returned to the University of Kentucky in early 1989, well before the collegium era began. But by confining the recruitment plateau almost entirely to rather elderly High Court Chief Justices, the role of merit is further diluted.

Live Law: Recently Gujarat High Court Chief Justice Bhaskara Bhattacharya has alleged that he was not elevated to the Supreme Court for opposing Justice Altamas Kabir’s sister’s elevation to the Calcutta High Court. Do you remember any such instance in the past or during your course of study?

George H Gadbois: I know nothing about the Justice Bhattacharya matter. Earlier there was an incident when a particular High Court judge was being considered for appointment to the Court. His appointment was resisted by a senior Supreme Court associate judge whose objection was that the judge had threatened to shoot his dogs! The man was not appointed.

Live Law: Your book says Justice V S Malimath refused to accept Supreme Court Judgeship probably because he would become junior to his colleagues Justice E S Venkatramaiha and K Jagannatha Shetty. Justice M N Venkatachaliah who was five years junior to Justice V S Malimath was appointed to the Supreme Court without even being a High Court Chief Justice. Did you notice this fact? Do you think this was the actual reason behind his refusal?

George H Gadbois: During the first 40 years, less than half the appointees came from the ranks of High Court Chief Justices. CJI Pathak had a high opinion of Justice M N Venkatachaliah, correctly so in my view, and reached down to third in seniority at Karnataka to bring him up to Delhi. Justice V S Malimath was also senior, though by less than four months, to Justices E S Venkataramiah and K Jagannatha Shetty. If Justice Malimath declined an invitation to the SCI because a junior was appointed ahead of him, he wasn't the first or last to do so.

Live Law: You have studied the system of appointment of judges before the Judges case and after the Judges case. Which is better according to your opinion?

George H Gadbois: Only the first judges' decision occurred during the years of my book. It affected mainly the high court appointments. It had a very small effect on SCI appointments. More significant during the 1980s was Shiv Shankar's role in appointments. Both as law minister and when he held other portfolios, he was a judge-maker with his own selection criteria, and made life difficult for chief justices.

Live Law: Do you know any country other than India where Judges appoint Judges?

George H Gadbois: I am not well-informed about courts in many other countries. Judges play some role in selecting their colleagues in some countries, but, to my knowledge, nowhere else do they have as much power to do so as in India.

Live Law: Who according to you is the best Chief Justice of India and why?

George H Gadbois: This is a very difficult question. But I'd say that Justice S R Das was the best in the 1950s. He made some excellent choices, most of whom were relatively young men. Six (Justices P B Gajendragadkar, A K Sarkar, K Subba Rao, K N Wanchoo, M Hidayatullah, and J C Shah) of the ten appointed during his years (1956-1959) later became chief justices. He also played a major role in promoting good relations among his the judges. During the 1960s, my choice is Justice M Hidayatullah (1968-1970). A brilliant man and a real leader of the court, he enjoyed the respect of his colleagues, and the bar. For the 1970s, my vote goes to Justice S M Sikri (1971-1973). This will surprise some, but he presided during a very transformative and difficult period. The executive in 1971 reclaimed the power it clearly had to select judges, and all nine of the appointees during his reign were chosen by the government. Justice Sikri did have a veto, and used it, but for the most part he and his colleagues found the executive's choices to be satisfactory ones. And they were - they included Justices H R Khanna, K K Mathew, A K Mukherjea, and Y V Chandrachud. For the 1980s, my choice is Justice Y V Chandrachud (1978-1985). His tenure embraced two presidents, four prime ministers, five law ministers, the first judges case, and the new era of “activism" led by Justices V R Krishna Iyer and P N Bhagwati. The court was fractured probably more than ever before. Under all these circumstances, his tenure was a difficult period in the Court's life.

Live Law: Who according to you is the best Judge India has ever seen and why?

George H Gadbois: This too is a very difficult question. For the 1950s, the choice is relatively easy. This is Justice Vivian Bose. A soft-spoken and shy man, he was the most outspoken civil libertarian during the first decade (see my "Indian Judicial Behaviour," EPW, 1970). During his many years at the Nagpur High Court, he was a freedom fighter from the bench, and after arriving in Delhi he was no less a defender of civil liberties. During the 1960s, my vote is for Justice J C Shah. He served the entire decade, and he outworked all of his colleagues, usually dictating his opinions immediately after the hearings concluded. He is remembered by most for his Shah Commission after the Emergency, and his contributions during his years on the Court have been overlooked. For the 1980s, the choice is between Justices P N Bhagwati and V R Krishna Iyer. It's my view that Justice Krishna Iyer was the best of the two. Impeccably honest, a game changer in that he, more than Justice Bhagwati, spoke effectively for the poor. Though Justice Bhagwati fans may disagree, Krishna Iyer was, I believe, the founder of Public Interest Litigation and the liberal expansion of locus standi. Choosing just one from the 1980s is almost impossible. Justices Chandrachud and Bhagwati served well into the 1980s, and the latter in particular would likely receive most votes in a poll. Overlooked have been the contributions of Justices O. Chinnappa Reddy and D P Madon.

Live Law: Can you tell us about the people who refused to accept Supreme Court Judgeship, particularly lawyers and the reasons for it?

George H Gadbois: According to chief justices, at least eight senior advocates (the number is probably larger) declined invitations to become SC judges. These were H M Seervai (1957 and again in the early 1960s), Lal Narayan Sinha (1958 and the again in early 1960s), Nani Palkhivala (1961 and again a few years later), S V Gupte (1964), Fali Nariman (1979 and perhaps again later), K K Venogopal (1979), S N Kacker (1979), and K Parasaran (1979 and perhaps later). Had they accepted, and assuming the seniority convention, Seervai would have been CJI for nearly five years. Palkhivala, who was only 41 in 1961, would have been CJI for 14 years (1971-1985), and Fali Nariman, if appointed in 1979 would have been chief for four years, assuming, of course the continuation of the seniority convention.

The major reason for senior advocates declining invitation was money. As late as the mid-1980s, Rs. 5000 per month was the salary of the Chief Justice and Rs. 4000 for the associate judges, unchanged since 1950. One of the senior advocates told me in 1983 that "a junior of four years standing" at the bar makes as much as a Supreme Court judge. The income of prominent advocates was increasing in leaps and bounds, and far exceeded the salaries of the SCI's judges. Each pair of judges shared one car, while some senior advocates had two. Other reasons were the low pensions and the prohibition of practice anywhere in the country after retirement.

At least as many High Court judges declined invitations. An abbreviated list includes M C Chagla, Dr. P V Rajamannar, and P B Chakravartti, Chief Justices of Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta respectively. Others were Satish Chandra (Chief Justice at Allahabad), M M Ismail (Chief Justice at Madras), and V S Malimath, the Chief Justice in Kerala. Some were reluctant to leave the glamour of a prestigious high court chief justiceship to become the most junior judge of the SCI. Some declined at least in part because a junior was already in Delhi.

Live Law: You mentioned to me once that refusal of judgeship by some eminent lawyers cheapened the Court. Can you elaborate this statement?

George H Gadbois: Yes, I do believe that the refusal of leading advocates to accept an appointment cheapens and diminishes the Court. Leading advocates were happy to get rich practicing before the Court, but had no interest in becoming judges themselves. In the United Kingdom, nine of every ten barristers accept offered judgeships. In becoming judges they are giving back to the profession. In India, a lucrative private practice trumps the dignity, honour, security, and prestige that comes with a judgeship and denies the nation and the Court of able judges.

Live Law: Justice A N Ray granted you the only interview he ever gave to anyone. How was this possible?

George H Gadbois: When I first wrote to Justice A N Ray requesting an interview, I included a couple of articles I had published earlier. This enabled him to see that I was rather well-informed about him and the Court. He responded that he would be pleased to spend some time with me. The first half hour was a little tense, but during the last 2 1/2 hours both of us were comfortable and relaxed. It was an excellent interview. Mangos, other snacks, and tea were served, and we enjoyed each other's company. We stayed in touch over the years. That interview was one of my first, and I regret that I didn't take up his invitation to return to Calcutta for more conversations.

Live Law: In your book, the judges are broadly divided into two ‘generations’ (from 1950 to 1970 and from 1970 to 1989). You indicate that the second generation of Indians were being more “Indian” in the outlook they brought to Delhi than the first generation. You attribute this difference to the fact that the latter were mostly educated in the West. Is there anything more to this?

George H Gadbois: No, there really isn't much more. The first generation largely because their rather privileged backgrounds and education in England meant that they were more cosmopolitan, and also more detached from the "real India" than the post-1970 judges. Particularly with the arrival of Justices P N Bhagwati and V R Krishna Iyer on the same day in 1973, the Court commenced to deal with the real issues of India, particularly the plight of the downtrodden, the largest segment of the population.

Live Law: Critics argue that you have been polite in your book to judges and there is hardly any criticism on them. How do you take this?

George H Gadbois: Yes, there have been some objections that I was too kind to the judges. The reviews have ranged from the book being a "masterpiece" to "disappointing." I had no intention of evaluating the judges. It would have been absurdly presumptuous on my part to attempt to evaluate or critically assess the contributions of 93 judges. Is there anyone in India who could do that? My intent was to provide descriptive biographical essays for them, and provide some information about how and why they had been selected. The interviews can fairly be labelled "soft." The book was written for a broad audience. It's not a law book and not a political science book, and it's bereft of unnecessary jargon. Had I not written it, there was no one else on the horizon who would have or could have written it. Had I not stepped up, a lot of history of the Court's first 40 years would have been lost.

George H Gadbois: Yes, there have been some objections that I was too kind to the judges. The reviews have ranged from the book being a "masterpiece" to "disappointing." I had no intention of evaluating the judges. It would have been absurdly presumptuous on my part to attempt to evaluate or critically assess the contributions of 93 judges. Is there anyone in India who could do that? My intent was to provide descriptive biographical essays for them, and provide some information about how and why they had been selected. The interviews can fairly be labelled "soft." The book was written for a broad audience. It's not a law book and not a political science book, and it's bereft of unnecessary jargon. Had I not written it, there was no one else on the horizon who would have or could have written it. Had I not stepped up, a lot of history of the Court's first 40 years would have been lost.

Live Law: Do you think we need more direct appointments to the Supreme Court from the Bar and the Academia?

George H Gadbois: I do. Today it seems that High Court Chief Justices feel that they own the Court. Sadly, during my  years, leaders of the bar were happy to exploit the Court for riches, but refuse to serve on it. And there has been a sea change in the quality of some of the newer law schools during the past generation. Law has gone from one's last choice to a very promising and lucrative career. There must be brilliant academics whose presence would grace the Court. There is only a minimal correlation between promotions largely on the basis of seniority and merit. To say that appointments have been on the basis of merit is silly and just not true, unless merit is defined not by the just the usual indicators, but also by age, geographic region, caste, religion, and high court seniority.

years, leaders of the bar were happy to exploit the Court for riches, but refuse to serve on it. And there has been a sea change in the quality of some of the newer law schools during the past generation. Law has gone from one's last choice to a very promising and lucrative career. There must be brilliant academics whose presence would grace the Court. There is only a minimal correlation between promotions largely on the basis of seniority and merit. To say that appointments have been on the basis of merit is silly and just not true, unless merit is defined not by the just the usual indicators, but also by age, geographic region, caste, religion, and high court seniority.

Live Law: You gathered so much information before the advent of the Right to Information Act. How was this possible?

George H Gadbois: I experienced no difficulties. I did my homework before meeting the judges, and literally all were cooperative, some more than others, of course the interviews focused on their backgrounds but often morphed into conversations about many other matters. I learned a great deal. It was a privilege to get to know them. On several occasions, I left an interview thinking that India was getting better judges that it deserved, given the low salaries and working conditions.

Live Law: Have you studied about capital sentencing in India? Even the Supreme Court admits it is judge centric. What do you think?

George H Gadbois: No, I know little about that matter in India.

Live Law: What is the biggest problem plaguing Indian judiciary? Is there corruption in judiciary in India according to you?

George H Gadbois: Everybody talks about the arrears. I wonder if there is another court in the world with some 50,000 cases pending. My focus has been on the judges, and it is impossible for me to believe that narrowing the field of selection to only high court chief justices is a good idea. There must be brilliant judges on the high courts who will never get to the SCI because they were appointed too late to become chief justices of their high courts. I realize that seniority is part of Indian culture, but an argument can be made that making it the primary criterion does not serve the nation well. I'm going to pass on the corruption query. There was little talk of it in the 1980s, but it's working its way up to the front burner now.

Live Law: What are your future plans? Do you plan to conduct more research on Indian Judiciary or Courts?

George H Gadbois: I may do a few more small things, but nothing close to as large a project as the book. But that is subject to change!

Live Law: How was your experience in India?

George H Gadbois: You asked about my overall experience in India. I have loved being over there. I've spent four academic years there (1962-63, 1969-70, 1982-83, and all of 1988). Plus several shorter visits. I'm fortunate that I had these opportunities. I actually see the book in part as a token of my thanks for the privilege of spending parts of my life in India.