- Home

- /

- Cover Story

- /

- Bhopal and Section 377 – Two...

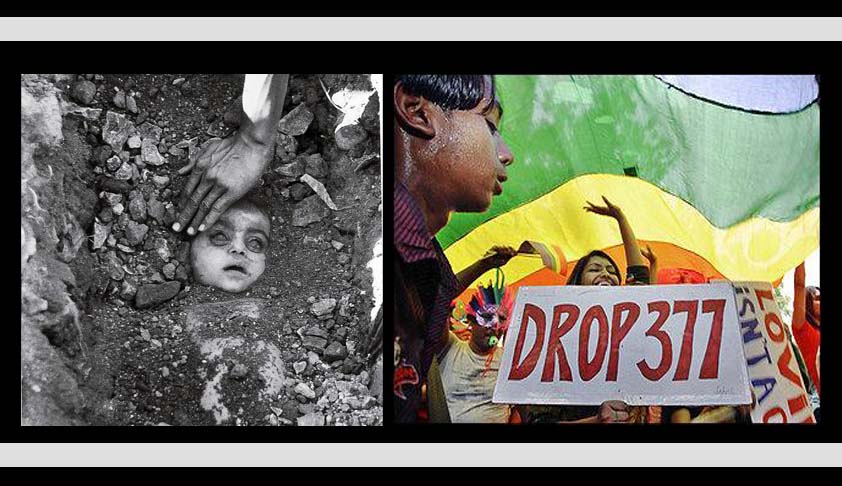

Bhopal and Section 377 – Two Curative cases compared

LiveLaw Research Team

3 Feb 2016 1:51 PM IST

On May 11, 2011, a five-Judge Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court had given ruling on the curative petition filed by the CBI against the Court’s judgment in Keshub Mahindra v. State of Madhya Pradesh on 13 September 1996.The CBI’s plea was that in 1996, the Court had erroneously ignored material which would have made, prima facie, an offence chargeable under section 304 (Part II)...

Next Story